Novak Djokovic, age 35, sometimes hangs out in a pressurized egg to enrich his blood with oxygen and gives pep talks to glasses of water, hoping to purify them with positive thinking before he drinks them. Tom Brady, 45, evangelizes supposedly age-defying supplements, hydration powders and pliability spheres. LeBron James, 38, is said to spend $1.5 million a year on his body to keep Father Time at bay. While most of their contemporaries have retired, all three of these elite athletes remain marvels of fitness. But in the field of modern health science, they’re amateurs compared to Bryan Johnson.

Johnson, 45, is an ultrawealthy software entrepreneur who has more than 30 doctors and health experts monitoring his every bodily function. The team, led by 29-year-old regenerative medicine physician Oliver Zolman, has committed to help reverse the aging process in every one of Johnson’s organs. Zolman and Johnson obsessively read the scientific literature on aging and longevity and use Johnson as a guinea pig for the most promising treatments, tracking the results every way they know how. Getting the program up and running required an investment of several million dollars, including the costs of a medical suite at Johnson’s home in Venice, California. This year, he’s on track to spend at least $2 million on his body. He wants to have the brain, heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, tendons, teeth, skin, hair, bladder, penis and rectum of an 18-year-old.

“The body delivers a certain configuration at age 18,” he says. “This really is an impassioned approach to achieve age 18 everywhere.” Johnson is well aware that this can sound like derangement and that his methods might strike some as biotech-infused snake oil, but he doesn’t much care. “This is expected and fine,” he says of the criticism he’s received.

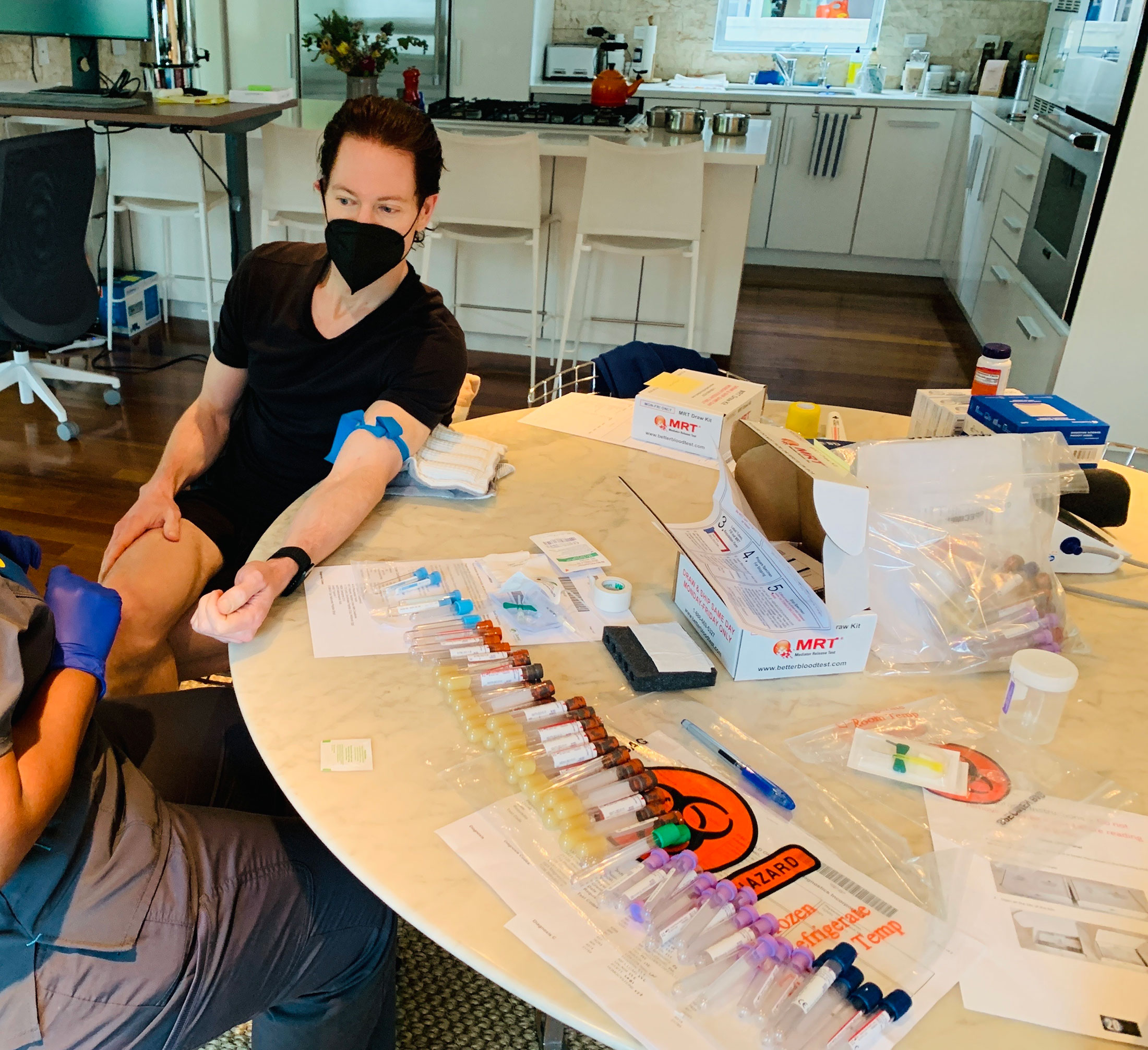

Johnson, Zolman and the team are more than a year into their experiments, which they collectively call Project Blueprint. This includes strict guidelines for Johnson’s diet (1,977 vegan calories a day), exercise (an hour a day, high-intensity three times a week) and sleep (at the same time every night, after two hours wearing glasses that block blue light). In the interest of fine-tuning this program, Johnson constantly monitors his vital signs. Each month, he also endures dozens of medical procedures, some quite extreme and painful, then measures their results with additional blood tests, MRIs, ultrasounds and colonoscopies. “I treat athletes and Hollywood celebrities, and no one is pushing the envelope as much as Bryan,” says Jeff Toll, an internist on the team. All the work, the doctors say, has started to pay off: Johnson’s body is, as they measure it, getting medically younger.

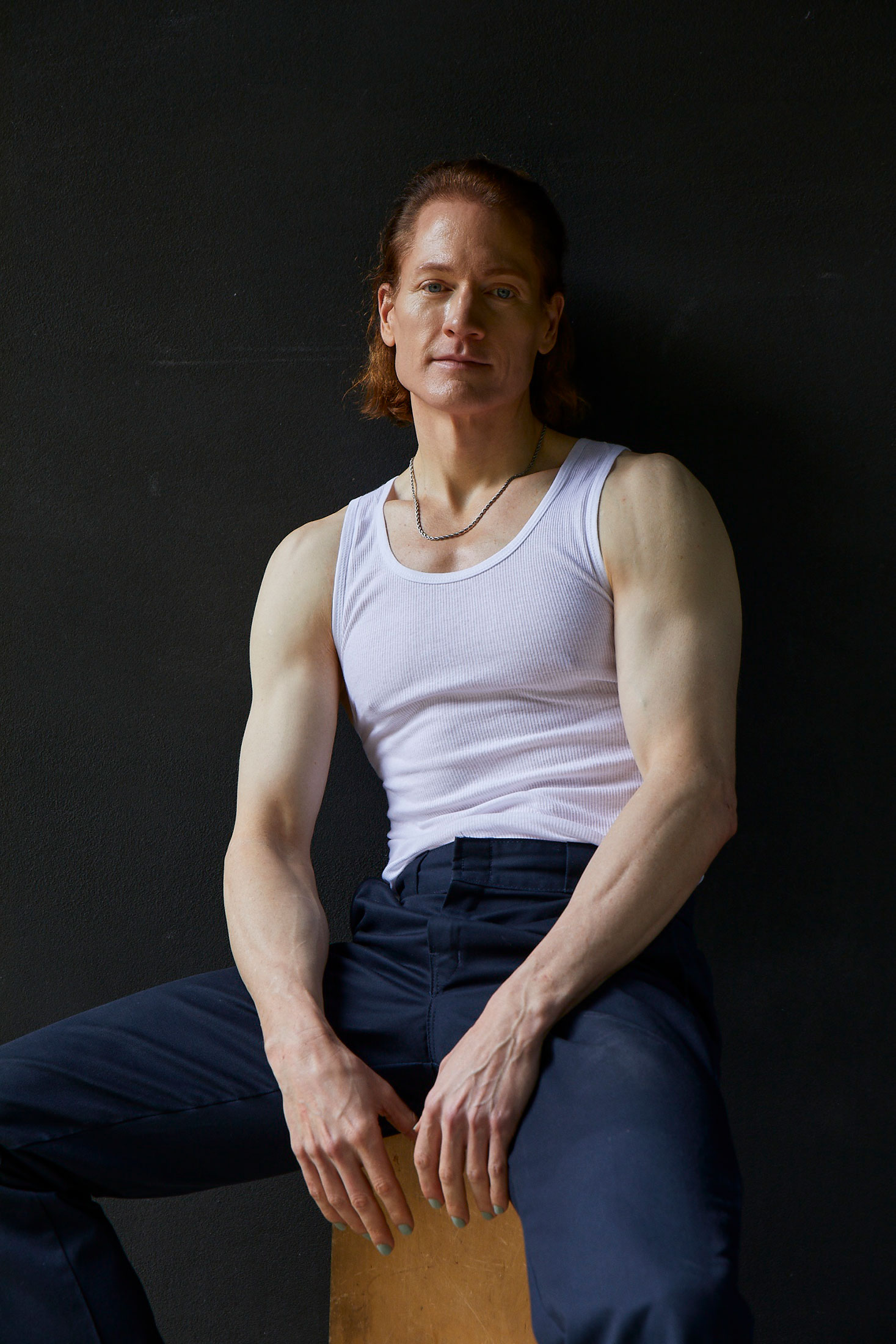

There are some obvious signs that Johnson is at least healthier than most 45-year-olds. The dude is way beyond ripped. His body fat hovers between 5% and 6%, which leaves his muscles and veins on full display. But it’s what has happened inside his body that most excites his doctors. They say his tests show that he’s reduced his overall biological age by at least five years. Their results suggest he has the heart of a 37-year-old, the skin of a 28-year-old and the lung capacity and fitness of an 18-year-old. “All of the markers we are tracking have been improving remarkably,” says Toll.

Zolman, who got his medical degree from King’s College London, is more measured. He stresses that his work with Johnson is just beginning and that they have hundreds of procedures left to explore, including a range of experimental gene therapies. “We have not achieved any remarkable results,” he says. “In Bryan, we have achieved small, reasonable results, and it’s to be expected.”

In Johnson’s mind, however, success is already at hand. While he isn’t the first software developer to grow fixated on living a healthier life, he’s chasing something close to the ne plus ultra version of what tech-industry types call the quantified-self movement. Over the past decade or so, Silicon Valley’s idea of optimizing your innards has mostly taken the form of the occasional exercise or diet fad, from intermittent fasting to Soylent. Johnson’s pitch is that you have to count a lot more than your steps to get a clear picture of what’s best for your body. “What I do may sound extreme, but I’m trying to prove that self-harm and decay are not inevitable,” he says. In conveying the lessons of his unorthodox lifestyle to the rest of us, he’s also counting on a strategy that’s well known in the software business: making it feel, as much as it can, like a game.

In his 30s, Johnson created a payment processing company called Braintree Payment Solutions LLC. It was a massive success, but the long hours and stress left him overweight and deeply depressed, bordering on suicidal. He sold the business to EBay Inc. in 2013 for $800 million in cash, then began a long journey to sort himself out. This included learning more about his biology, an obsession that made its way into his work. He founded a biotech-focused venture firm called OS Fund and then, in 2016, a company called Kernel, which makes helmets that analyze brain activity to learn more about the mind’s inner workings. Researchers are currently using the helmets to try to quantify the impacts of meditation and hallucinogens and find ways to lessen chronic pain. By this time, Johnson had begun tinkering with his body: altering his diet, taking loads of supplements, snorting the occasional vial of stem cells.

I wrote about Kernel (and these early health experiments) for Bloomberg Businessweek in 2021, and I’ve followed Johnson’s physical and mental transformations for a few years now. Throughout, he’s insisted that people don’t have the most important information they need to live healthy lives—that seeing the data in black and white can help people break destructive habits. “You can look at your body and your situation and turn it over to willpower,” he says. “And, like, good luck.” Forcing himself to abide by Blueprint has taken late-night binges (of pizza, booze, whatever) off the table, and all the testing and tweaking has given him confidence that he’s doing as right by his body as he can.

Zolman, a generation younger than Johnson, has experienced his own kind of medical wakeup call. In 2012, his first year of med school in London, Zolman hurt his back playing basketball. The injury proved bad enough that for about a year he struggled to walk properly and sometimes had to use a wheelchair after visits to the hospital. The doctors he met with couldn’t seem to fix things, so he started doing his own research and developing his own physical therapy program, including deep-tissue massages across his legs, glutes, lower back, abs and pelvis. “As soon as I did that,” he says, “boom, I could walk.”

This could sound like the start of any TikToking quack’s sales pitch for enlightenment juice or liver bedazzlers, but Zolman, who isn’t shy about listing his academic achievements, finished his medical degree with honors in 2019. Soon after, he began studying any and all clinical research he thought might help him live healthier for longer.

Zolman is convinced that progress in the field of longevity requires a more concerted pursuit of medicines and therapies that seem in any way promising. Out on the edges of medical science, he argues, there must be better outcomes than the ones we grudgingly accept. In 2021 he opened a firm, 20one Consulting Ltd., in Cambridge, England. “My goal is to prove through biostatistics a reduction of aging of 25% across all 78 organs by 2030,” he says. “It’s an extremely hard and crazy idea.” For beginners, his treatment, offered on a sliding scale, focuses on the basics of improving diet and exercise. More expensive programs, which top out at $1,000 an hour for people in Johnson’s bracket, include lots of testing, therapies and health-aid devices. (He doesn’t charge if the patient doesn’t see results.) Johnson, though, is the only client going this hard.

In Cambridge, Zolman spends much of his time reading research papers and synthesizing their findings into something Johnson can try. “There is no person in the world who is 45 chronologically but 35 in every organ,” Zolman says. “If we can eventually prove clinically and statistically that Bryan has made that change, then it will be such a large effect size that it will have to be causative of the intervention and beyond what’s genetically possible.”

To determine that kind of progress, Zolman says, he keeps track of 10 or more different measurements for each of a patient’s organs. With the brain, for example, he uses a range of MRIs and ultrasounds to track blood flow, tissue volume, scarring, swelling, and plaque growth in the cerebrum, ventricles, midbrain, cerebellum, pituitary and brainstem, and supplements those measurements with cognitive ability tests and blood draws. Configuring the tests, let alone performing them, can be an arduous exercise, because much of the required hardware is usually found only at research institutions.

While he’s effusive and optimistic about his program, Zolman also tries to strike the tone of a realist. He concedes that it will take years to know if he’s chasing the right things and just how well any of this works.

Each morning starting at 5 a.m., Johnson takes two dozen supplements and medicines. There’s lycopene for artery and skin health; metformin to prevent bowel polyps; turmeric, black pepper and ginger root for liver enzymes and to reduce inflammation; zinc to supplement his vegan diet; and a microdose of lithium for, he says, brain health. Then there’s an hourlong workout, consisting of 25 different exercises, and a green juice packed with creatine, cocoa flavanols, collagen peptides and other goodies. Throughout the day, he eats some solid-ish health food (we’ll get there), with the recipes tweaked based on the results of his latest tests. After eating, Johnson brushes, Waterpiks and flosses before rinsing with tea-tree oil and applying an antioxidant gel. His doctors say he has the gum inflammation of a 17-year-old.

There’s a regimen and series of measurements for every last part of Johnson’s body. He’s taken 33,537 images of his bowels, discovered that his eyelashes are shorter than average and probed the thickness of his carotid artery. He blasts his pelvic floor with electromagnetic pulses to improve muscle tone in hard-to-reach places and has a device that counts the number of his nighttime erections. Of late, he’s been presenting as a teenager in that regard, as well.

Daily, he measures his weight, body mass index and body fat, and he monitors his waking body temperature, blood glucose, heart-rate variations and oxygen levels while sleeping. He’s also undergoing a fairly constant stream of blood, stool and urine tests as well as whole-body MRIs and ultrasounds, plus regular tests aimed more specifically at his kidneys, prostate, thyroid and nervous system.

To repair sun damage to his skin, Johnson applies seven daily creams and gets weekly acid peels and laser therapy, and he’s begun staying out of the sun. To improve hearing in his left ear (which suffered from childhood hunting trips in Utah), he does sound therapy, which tests the limits of the frequencies he can hear and then produces inaudible sounds that stimulate the cells in his ear and brain. (Clinical studies performed at Stanford University and elsewhere have concluded that this can help the average person improve their hearing by at least 10 decibels, a significant margin.) He has, however, rejected many of the internet’s favorite health fads, including resveratrol, ice baths and high doses of testosterone.

Doctors on his team help with the scans and tests, read the results and offer advice on what’s safe and what might be dangerous. At one point, Johnson’s body fat had fallen to 3%, which threatened the healthy functioning of his heart. His team recommended tweaks to his diet, including eating more throughout the day instead of consuming all of his calories at breakfast.

Johnson’s lifestyle isn’t for me. In September, shortly before I walked up to his door in Venice for dinner, he texted to warn me that he’d just had some fat injected into his face and seemed to be suffering from an allergic reaction to the excruciating procedure. As a result, he said, he might look a little weird.

He was not wrong.

When he opened the door, I could barely recognize him. His face was so puffed up it looked like he’d spent the afternoon chugging bee venom. Stranger still, his pale skin was glowing, absent of most of the flaws that accompany middle age. He could have been mistaken for a big, swollen porcelain doll.

The procedure, he said, wasn’t the usual Hollywood look-younger filler. It was the first in a series of injections to build a “fat scaffolding” in his face that would produce genuine, young-person fat cells. “Filler is just patching over something,” Johnson said. “It will take a few months for the fat scaffold to build, but then, as I regenerate, it will actually create fat on its own. If I do an MRI or multispectral imaging, then hopefully it will show that I’m identical to an 18-year-old again.” Usually, the early adopters of this procedure harvest the fat from other parts of a patient’s body, but Johnson, who doesn’t have the fat to spare, received his from an undisclosed donor.

This treatment struck me as largely cosmetic. (Johnson also dyes his hair.) And, Zolman notes, there’s little to no evidence that having a fatter, more youthful face or luscious red hair offer clinical benefits on their own. “But, if you do this at the whole-body level, it becomes clinically relevant,” Zolman says. “If you restore young fat-level distribution throughout the whole body, you’re going to have less toxic compounds being secreted and affecting the rest of the body and you’re going to have things like better heat control. If you had no fat, you’d be f---ing dead. If you had no skin, you’d be f---ing dead. These are not aesthetic organs.”

As we talked about Blueprint, Johnson prepared dinner for me, a sample of his typical fare. On the yum side, I was given something called nutty pudding, which consisted of almond milk, macadamia nuts, walnuts, flaxseed, half a Brazil nut, sunflower lecithin, cinnamon, cherries, blueberries, raspberries and pomegranate juice. Delicious. On the yuck side, I also had to eat a mound of vegetables that had been pureed into a gray-brown goop. Once upon a time, it consisted of black lentils, broccoli, cauliflower, mushrooms, garlic, ginger root, lime, cumin, apple cider vinegar, hemp seeds and olive oil, all of which sound fine on their own. But when put together and blended, it felt and tasted like dirt paste.

For dessert, we had chocolate, but not just any chocolate. “With Blueprint, there are layers,” Johnson said. “You can say, ‘Chocolate is good for you.’ Then the next layer is ‘Dark chocolate is better for you.’ And then there is this Dutching process that people sometimes do to chocolate where they alkalize it to take away the bitterness, but it ruins much of the value. So, you want non-Dutched dark chocolate, and you want some that has been tested for heavy metals. And then you want chocolate from the regions of the world that have the highest concentration of polyphenols, which is what you’re trying to get. Unless you’re looking at that fifth layer of polyphenol concentration, you’re really getting very little benefit.”

The lifestyle seems exhausting, but Johnson revels in it, as does his 17-year-old son, Talmage. As our dinner kicked off, Talmage came into the house after a workout. For a moment, he was taken aback at his dad’s swollen face. Then he let out a chuckle, as if he’d seen this type of thing before. Talmage prepared his own specialized dinner alongside us and said he’s adopted some, but not all, of his dad’s practices. For one, he doesn’t do the vegetable sludge, preferring his veggies raw or sautéed.

After dinner, father and son watched as I inserted my arm into a cardiac health monitor on Johnson’s kitchen island. The machine buzzed and whirred for a few seconds, then reported back that my ticker—at least by one measure—wasn’t that far off Johnson’s. It felt like a small victory for paunchy 45-year-old Scotch lovers everywhere.

Johnson has heard his share of criticism from people who’ve accused him of having an eating or psychological disorder or of being a delusional health zealot going about life in the most boring, restrictive way possible. The handful of doctors I’ve interviewed on Johnson’s team all say he’s breaking ground in the field of longevity and probably extending his life, but even they have questions about whether their conclusions will apply to the rest of us. “I think what he’s doing is impressive, and he has personally challenged me to be better,” says Kristin Dittmar, an interventional oncologist. “What he does is also essentially a full-time job.” She also stresses that cancer, her specialty, has genetic components that no cutting-edge science, let alone juices or creams, can yet beat.

One way to pass his gains along to others, Johnson says, might be radical transparency. He has a website where he posts his entire course of treatment and all his test results. And, now, he’s launching another site, Rejuvenation Olympics, that encourages fellow travelers to do the same. The idea is to move away from the latest fads in favor of more rigorous medical science and a dash of competition. The more popular this type of lifestyle becomes, the cheaper and more readily available some of the procedures Johnson tries might be. “If you say that you want to live forever or defeat aging, that’s bad—it’s a rich person thing,” Johnson says. “If it’s more akin to a professional sport, it’s entertainment. It has the virtues of establishing standards and protocols. It benefits everyone in a systemic way.”

For a hint at the size of the early adopter demographic, there’s the blood test offered by a company called TruDiagnostic LLC, which tries to assess a person’s rate of aging by looking at whether various genes are functioning at hundreds of thousands of points across their genetic code. Of the roughly 20,000 people who’ve taken the test in the three years it’s been on the market, about 1,750 have repeated it over years to track their battles against aging. The company says that within that group, Johnson has reduced his biological age the most.

It’s easy to imagine how a coterie of Johnson wannabes experimenting with ever-riskier procedures could go horribly wrong. More likely, most people will find Johnson’s lifestyle impossible or absurd. Some researchers and health aficionados who have run across Johnson’s program take particular exception to his promotion of supplements and vitamins that they view as largely useless.

Still, some of the most respected experts who study longevity and aging say the underlying idea of an open forum for the science of life extension is inevitable. “The whole longevity field is transitioning into a much more rigorous, clinical place,” says George Church, the famed Harvard University geneticist, who has stakes in a number of biotech companies. “I think what Bryan is doing is very well-intentioned and probably very important.” He adds: “I also don’t think a lot of this stuff will be all that expensive when the dust settles.”

While Johnson won’t discuss it yet, he’s about to undergo some far more experimental procedures, including gene therapies, according to several of his doctors and advisers. For better or worse, he’s very much dedicating his body to science in the hopes of proving what’s possible for the rest of us. “That’s the beauty of this,” he says. “It’s a new frontier.”

Read next: Biotech Companies Hunt for Cash as VC Funding Dries Up