Absolute Power

Asked about the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, Mohammed bin Salman said, “If that’s the way we did things, Khashoggi would not even be among the top 1,000 people on the list.”

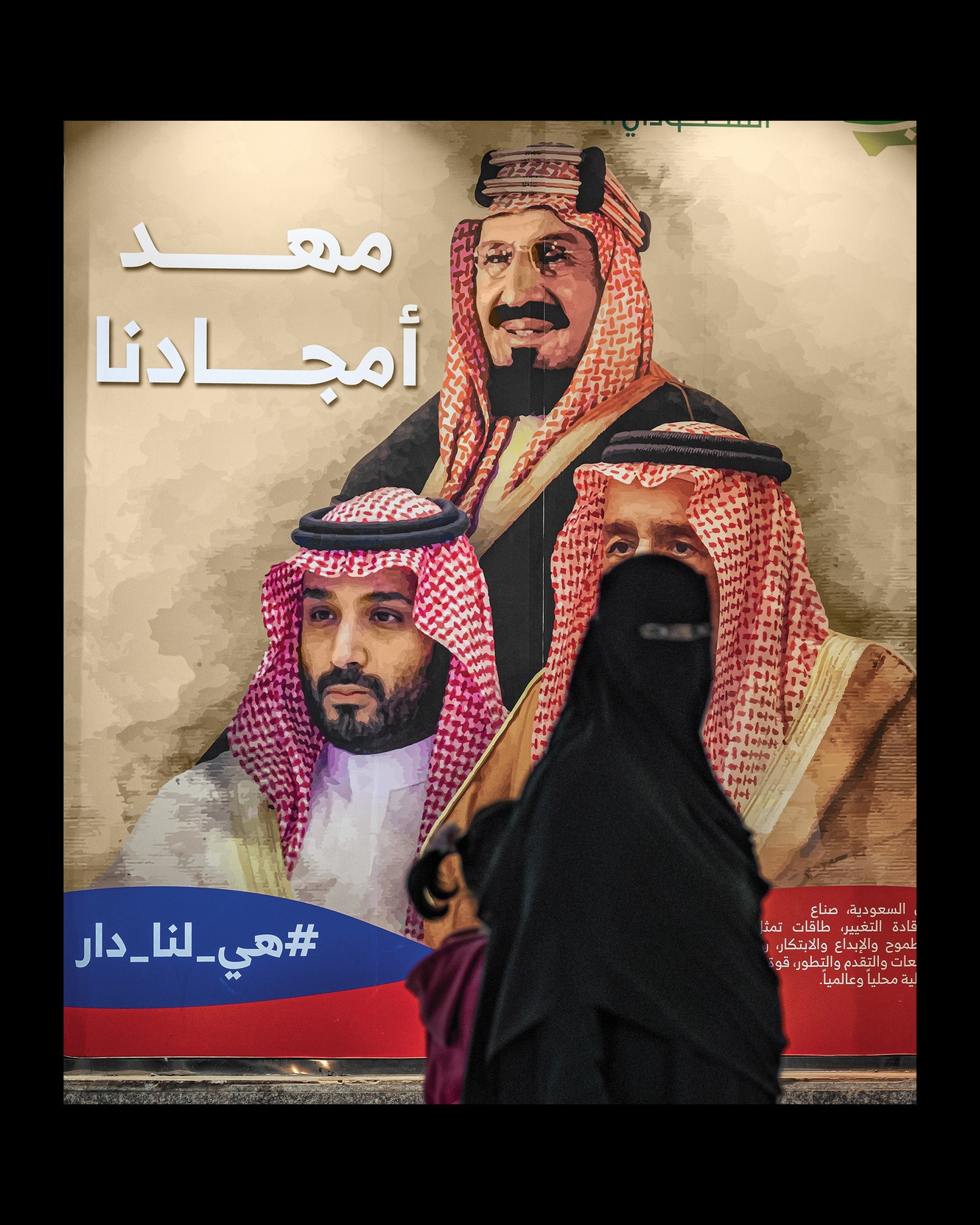

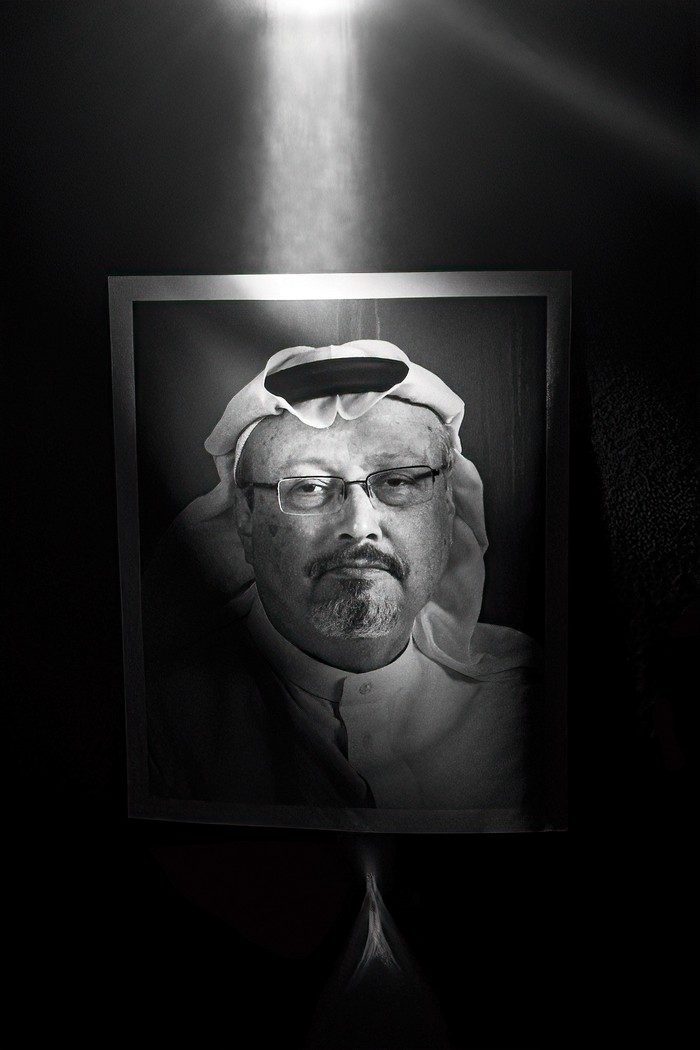

Mohammed bin Salman, the crown prince of Saudi Arabia, is 36 years old and has led his country for almost five years. His father, the 86-year-old King Salman, has rarely been seen in public since 2019, and even MBS—as he is universally known—has faced the world only a few times since the pandemic began. Once, he was ubiquitous, on a never-ending publicity tour to promote his plan to modernize his father’s kingdom. But soon after the murder of the Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018, MBS curtailed his travel. His last interview with non-Saudi press was more than two years ago. The CIA concluded that he had ordered Khashoggi’s murder, and Saudi Arabia’s own prosecutors found that it had been conducted by some of the crown prince’s closest aides. They are thought to have dismembered Khashoggi and disintegrated his corpse.

MBS had already developed a reputation for ruthlessness. In 2017, he rounded up hundreds of members of his own family and other wealthy Saudis and imprisoned them in Riyadh’s Ritz-Carlton hotel on informal charges of corruption. The Khashoggi murder fixed a view of the crown prince as brutish, thin-skinned, and psychopathic. Among those who share a dark appraisal of MBS is President Joe Biden, who has so far refused to speak with him. Many in Washington and other Western capitals hope his rise to the throne might still be averted.

Enjoy a year of unlimited access to The Atlantic—including every story on our site and app, subscriber newsletters, and more.

Become a SubscriberBut within the kingdom, MBS’s succession is understood as inevitable. “Ask any Saudi, anyone at all, whether MBS will be king,” a senior Saudi diplomat told me. “If there are people in Washington who think he will not be, then I cannot help them. I am not a psychiatrist.”

His father’s eventual death will leave him as the absolute monarch of the birthplace of Islam and the owner of the world’s largest accessible oil reserves. He will also be the leader of one of America’s closest allies and the source of many of its headaches.

I’ve been traveling to Saudi Arabia over the past three years, trying to understand if the crown prince is a killer, a reformer, or both—and if both, whether he can be one without the other.

Even MBS’s critics concede that he has roused the country from an economic and social slumber. In 2016, he unveiled a plan, known as Vision 2030, to convert Saudi Arabia from—allow me to be blunt—one of the world’s weirdest countries into a place that could plausibly be called normal. It is now open to visitors and investment, and lets its citizens partake in ordinary acts of recreation and even certain vices. The crown prince has legalized cinemas and concerts, and invited notably raw hip-hop artists to perform. He has allowed women to drive and to dress as freely as they can in dens of sin like Dubai and Bahrain. He has curtailed the role of reactionary clergy and all but abolished the religious police. He has explored relations with Israel.

He has also created a climate of fear unprecedented in Saudi history. Saudi Arabia has never been a free country. But even the most oppressive of MBS’s predecessors, his uncle King Faisal, never presided over an atmosphere like that of the present day, when it is widely believed that you place yourself in danger if you criticize the ruler or pay even a mild compliment to his enemies. MBS’s critics—not regicidal zealots or al‑Qaeda sympathizers, just ordinary people with independent thoughts about his reforms—have gone into exile. Some fear that if he keeps getting his way, the modernized Saudi Arabia will oppress in ways the old Saudi Arabia never imagined. Khalid al-Jabri, the exiled son of one of MBS’s most prominent critics, warned me that worse was yet to come: “When he’s King Mohammed, Crown Prince MBS is going to be remembered as an angel.”

Don’t miss what matters. Sign up for The Atlantic Daily newsletter.

For about two years, MBS hid from public view, as if hoping the Khashoggi murder would be forgotten. It hasn’t been. But the crown prince still wants to convince the world that he is saving his country, not holding it hostage—which is why he met twice in recent months with me and the editor in chief of this magazine, Jeffrey Goldberg.

In our meetings, the crown prince was charming, warm, informal, and intelligent. But even at its most affable, absolute monarchy cannot escape weirdness. For our first meeting, MBS summoned us to a remote palace by the Red Sea, his family’s COVID bunker. The protocols were multilayered: a succession of PCR tests by nurses from the Royal Clinics; a Gulfstream jet in the middle of the night from Riyadh; a convoy from a deserted airstrip; a surrender of electronic devices; a stopover at a mysterious guesthouse visible in satellite photos but unmarked on Google Maps. He invited us to his palace at about 1:30 a.m., and we spoke for nearly two hours.

For the second meeting, in his palace in Riyadh, we were told to be ready by 10 a.m. It also began after midnight. The halls were astir. The crown prince had just returned after nearly two years of remote work, and aides and ministers padded red carpets seeking meetings, their first in months, with the boss. Neglected packages and documents had piled up on the desks and tables in his office, which was large but hardly opulent. The most obvious concession to high taste was an old-fashioned telescope on a tripod, its altitude set shallow enough that it appeared to be pointed not at the heavens but at Riyadh, the sprawling and unsightly desert metropolis from which the Saud family has ruled for most of the past three centuries.

At the outset of both conversations, MBS said he was saddened that the pandemic precluded giving us hugs. He apologized that we all had to wear masks. (Each meeting was attended by multiple, mainly silent princes wearing identical white robes and masks, leaving us unsure, to this day, who exactly was present.) The crown prince left his tunic unbuttoned at the collar, in a casual style now favored by young Saudi men, and he gave relaxed, nonpsychopathic answers to questions about his personal habits. He tries to limit his Twitter use. He eats breakfast every day with his kids. For fun, he watches TV, avoiding shows, like House of Cards, that remind him of work. Instead, he said without apparent irony, he prefers to watch series that help him escape the reality of his job, such as Game of Thrones.

Make your inbox more interesting with newsletters from your favorite Atlantic writers.

Browse NewslettersBefore the meetings, I asked one of MBS’s advisers if there were any questions I could ask his boss that he himself could not. “None,” he answered, without pausing—“and that is what makes him different from every crown prince who has come before him.” I was told he derives energy from being challenged.

During our Riyadh encounter, Jeff asked MBS if he was capable of handling criticism. “Thank you very much for this question,” the prince said. “If I couldn’t, I would not be sitting with you today listening to that question.”

“I’d be in the Ritz-Carlton,” Jeff suggested.

“Well,” he said, “at least it’s a five-star hotel.”

Difficult questions caused the crown prince to move about jumpily, his voice vibrating at a higher frequency. Every minute or two he performed a complex motor tic: a quick backward tilt of the head, followed by a gulp, like a pelican downing a fish. He complained that he had endured injustice, and he evinced a level of victimhood and grandiosity unusual even by the standards of Middle Eastern rulers.

When we asked if he had ordered the killing of Khashoggi, he said it was “obvious” that he had not. “It hurt me a lot,” he said. “It hurt me and it hurt Saudi Arabia, from a feelings perspective.”

“From a feelings perspective?”

“I understand the anger, especially among journalists. I respect their feelings. But we also have feelings here, pain here.”

The crown prince has told two people close to him that “the Khashoggi incident was the worst thing ever to happen to me, because it could have ruined all of my plans” to reform the country.

In our Riyadh interview, the crown prince said that his own rights had been violated in the Khashoggi affair. “I feel that human-rights law wasn’t applied to me,” he said. “Article XI of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that any person is innocent until proven guilty.” Saudi Arabia had punished those responsible for the murder, he said—yet comparable atrocities, such as bombings of wedding parties in Afghanistan and the torture of prisoners in Guantánamo Bay, have gone unpunished.

The crown prince defended himself in part by asserting that Khashoggi was not important enough to kill. “I never read a Khashoggi article in my life,” he said. To our astonishment, he added that if he were to send a kill squad, he’d choose a more valuable target, and more competent assassins. “If that’s the way we did things”—murdering authors of critical op-eds—“Khashoggi would not even be among the top 1,000 people on the list. If you’re going to go for another operation like that, for another person, it’s got to be professional and it’s got to be one of the top 1,000.” Apparently, he had a hypothetical hit list, ready to go. Nevertheless, he maintained that the Khashoggi killing was a “huge mistake.”

“Hopefully,” he said, no more hit squads would be found. “I’m trying to do my best.”

If his best is not good enough for Joe Biden, MBS said, then the consequences of running a moralistic foreign policy would be the president’s to discover. “We have a long, historical relationship with America,” he said. “Our aim is to keep it and strengthen it.” Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris have called for “accountability” for Khashoggi’s murder, as well as the humanitarian disaster in Yemen, due to war between Saudi Arabia and Iranian-backed Houthi rebels. The Americans also refuse to treat him as Biden’s counterpart—Biden’s peer is the king, they insist—even though the crown prince rules the country with his father’s blessing. This stings. MBS has lines open to the Chinese. “Where is the potential in the world today?” he said. “It’s in Saudi Arabia. And if you want to miss it, I believe other people in the East are going to be super happy.”

We asked whether Biden misunderstands something about him. “Simply, I do not care,” he replied. Alienating the Saudi monarchy, he suggested, would harm Biden’s position. “It’s up to him to think about the interests of America.” He gave a shrug. “Go for it.”

Also risible to the crown prince was the notion that his citizens fear speaking out against him. We need dissent, he said, “if it’s objective writing, without any ideological agenda.” In practice, I noted, dissent seemed to be nonexistent. In September 2017, MBS ordered a boycott of Qatar, citing the country’s support for the Iranian government, the Muslim Brotherhood, al‑Qaeda, and other Islamist organizations in the region. His tiny neighbor suddenly transformed from official friend into official villain, and those expressing a kind word toward it disappeared into prison.

These sentiments, apparently, did not count as objective or nonideological. Qatar, MBS said, was comparable to Nazi Germany. “What do you think [would have happened] if someone was praising and trying to push for Hitler in World War II?” he asked. “How would America take that?” Of course Saudis would react strongly to Nazi sympathizers in their midst. Three years later, however, the countries reconciled, and the Saudi government tweeted out a photo of MBS and Hitler—that is, Qatari Emir Tamim Al Thani—wearing board shorts and smiling at MBS’s Red Sea palace. “Sheikh Tamim’s an amazing person,” MBS said. The fight between them had been no big deal, “a fight between brothers.” The relationship is now “better than ever in history.” The dissenters remain in prison, however, and I do not mean the Ritz-Carlton.

As for the actual Ritz-Carlton prisoners: They had it coming, the crown prince said. Overnight he’d rounded up hundreds of the most prominent Saudis, delivered them to Riyadh’s most lavish hotel, and refused to let them go until they confessed and paid up. I said that sounded like he was eliminating rivals. MBS looked incredulous. “How can you eliminate people who don’t have any power to begin with?” If they had power, he would not have been able to force them into the Ritz.

The Ritz operation, MBS said, was a blitzkrieg against corruption, and wildly successful and popular because it started at the top and did not stop there. “Some people thought Saudi Arabia was, you know, just trying to get the big whales,” MBS said. They assumed that after the government extracted settlements from the likes of Alwaleed bin Talal, the kingdom’s richest man, corruption at lower levels would resume. MBS noted, proudly, that even the minnows had been hooked. By 2019, everyone “understood that even if you steal $100, you’re going to pay for it.” In just a few months, he claims to have recovered $100 billion directly, and says that he will recover much more indirectly, as dividends of deterrence.

MBS acknowledged that to outsiders the Ritz operation may have looked thuggish. But to him it was an elegant, and by the way nonviolent, solution to the problem of vampires feasting on the kingdom’s annual budget. (An adviser to MBS told me that one alternative his aides had suggested was executing a few prominent corrupt officials.) During the months that the Ritz served as a prison, the kingdom’s financial regulator was essentially made king pro tempore, to devote the full power of the government to bleeding the vampires dry. But the Ritz guests had not, MBS said, been placed under arrest. That would imply that they had entered the court system and faced charges. Instead, he said, they had been invited to “negotiate”—and to his pleasure, 95 percent did so. “That was a strong signal,” he said. I’m sure it was.

The Saudi throne does not, like the British throne once did, just pass to the next male heir. The king chooses his successor, and ever since the founding king of the modern Saudi state, Abdulaziz, chose his son Saud as crown prince in 1933, each king has chosen another son of Abdulaziz. (He had 36 sons—with multiple wives and concubines—who survived to adulthood.) All were old enough to remember the camels-and-tents days, before extreme wealth, and they ruled conservatively, as if to lock in their gains. Even the shrewdest and most ambitious kings accomplished little. Abdullah, who took power in 2005, began as a reformer, but much of the momentum of the first half of his reign was lost as he doddered in the second, and the royal treasury was looted. (One notorious alleged thief in the Ritz, a major figure in the Royal Court, was said to have stolen tens of billions of dollars during His Majesty’s decline.)

Salman, the current king and at 86 one of the youngest of Abdulaziz’s brood, saw the perils of unchecked gerontocracy and anointed a successor from the next generation. His choice of Mohammed was not obvious. King Salman’s sons include Faisal, 51, who has a doctorate in international relations from Oxford; and Sultan, 65, a former Royal Saudi Air Force pilot who in 1985 spent a week on the space shuttle Discovery as a payload specialist. Either of these competent and educated men, citizens of the world, might have been a natural successor. But Salman had an inkling that the next king would need a certain grit and fluency with power that cannot be acquired in a seminar or a flight simulator. The new generation, born into luxury, tended to be soft, and the next king would need to be a modern version of a desert warlord like his grandfather.

Outside the immediate family, Salman considered his nephew Mohammad bin Nayef, who is known as MBN, appointing him crown prince in 2015, when he was 55. As a spymaster and security official in the 2000s, MBN had led the country’s domestic war against al‑Qaeda, and in the process had become well connected with counterparts in Washington and London. In 2009, MBN was injured when an al‑Qaeda bomber packed his underpants with explosives and approached him at an event.

Foreign governments considered MBN a safe pick: old enough but not too old, a proven fighter, respected overseas. But for Salman he was merely a throne-warmer for his son. (MBS had held no high office prior to his father’s coronation and needed a couple of years as defense minister to burnish his CV.) In 2017, Salman fired MBN. When you fire a prince, you fire all those who staked their fortunes on his rise; among the opponents of MBS are foreign governments who had planned for the reign of King MBN, and Saudis whose wealth and influence flowed from him. MBN’s chief adviser, Saad al-Jabri, fled to Canada. He alleges that MBS sent a team there to kill him. MBS’s government alleges that al-Jabri stole a massive fortune and is bankrolling efforts to defame the crown prince. (Both parties deny the claims.) “MBN survived al-Qaeda,” al-Jabri’s son Khalid told me. “But he couldn’t survive his own cousin.”

Others have suggested Salman’s younger brother Ahmed, a well-liked former deputy interior minister, as a throne-worthy alternative to MBS. Ahmed reportedly opposed MBS’s appointment as crown prince. In 2020, he was arrested on suspicion of treason.

Having consolidated power, MBS focused on Vision 2030. He is exasperated by the rest of the world’s failure to acknowledge how well it has gone. “Saudi Arabia is a G20 country,” he said. “You can see our position five years ago: It was almost 20. Today, we are almost 17.” He noted strong non-oil GDP growth, and reeled off statistics about foreign direct investment, Saudi overseas investment, and the share of world trade that passes through Saudi waters. The economic success, the concerts, the social reform—these are all done deals, he said. “If we were having this interview in 2016, you would say I’m making assumptions,” he said. “But we did it. You can see it now with your eyes.”

He was not lying. Between my first visit to Saudi Arabia, in 2019, and this conversation two years later, I had gone to the movies in Riyadh and sat next to a Saudi woman I had never met. She wore jeans and canvas sneakers, and she bounced her bare ankle while we watched Zombieland: Double Tap. When I first visited, I ate at restaurants that had cinder-block walls dividing single men on one side from women and families on the other. These were sledgehammered down—a little Berlin 1989 in every restaurant—and now men and women can eat together without eliciting so much as a sideways glance from fellow diners.

Many of the crown prince’s most persistent critics approve of these changes, and wish only that they had come sooner. (Khashoggi was such a critic. When I met him in London for brunch, shortly before his death, I asked him to list MBS’s failings. He said “90 percent” of the reforms were prudent and overdue.) The most famous Saudi women’s-rights activist, Loujain al-Hathloul, campaigned for women’s right to drive, and against the Saudi “guardianship law,” which prevented women from traveling or going out in public without a male relative. Al‑Hathloul was thrown in prison on terrorism charges in 2018—after MBS and his father had announced the imminent end of both policies. In prison, her family says, she was electrocuted, beaten, and—this was just a few months before Khashoggi’s murder—threatened with being chopped up and thrown in a sewer, never to be found. (The Saudi government has previously denied allegations of torturing prisoners.)

Al-Hathloul and other activists had demanded rights, and the ruler had granted them. Their error was in thinking those rights were theirs to take, rather than coming from the monarch, who deserved credit for having bestowed them. Al-Hathloul was released in February 2021, but her family says she is forbidden from traveling abroad or speaking publicly.

Another dissident, Salman al-Awda, is a preacher with a massive following. His original crime, too, was to utter publicly a thought that would later be shared by the crown prince himself. When MBS began squabbling with his counterpart in Qatar, al‑Awda tweeted, “May God harmonize between their hearts, for the good of their people.” He was imprisoned, and actual harmony between the two leaders has not freed him. His son Abdullah, now in the United States, claims that his father, who is 65, is being held in solitary confinement and has been tortured.

Saudi authorities say al-Awda is a terrorist and a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, which is supported by Qatar and intent on overthrowing the monarchy and replacing it with a theocracy. (The Muslim Brotherhood plays a bogeyman role in the Saudi imagination similar to the role of Communists in America during the Red Scare. Also like Communists, the Muslim Brotherhood really has worked covertly to undermine state rule, just not to the extent imagined.) Al-Awda’s defenders say he is being punished for daring to speak with a moral voice independent of the monarchy’s. He faces death by beheading.

Would MBS consider pardoning those who’d spoken out in favor of women driving and normalization with Qatar—both now the policy of the country? “That’s not my power. That’s His Majesty’s power,” MBS said. But, he added, “no king has ever used” the pardon power, and his father does not intend to be the first.

The issue, he said, is not a lack of mercy. It is a problem of balance. Yes, there are liberals and kumbaya types who have run afoul of state security—and perhaps some could be candidates for a royal pardon. But some of the others in his jails are bad hombres indeed, and pardons cannot be meted out selectively. “You have, let’s say, extreme left and extreme right,” he said. “If you give forgiveness in one area, you have to give it to some very bad people. And that will take everything backward in Saudi Arabia.”

On one side are liberals, tugging on the sympathies of Westerners; on the other, Islamists who are also opposed to the monarchy. Letting this latter group out would not just mean the end of rock concerts and coed dining. They would not stop until they brought down the House of Saud, seized the country’s estimated 268 billion barrels of oil and the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, and established a terrorist state. In private conversations with others, MBS has likened Saudi Arabia before the Saud family’s conquest in the 18th century to the anarchic wasteland of the Mad Max films. His family unified the peninsula and slowly developed a system of law and order. Without them, it would be Mad Max all over again—or Afghanistan.

Still, the crown prince’s argument—that if he extended forgiveness to good people who deserved it, he would have to extend it equally to bad people who did not—struck me as bizarre. Why would one require the other? Then I realized that MBS was not saying that the failure of his plan to remake the kingdom might lead to catastrophe. He was saying that he’d guarantee it would. Many secular Arab leaders before him have made the same dark implication: Support everything I do, or I will let slip the dogs of jihad. This was not an argument. It was a threat.

Ali Shihabi, a Saudi financier and pro-MBS commentator, told me that the changes in Saudi Arabia could be compared to those in revolutionary France. An old order had been overturned, a priestly class crushed; a new order was struggling to be born.

The priestly class in particular interested me. The brand of conservative Islam practiced in Saudi Arabia—called Wahhabism, after the sect’s 18th-century founder, Muhammad ibn Abd al‑Wahhab—once wielded great power and enjoys at least some popular support. I asked Shihabi if MBS really had diminished the Wahhabis’ role. “Diminished their role?” Shihabi asked me. “He put the Wahhabis in a cage, then he reached in with gardening shears”—here he made the universal snip snip gesture with his fingers—“and he cut their balls off.”

In France, revolution worked out just as badly for the House of Bourbon as it did for the clergy. (Diderot famously wrote that the entrails of the priests would be woven into ropes to strangle kings.) The House of Saud wanted the anticlerical revolution while conveniently omitting the antiroyalist one. I wanted to see how that alliance between monarch and sansculottes was working.

Vision 2030 made modernization easier to observe now than it would have been just a few years ago. Until October 2019, tourist visas to Saudi Arabia did not exist. Then the Saudis realized that to attract crowds to the concerts they had legalized, they’d need to let in visitors. Overnight, a visa to Saudi Arabia went from one of the hardest in the world to get to one of the easiest. In minutes I had one valid for a whole year. My flight into Riyadh was packed with foreigners attending Stan Lee’s Super Con. Ahead of me in the passport line I saw Lou Ferrigno, the Incredible Hulk, on his way to an autograph signing.

The new system arrived so fast that the first visitors were like an invasive species, an unnatural fit in the rigid social order of the kingdom. For years, almost every non-Saudi in the country had needed a document called an iqama. It was a sort of license to exist: Your iqama identified your Saudi patron, the local national whom you were visiting or working for, and who controlled your fate. Every Saudi patron had his own patron, too—sometimes a tribal leader, sometimes a regional one. Even those bigwigs paid obeisance to someone and, eventually, by the transitive property of Saudi deference, to the king himself. Saudi Arabia, MBS explained, “is not one monarchy. You have beneath it more than 1,000 monarchies—town monarchies, tribal monarchies, semitribal monarchies.” The iqama guaranteed that every sentient creature fit into this scheme of Saudi society.

MBS batted away my suggestion that this system is antiquated and might be replaced with a constitutional monarchy—one where citizens have freestanding rights not granted by a monarch or a demi-monarch. “No,” he said. “Saudi Arabia is based on pure monarchy,” and he, as crown prince, would preserve the system. To remove himself from it would amount to a betrayal of all the monarchies and Saudis beneath him. “I can’t stage a coup d’état against 14 million citizens.”

But he has already forced that system to adapt. Nearly every day someone asked for my iqama, and I had to explain that I had none. They reacted as if I’d told them that I had no name. Renting a car, buying a train ticket, checking into a hotel—all of these interactions left some poor clerk baffled. But in the new Saudi Arabia I was free to wander, to listen, to overhear.

In Riyadh I found, effortlessly, young people thrilled by the reforms. Like the other major Saudi cities, Dammam and Jeddah, Riyadh has specialty coffee shops in abundance—little outposts of air-conditioning and caffeine, in an environment otherwise characterized by heat and boredom. Many of the Saudis I met professed a deep love for America. “I spent seven years at Cal State Northridge,” one told me, before rattling off a list of cities he had visited. He was one of several hundred thousand Saudi students who’d attended U.S. universities on government scholarships in the 2000s. “I studied finance,” he said. “But I never graduated. I had a wonderful time.” He listed his American friends, who had names like Mike and Emilio. “I drank and did too much meth, and my grades weren’t good.”

“Is it possible to do just the right amount of meth?” I asked.

“When I came back, I stopped.” He looked out the window of the coffee shop at the parched cityscape. “This country is the best rehab center on the planet.”

Now he was studying again, at a Saudi university, and planning to open his own business. He had already attended concerts, and he said his fondest wish was to listen to music in the open air and smoke a joint—just one, he promised. He asked if I thought that would happen. I said I did not think that was explicitly part of Vision 2030, but he’d probably get his wish. Later, with him in mind, I asked the crown prince whether alcohol would soon be sold in the kingdom. It was the only policy question that he refused to answer.

In another café, in the northern city of Ha’il, a man pointed to a mural, freshly painted, of the Lebanese singer Fairouz, her hair flowing beautifully over her shoulders. Next to her were her lyrics (in Arabic): “Bring me the flute and sing, for song is the secret to eternity.”

“One year ago,” he said, “that would not be possible.” By “that,” he meant pretty much everything: a woman’s hair; a celebration of song; a celebration of a song about singing; and, on top of all this, the music playing in the café as we spoke. Before the rise of MBS, every component of this scene would have violated long-standing canons of Saudi morality enforcement. The religious police, known in Arabic as the hay’a or mutawwi’in, would have busted the joint. They used to show up in ankle-length white thobes, their beards curly and unkempt. They yelled at people for dressing immodestly, or thwacked at them with sticks to goad them to the mosque for one of the five daily prayers. For the flagrancy of the Fairouz sins, the café’s managers would have been detained, questioned, and punished. “Screw those guys,” the man said, in a succinct expression of the most common sentiment I heard about the religious police.

Encounters with the hay’a have provided many an appalling story for foreign visitors. When Maureen Dowd of The New York Times went to Riyadh in 2002, the hay’a spotted her in a shopping mall and objected to being able to see the outline of her body. Her host, the future foreign minister Adel al-Jubeir, pleaded with them, but they were unimpressed by his status as a prominent diplomat, and she fled to her hotel room. “I fretted that I was in one of those movies where an American makes one mistake in a repressive country and ends up rotting in a dungeon,” Dowd wrote.

I told one of MBS’s advisers that the religious police had been an international PR problem. “May I be impolite?” he asked me. “I don’t give a fuck about the foreigners. They terrorized us.” He likened the religious police to J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, operating with unchecked authority. (The religious police’s official Arabic name dates back hundreds of years, but still sounds Orwellian in English: the Committee for the Prevention of Vice and Promotion of Virtue.) Anyone who wished to drag down a professional or political rival could scrutinize him for sins, then call the religious police to set up a sting. Or the hay’a could flex its authority on its own, either for political reasons—toppling a prince they disliked—or for recreation.

“The religious police were the losers in school,” Ali Shihabi told me. “Then they got these jobs and were empowered to go and stop the cute girls, break into the parties no one wanted them at, and shut them down. It attracted a very nasty group of people.” The Saudi diplomat told me that he did not miss them, and that Saudi Arabia had needed someone with the crown prince’s mettle to get rid of them. “When someone hits you because he does not like what you are wearing,” he said, “that is not just a form of harassment. It is abuse.”

MBS ordered the religious police to stand down, and one of the enduring mysteries of contemporary Saudi Arabia is what these thwackers do, now that they are invisible on the streets. Fuad al-Amri, who runs the hay’a in Mecca province, confessed to me that since the reforms, one of his main activities has been vetting his own employees, to ensure that they aren’t fanatics loyal to the Muslim Brotherhood.

MBS’s grandfather King Abdulaziz founded the modern Saudi state with the support of the clergy. But he also cracked down on them, hard, when they outlived their usefulness. MBS has recounted a famous anecdote about his grandfather. In 1921, Abdulaziz attended the funeral of the most senior religious scholar in the kingdom. The king told the assembled clerics that they were dear to his heart—in the Arabic idiom, “on my iqal,” the black cord that holds a Najd headdress in place. But then he warned them: “I can always shake my iqal,” he said, “and you will fall.”

For the past 50 years, Abdulaziz’s successors have taken a softer line with the Wahhabis. The Saudi clerical class’s power grew, and their imprimatur mattered. In 1964, they sealed the fate of the inept King Saud when his brothers Faisal and Mohammed sought and received religious approval for ousting him. To oppose the religious conservatives was risky. Peter Theroux, a former National Security Council director who worked on the Saudi portfolio during the 2000s, recalls being aghast at the vicious sermons still being preached by government-paid imams years after September 11. Theroux told me he confronted a senior Saudi official about the sermons. “You know,” the official apologized, “the big beards are kind of our constituency.” The rulers of Saudi Arabia put almost no limits on the speech or behavior of conservative clerics, and in return those clerics exempted the rulers from criticism. “That was the drug deal that the Saudi state was based upon for many years,” Theroux told me. “Until Mohammed bin Salman.”

Who could resist cheering on MBS as he renegotiated this relationship? One of MBS’s most persistent critics in Washington, Senator Chris Murphy, a Democrat from Connecticut, told me the concerts and Comic-Cons in Riyadh have not yet translated into defunding Wahhabi intolerance overseas. “When I’m traveling the world, I still hear story after story of Gulf money and Saudi money fueling very conservative, intolerant Wahhabist mosques,” he said. A hallmark of traditional Wahhabism is hatred for non-Wahhabi Muslims, whom the Wahhabis view as even worse than unbelievers for perverting the faith. With little modification, Wahhabi teachings can lead to Osama bin Laden–style jihadism. Murphy said he thinks that isn’t over. “The money that flows from Saudi Arabia into conservative Islam isn’t as transparent as it was 10 years ago—much of it has been driven underground—but it still exists.”

Yet after spending hours in MBS’s company, and in the company of his allies and enemies, I was convinced that neutering the clergy was not just symbolic. He was fighting them avidly, and personally. “The kings have historically stayed away from religion,” Bernard Haykel, a scholar of Islamic law at Princeton and an acquaintance of MBS’s, told me. Outsourcing theology and religious law to the big beards was both an expedient and a necessity, because no ruler had any training in religious law, or indeed a beard of any significant size.

By contrast, MBS has a law degree from King Saud University and flaunts his knowledge and dominance over the clerics. “He’s probably the only leader in the Arab world who knows anything about Islamic epistemology and jurisprudence,” Haykel told me.

“In Islamic law, the head of the Islamic establishment is wali al-amr, the ruler,” MBS explained. He was right: As the ruler, he is in charge of implementing Islam. Typically, Saudi rulers have sought opinions from clerics, occasionally leaning on them to justify a policy the king has selected in advance. MBS does not subcontract his religion out at all.

He explained that Islamic law is based on two textual sources: the Quran and the Sunna, or the example of the Prophet Muhammad, gathered in many tens of thousands of fragments from the Prophet’s life and sayings. Certain rules—not many—come from the unambiguous legislative content of the Quran, he said, and he cannot do anything about them even if he wants to. But those sayings of the Prophet (called Hadith), he explained, do not all have equal value as sources of law, and he said he is bound by only a very small number whose reliability, 1,400 years later, is unimpeachable. Every other source of Islamic law, he said, is open to interpretation—and he is therefore entitled to interpret them as he sees fit.

The effect of this maneuver is to chuck about 95 percent of Islamic law into the sandpit of Saudi history and leave MBS free to do whatever he wants. “He’s short-circuiting the tradition,” Haykel said. “But he’s doing it in an Islamic way. He’s saying that there are very few things that are fixed beyond dispute in Islam. That leaves him to determine what is in the interest of the Muslim community. If that means opening movie theaters, allowing tourists, or women on the beaches on the Red Sea, then so be it.”

MBS rebuked me when I called this attitude “moderate Islam,” though his own government champions the concept on its websites. “That term would make terrorists and extremists happy.” It suggests that “we in Saudi Arabia and other Muslim countries are changing Islam into something new, which is not true,” he said. “We are going back to the core, back to pure Islam” as practiced by Muhammad and his four successors. “These teachings of the Prophet and the four caliphs—they were amazing. They were perfect.”

Even the Islamic law that he is bound to implement will be implemented sparingly. MBS told me a story, reported in Hadith, about a woman who commits fornication, confesses her crime to the Prophet, and begs to be executed. The Prophet repeatedly tells her to go away—implying, the crown prince said, that the Prophet preferred to give sinners every chance at lenience. (MBS did not relate the end of the tale: The woman returns with indisputable evidence of her sin—a bastard son—and the Prophet acquiesces. She is buried to her chest and stoned to death.)

Instead of hunting for sin and punishing it as a matter of course, MBS has curtailed the investigative function of the religious police, and encourages sinners to keep their transgressions between themselves and God. “We should not try to seek out people and prove charges against them,” he said. “You have to do it the way that the Prophet taught us how to do it.” The law will be enforced only against those so flagrant that they are practically demanding to take their lumps.

He also stressed that none of these laws applies to non-Muslims in the kingdom. “If you are a foreign person who’s living or traveling in Saudi Arabia, you have all the right to do whatever you want, based on your beliefs,” he said. “That’s what happened in the Prophet’s time.”

It is hard to exaggerate how drastically this sidelining of Islamic law will change Saudi Arabia. Before MBS, influential clerics issued fatwas exhibiting what might charitably be called a pre-industrial view of the world. They declared that the sun orbited the Earth. They forbade women from riding bikes (“the devil’s horses”) and from watching TV without veiling, just in case the presenters could see them through the screen. Salih al-Fawzan, the most senior cleric in the kingdom today, once issued a chillingly anti-American fatwa forbidding all-you-can-eat buffets, because paying for a meal without knowing what you’ll be eating is akin to gambling.

Some of the clerics may have given in because they were convinced by the crown prince’s legal interpretations. Others appear to have succumbed to good old-fashioned intimidation. Formerly conservative clerics will look you in the eye and without hesitation or scruple speak in Stepfordlike coordination with the government’s program. The minister of Islamic affairs and guidance, normally an unsmiling type, now cheerily defended the opening of cinemas and mass layoffs of Wahhabi imams. I liked him immediately. His name, Abdullatif Al Asheikh, indicates that he is descended from a long line of stern moralists going back to Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab himself. I told him I had seen the Zombieland sequel in his country, and if Woody Harrelson reprised his role in Zombieland 3, I would return to Riyadh so we could go to a theater and watch it together. “Why not?” he replied.

Mohammad al-Arefe, a preacher known for his good looks and conservative views, mysteriously began promoting Vision 2030 after a meeting with MBS in 2016. Previously, he had preached that Mada’in Saleh, a spectacular pre-Islamic archaeological site in northwest Saudi Arabia, was forbidden to Muslim tourists. God had struck down the civilization that once lived there, and the place was forever to remain a reminder of his wrath. The conventional view held that Muslims should follow the Prophet’s warning to stay away from Mada’in Saleh, but if they absolutely must pass through, they should cast their gaze downward and maintain a fearful demeanor toward the Almighty. Then, in 2019, al-Arefe appeared in what seemed, to me, like some sort of hostage video, filmed by the Saudi tourism authority, lecturing about the site’s history and inviting all to enjoy it. If he was displaying a fearful demeanor, it was not toward the Almighty.

In the smaller cities it isn’t clear how quickly modernization is catching on. I visited Buraydah, the capital of Qassim, the most conservative part of the country. In two days, every woman I saw wore a black, flowing abaya. I attended the opening of a new shopping mall and showed up early to watch the crowds arrive. The sexes separated themselves without discussion: women in the front, all in black, near the stage where children recited poems and sang; men, in white thobes, in the back of the audience and on the sides. The process was unconscious and organic, but to an outsider remarkable, as if salt and pepper were shaken out onto a plate, and the grains slowly and perfectly segregated themselves. Cultural practices decades or centuries old do not yield suddenly.

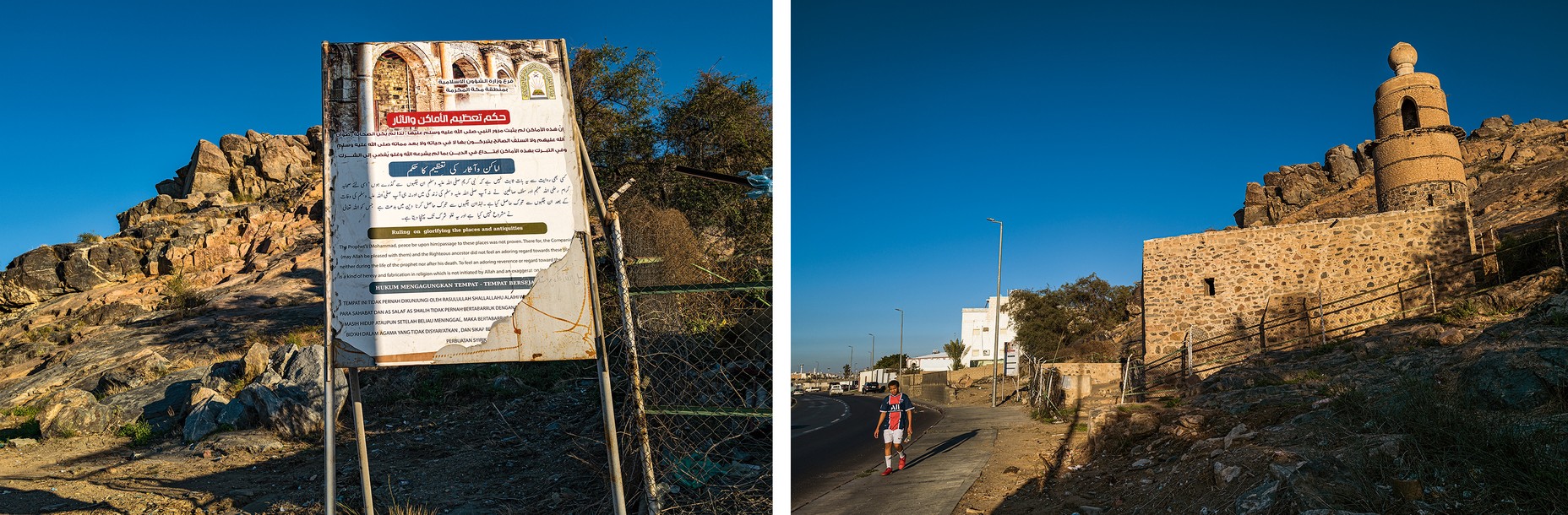

Taif, a city an hour outside Mecca, was once the summer residence of the king and his family. The Prophet is thought to have visited there, and many Muslims supplement their pilgrimages to Mecca with side trips to other sites from the Prophet’s life. The Wahhabis have, historically, treated these visits as un-Islamic and reprehensible. Whenever pilgrimage sites have fallen into Wahhabi hands, they have methodically and remorselessly destroyed them by leveling monuments, grave markers, and other structures sacred to Muslims in other traditions.

One morning I took a long walk to a mosque where the Prophet is said to have prayed. On arrival I found a building in disrepair, fenced off by rusty wire, with parts of it reduced to rubble. A sign at this site, posted by the Ministry of Islamic Affairs, noted in Arabic, Urdu, Indonesian, and English that the historical evidence for the Prophet’s visit was uncertain. It suggested, further, that “to feel an adoring reverence or regard toward these places is a kind of heresy and fabrication in religion,” an innovation not sanctioned by God that “leads to polytheism.”

Later, I met Mohammad al-Issa, formerly the minister of justice under King Abdullah and now, as secretary-general of the Muslim World League, an all-purpose interfaith emissary for his country. In the past, Saudi clerics inveighed against infidels of all types. Now al-Issa spends his time meeting Buddhists, Christians, and Jews, and trying to stay ahead of the occasional surfacing of comments he made in less conciliatory times. I asked him about the site, and whether Saudi Arabia’s new tolerance—which he emphasizes so energetically overseas, with non-Muslims—would apply domestically. He assured me that it already did. “If in the past there were some mistakes, now there is correction,” al‑Issa said. “Everyone has the right to visit the historic places, and there is a lot of care given to them.”

“But the signs are still up,” I said.

“Maybe they are there to remind people to be respectful,” he suggested. “You see signs like that at sites all over the world: ‘Don’t touch or take the stones.’ ”

But these signs are not meant to preserve the ruins. They are there to remind you that you are wicked for visiting at all.

The day after my trip to the mosque, I stopped by a Starbucks in Taif. It was early afternoon. When I pulled the door handle, it clunked—the shop was closed for prayer, just as it would have been if the religious police had been enforcing prayer times.

As I waited outside alone, a small police truck pulled up behind me. The police officer salaamed me, and I responded in Arabic. Only after a short interrogation (“What are you doing here? Why are you here?”) did he discover that I was American—not, as I think he suspected, Filipino—and apologize awkwardly and leave. It took me a minute to realize what had happened: The religious police have stood down, and the ordinary police have stood up in their place. The conservatism in society has not gone away. In some places, it has just undergone a costume change.

These lingering manifestations of intolerance illustrate what MBS’s critics say is his ultimate error: Even a crown prince can’t change a culture by fiat.

Belated realization of this error might be behind the grandest and most improbable of his projects. If existing cities resist your orders, just build a new one programmed to do your bidding from the start. In October 2017, MBS decreed a city in a mostly uninhabited area on the Gulf of Aqaba, adjacent to Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, the southwestern edge of Jordan, and the Israeli resort town Eilat. The city is called Neom, from a violent collision between the Greek word neos (“new”) and the Arabic mustaqbal (“future”).

At present, little exists but an encampment for the employees of the Neom project, a small area of tract housing. Regular buses take them to shop in the nearest city, Tabuk, which is itself a city only by the standards of the vacant, rock-strewn desert nearby. (If you recall the early scenes of Lawrence of Arabia, when a lonely camel-borne Peter O’Toole sings “The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo” to the echoes of a sandstone canyon, then you know the spot.) The ambitions for this settlement are vast. Neom’s administrators say they expect it to attract billions of dollars in investment and millions of residents, both Saudi and foreign, within 10 to 20 years. Dubai grew at a similar pace in the 1990s and 2000s. MBS said Neom is “not a copy of anything elsewhere,” not a xerox of Dubai. But it has more in common with the great globalized mainstream than with anything in the history of a country that, until recently, was remarkably successful at walling off its traditional culture from the blandishments of modernity.

For a few hours, the Neom team showed me around and made grandiose promises about the future. Neom would lure its investors, I gathered, by creating the ideal regulatory environment, stitched together from best practices elsewhere. The city would profit from central planning. When New York or Delhi want to grow, they choke on their own traffic and decrepit infrastructure. Neom has no inherited infrastructure at all. The centerpiece of the project will be “The Line”—a 106-mile-long, very skinny urban strip connected by a single bullet train that will travel from end to end in 20 minutes. (No train capable of this speed currently exists.) The Line is intended to be walkable—the train will run underground—and a short hike perpendicular to its main axis will take you into pristine desert. Water will be desalinated; energy, renewable.

So far, Neom is less a city than an urbanist cargo cult. The practicalities can come later, or not at all. (The projected cost is in the hundreds of billions of dollars, a huge sum even for Saudi Arabia.) But many good ideas look crazy at first. What struck me was that Neom’s vision is really an anti-vision. It is the opposite of the old Saudi Arabia. In the old Saudi Arabia, and even to an extent today, corruption and bureaucracy layered on each other to make an entrepreneur’s nightmare. Riyadh has almost no public transportation. No matter where you are, you cannot walk anywhere, except perhaps to your local mosque. No one in Neom mentioned religion at all. Even Neom’s location is suggestive. It is far from where Saudis actually live. Instead it is huddled in a mostly empty corner, as if seeking sustenance and inspiration from Jordan and Israel.

Seen this way, Neom is MBS’s declaration of intellectual and cultural bankruptcy on behalf of his country. Few nations have as many carried costs as Saudi Arabia, and Neom zeroes them out and starts afresh with a plan unburdened by the past. To any parts of the kingdom that cling to their old ways, it promises that the future is everything they are not. And the future will wait only so long.

During the 1990s and 2000s, Saudi Arabia was a net exporter of vision, but it was a jihadist vision. The standard narrative, now accepted by the Saudi state itself, is that the kingdom was seduced by conservative Islam, and eventually the jihadists it sent overseas (most famously Osama bin Laden) redirected their efforts toward the Saudi monarchy and its allies. Fifteen of the 19 hijackers on 9/11 were Saudi citizens.

“A series of things happened that made the Saudis realize they couldn’t keep playing the game they had been playing,” Philip Zelikow, a State Department official under George W. Bush and the executive director of the 9/11 Commission, told me. The years of violence that followed 9/11 shocked the Saudis into realizing that they had a reckoning coming, though only after jihadists began attacking in the kingdom itself did the government move to crush them. What the Saudis did not have was a plan to redirect the jihadists’ energy. “They needed to have some story of what kind of country they were going to be when they grew up,” Zelikow said. Jihadism would not be that story. But there was no immediate alternative, either for society or for the individuals attracted to jihadism. Saudi Arabia was left to do what most other countries, including the United States, have done, which is to imprison terrorists until they grow too old to fight.

Last year, Saudi officials informed me that the crown prince had a new plan to deprogram jihadists. One morning they sent a convoy of state-security SUVs to my hotel, and with lights flashing, we left behind the glassy skyscrapers of the capital and continued along one of the straight, hypnotic roads radiating from Riyadh to nowhere. An hour later, we turned off at an area called al-Ha’ir and went through a security checkpoint.

Ha’ir is a state-security prison, run by the Saudi secret police, which means that its prisoners are not car thieves and check forgers but offenders against the state. They include jihadists from al-Qaeda and the Islamic State—I met at least a dozen of each—as well as softer Islamists, like Salman al-Awda, the cleric.

We drove past the checkpoint and through the gates, into a windswept compound coated in a film of light-brown dust, like tiramisu. We were met by the director of state-security prisons, Muhammad bin Salman al-Sarrah, and what appeared to be a television crew of at least half a dozen men, each bearing a microphone or a camera. I worried about what would happen next. Newsworthy events inside the walls of terrorist prisons tend not to be good. Lurking in the background were several bearded men in identical gray business suits.

Al-Sarrah, it turned out, was a real jihadism nerd, and over tea we reminisced about various luminaries in the history of Saudi terror. After this small talk, he invited me to join him in an auditorium that could have been a lecture hall on a small college campus. Shutters clicked as the cameramen followed.

In the auditorium, the men in suits took the stage. Their leader, a man named Abdullah al-Qahtani, explained that he and most of the others in the room were prisoners, and that they had a PowerPoint presentation they wished to show me about the enterprise they were running in the prison. The camera crew was made up of prisoners too, and they were documenting my visit for imprisoned members of jihadist sects.

What followed was the most surreal slide deck I have ever seen: a corporate org chart and plans for a set of businesses run from within the prison by jihadists and other enemies of the state. Al-Qahtani spoke in Arabic, translated by an excitable counterpart nearby.

The org chart showed CEO al-Qahtani at the top, with direct reports from seven offices beneath him, among them financial, business development, and “programs’ affairs.” Under the last of these was another sub-office, “social responsibility.”

Al-Qahtani explained that 89 percent of the prison population had taken part in the program so far. In a way, it was like any other prison-industry program; in the United States, prisoners staff call centers, raise tilapia, or just push brooms in the prison corridor for a dollar an hour. But the Ha’ir group, doing business as a company called, simply, Power, was aggressively corporate and entrepreneurial.

Al-Qahtani and the interpreter took me to a small garden, where prisoners cultivated peppers under plastic sheeting and raised bees and harvested their honey to sell at the prison shop, in little jars with the Power logo. They operated a laundromat and presented me with a price list. The prison will clean your clothes for free, they said, but staff and inmates alike could bring clothes here for special services, such as tailoring, for a fee. I could see shirts, freshly laundered and pressed, with prisoner numbers inked into the collars. Each number started with the year of entry on the Islamic calendar. I saw one that started in 1431, about 12 years ago.

Almost all the men wore thick beards, and many had a zabiba (literally “raisin”), the discolored, wrinkly spot one gets from pressing the head to the ground in prayer. Some of their products were artisanal and religious-themed. They led me into a tiny room, a factory for the production of perfumes for sale outside the prison, and to another room where they made prayer beads from olive pits.

“Here, smell this,” a former member of al-Qaeda commanded me, sticking under my nose a paper strip blotted with a chemical I could not identify. I think the scent was lavender. Another prisoner, at the Power-run prison canteen, offered me free frozen yogurt. As I walked around the prison, the yogurt began to melt, and my interpreter held it so I could take notes.

Strangest of all, I found, was Power’s corporate nerve center—a warren of drab, cubicle-filled offices. The employees wore uniforms: suits for the C-suite executives and blue Power-branded polo shirts for the mid-levels puttering on their computers. They had a conference room with a whiteboard (at the top, “In the name of God, the most gracious, most merciful” was written in Arabic, and partially erased; the rest was the remains of a sales brainstorming session), a reception desk, and portraits of the king and the crown prince overseeing it all.

Nothing is stranger than normalcy where one least expects it. These jihadists—people who recently would have sacrificed their life to take mine—had apparently been converted into office drones. Fifteen years ago, Saudi Arabia tried to deprogram them by sending them to debate clerics loyal to the government, who told the prisoners that they had misinterpreted Islam and needed to repent. But if this scene was to be believed, it turned out that terrorists didn’t need a learned debate about the will of God. They needed their spirits broken by corporate drudgery. They needed Dunder Mifflin.

My hyperactive interpreter, who had been gesticulating and yapping throughout the tour, was no ordinary jihadist. He was an American-born Saudi member of al-Qaeda named Yaser Esam Hamdi. Hamdi, now 41, emerged from a pile of rubble in northern Afghanistan in December 2001. His dear friend, pulled from the same rubble, was John Walker Lindh, the so-called American Taliban. Hamdi spent months in Guantánamo Bay before being transferred to the U.S.; he was released after his father, a prominent Saudi petrochemical executive, helped take Hamdi’s case to the Supreme Court, and won (Hamdi v. Rumsfeld ). Hamdi was sent back to Saudi Arabia on the condition that he renounce his U.S. citizenship (he was born in Louisiana and left as a small child), but the Saudis decided he needed more time in prison and locked him up for eight years in a facility in Dammam, and for another seven in Ha’ir. He is due for release this year.

Hamdi guided me like a kid showing his parents around his sleepaway camp. He explained that Power is part of a larger entity at the prison, known as the “Management of Time” (Idarat al-Waqt)—a comprehensive but amorphous program meant to beguile the inmates out of bad ideas and replace them with good ones. It involves corporate training, but also gathering the inmates together for song and music, for poetry readings, for the publishing of newspapers (I snagged a copy of the Management of Time News), and for the production of TV shows. I watched a room full of men sing a song they had written, “O My Country!,” and show videos in which they extolled the government and the crown prince. Al-Qaeda and ISIS forbid most music and revile the monarchy. Like so many other Saudis, these men seemed to have swapped their religious fanaticism for nationalist fanaticism. One wondered what they really believed.

Al-Sarrah followed close behind us, and I shot him a look when I heard the name of the program. One of the most famous jihadist texts, a playbook for ISIS, is “The Management of Savagery” (Idarat al-Tawahhush). It is a deranged manual for destroying the world and replacing it with a new one. That was what this program was doing in reverse: replacing the jihadists’ savage appetite for an imagined future with an appetite for the real, the now, and the ordinary.

I told Hamdi that I had corresponded with his friend Lindh, who served 17 years in federal prison in the United States before his release in 2019. Our correspondence had led me to believe that he was just as radical as ever, and that his stay in prison—spent in solitary study of Islamic texts—had confirmed his violent streak and converted him from an al-Qaeda supporter to an ISIS supporter.

“Really?” Hamdi asked, before venturing a guess as to why. “The United States doesn’t know how to deal with Muslims. When I was in Afghanistan, I had extreme thinking.” Going to a Saudi prison helped. “The difference is that in jail [here] we have a program. You want to explode the thinking we have in our brain. For 17 years he was alone.” The Saudis filled Hamdi’s time. They managed it. “We didn’t have time to read the Islamic books … We didn’t have time to do anything but work to improve ourselves.” He was a specialist in Power’s media department, and could now produce videos of passable quality.

“I didn’t know what a montage was,” he said. “I didn’t know what a design was.” We were driving to another part of the prison with al-Sarrah in the front seat and Hamdi and me in the back. “Now I am professional!” he said. “I am a complete montage expert!” He pointed at al-Sarrah, who smiled but did not speak or even look back. “All thanks to this man! The government opened this for us! Now I am in a car! Talking to you! Normally! Peacefully! No kind of problems!” Upon release, he said, he might work for his father’s company, or even (this was his dream) go into film and television production. I wondered what it might be like to have a co-worker like Hamdi, with, shall we say, an unconventional work history, and a penchant for extremism and Osama bin Laden that he swore up and down had been thoroughly replaced with a love for film and video production and the crown prince of Saudi Arabia. I was pretty sure Hamdi would be a better colleague than John Walker Lindh.

At the prison I asked many inmates how they could trade jihadism for these worldly things, which surely amounted to frippery compared with the chance to die in the path of God. They laughed, nervously, as if to ask what I was trying to do—get them to leave the prison and kill again? They were mostly still young, and they yearned for freedom. That they no longer wanted something thrilling and extraordinary was exactly the point. It is possible to have too much vision, or the wrong kind—some of them had gone to Syria, barely survived, and had had enough vision, thank you very much. “We don’t want anything but a normal life,” one told me. “I would be happy just to go outside, to walk on the Boulevard in Riyadh, to go to McDonald’s.”

“I went to Syria because I was offered to take part in a dream, the dream of a caliphate,” said another. Ali al-Faqasi al-Ghamdi, a bookish man who had been with bin Laden at Tora Bora, told me he now recognized such dreams as counterfeit. What, he asked, is the point of a big, exciting dream when it is a false one? A small ambition that can actually be fulfilled is preferable to a big one that cannot. He looked me steadily in the eye, like he was trying to convince me and not himself. “Vision 2030 is real.”

America must now decide whether that vision is worth encouraging. Twenty years ago, if you had told me that in 2022 the future king of Saudi Arabia would be pursuing a relationship with Israel; treating women as full members of society; punishing corruption, even in his own family; stanching the flow of jihadists; diversifying and liberalizing his economy and society; and encouraging the world to see his country and his country to see the world—Wahhabism be damned—I would have told you that your time machine was malfunctioning and you had visited 2052 at the earliest. Now that MBS is in power, all of these things are happening. But the effect is not as pleasing as I had hoped.

In 1804, another modernizing autocrat, Napoleon Bonaparte, arrested Louis Antoine, the duke of Enghien, on suspicion of sedition. The duke was young and foolish, and no great threat to Napoleon. But the future emperor executed him. Around Europe, monarchs were shocked: If this was how Napoleon treated a harmless naif like the duke, what could they expect from him as his power grew, and his domestic opposition dissolved in fear? The execution of Enghien alerted the most perceptive among them that Napoleon could not be managed or appeased. It took a decade of carnage to figure out how to stop him.

Enghien’s schemes wouldn’t have stopped Napoleon, and Khashoggi’s columns wouldn’t have stopped MBS. But his murder was a warning about the personality of the man who will be running Saudi Arabia for the next half century, and it is reasonable to worry about that man even when most of what he does is good and long overdue.

For now, MBS’s main request to the outside world, and especially the United States, is the usual request of misbehaving autocrats—namely, to stay out of his internal affairs. “We don’t have the right to lecture you in America,” he said. “The same goes the other way.” Saudi affairs are for Saudis. “You don’t have the right to interfere in our interior issues.”

But he acknowledges that the fates of the two countries remain linked. In Washington, many see MBS’s rise as abetted, perhaps even made inevitable, by American support. “There was a moment in time where the international community could have made it clear that the Khashoggi murder was the straw that broke the camel’s back, and that we weren’t willing to deal with MBS,” Senator Murphy told me. The Trump administration’s support, when MBS was at his most vulnerable, saved him. “If MBS ultimately becomes king,” Murphy said, “he owes no one bigger than Jared Kushner,” Trump’s personal envoy to the crown prince. (“You Americans think there is something strange about a ruler who sends his unqualified son-in-law to conduct international relations,” one Saudi analyst told me. “For us this is completely normal.”)

Some still hope that MBS will not accede to the throne. “Only one of the last five crown princes has eventually become king,” Khalid al-Jabri noted to me, optimistically. But everything I see suggests that his ascent is certain, and that the search for alternatives is forlorn. Two of those four also-ran crown princes were sidelined or replaced by MBS himself. The other two died of old age.

The United States needs its partners in isolating Iran, and MBS is a stalwart there. And even domestically, he remains in some ways the right man for the job. He is at least, as Philip Zelikow reminded me, not a ruler in denial. “We wanted Saudi leadership who would face their problems, and embark on an ambitious and incredibly challenging generational struggle to remake Saudi society for the modern world,” he told me. Now we have such a leader, and he is presenting a binary choice: support me, or prepare for the jihadist deluge.

MBS is correct when he suggests that the Biden administration’s posture toward him is basically recriminatory. Stop bombing civilians in Yemen. Stop jailing and dismembering dissidents. The U.S. might, on the margins, be able to persuade MBS to use a softer touch—but only by first persuading him that he will be rewarded for his good behavior. And no persuasion will be possible at all without acknowledging that the game of thrones has concluded and he has won.

Many of the exiles I spoke with said their best hope now is that the crown prince will mellow, and that elder Saudi wise men will keep him from destroying the country with rash decisions, like the fight with Qatar, or the murder of Khashoggi. MBS does have a sense that being capricious and impulsive can be costly. “If we run the country randomly,” he told me, “then the whole economy is going to collapse.” Others had tried that strategy: “That’s the Qaddafi way.”

King Salman has instituted measures ostensibly intended to force his son to govern more inclusively after Salman’s death. He changed the law of succession to prevent the next king from naming his own children, or indeed anyone from his own branch of the family, as his crown prince. I asked MBS if he understood that to be the rule, and he said yes. I asked if he had anyone in mind for the job. “This is one of the forbidden subjects,” he said. “You will be the last to know.”

When he is king, however, the rules will belong to him, and to ask him to abide by them against his wishes will be about as easy as negotiating from your suite at the Ritz-Carlton.

A crown prince with a subtler mind and a gentler soul might have implemented MBS’s reforms without resorting to his brutal methods. But it is pointless to consider policy in a state of childlike fantasy, as if it were possible to conjure some new Saudi monarch by closing your eyes and wishing him into existence. Open your eyes, and MBS will still be there. If he is not, then the man ruling in his place will not be an Arab Dalai Lama. He will be, at best, a member of the unsustainable Saudi old guard, and at worst one of the big beards of jihadism, now richer than Croesus and ready to fight. As MBS told me, to justify the Ritz operation, “It’s sometimes a decision between bad and worse.”

Since reality has handed us MBS, the question for America is how to influence him. This question is practical rather than moral: If your moralism drives him into a partnership with China, what good will it have been? A fundamental principle of Chinese foreign relations is butting out of other countries’ internal affairs and expecting the same from them. Certainly Beijing will not reprimand him for his treatment of dissidents.

In effect, both the Saudis and the Americans are now in the Ritz-Carlton, forced to bargain with a jailer who promises us prosperity if we submit to his demands, and Mad Max if we do not. The predicament is familiar, because it is the same barrel over which every secular Arab autocrat has positioned America since the 1950s. Egypt, Iraq, and Syria all traded semitribal societies for modern ones, and they all became squalid dictatorships that justified themselves as bulwarks against chaos.

Twenty years ago, Syria watchers praised Bashar al-Assad for his modernizing tendencies—his openness to Western influence as well as his Western tastes. He liked Phil Collins; how evil could he be? By now most everyone outside Damascus, Tehran, and Moscow recognizes him as Saddam Hussein’s only rival in the dubious competition for most evil Arab leader.

MBS has completed about three-quarters of the transition from tribal king with theocratic characteristics to plain old secular-nationalist autocrat. The rest of that transition need not be as ruthless as the beginning, but MBS shows no sign of letting up. The United States can, and should, make the case that Saudi Arabia’s security and development will demand different tools going forward. It might even suggest what those tools should be. But it probably cannot make MBS use them.

A more pragmatic approach is to make sure that the reforms he has instituted stick, and that the changes in Saudi culture become irreversible. The opening of the country and the forcible sidelining of a crooked royal class—these are hard changes to undo, and they bind even the absolute monarch who decreed them. Granting women driver’s licenses was ultimately a smooth process. Taking them back would disrupt millions of lives and sow protest across the kingdom. American influence can acknowledge and encourage such changes.

Sometimes this is how absolute power relaxes its grip: slowly, without anyone noticing. In England, the transition from absolute monarchy to a fully constitutional one took 200 years, not all of them superintended by the most stable kings. MBS is still young and hoarding power, and everyone who has predicted that he would ease up on dissent has so far been proved optimistic. But 50 years is a long reign. The madness of King Mohammed could give way to something else: a slow and graceful renunciation of power—or, as with Assad, an ever more violent exercise of it.

This article appears in the April 2022 print edition with the headline “Absolute Power.”