MBS’s $500 Billion Desert Dream Just Keeps Getting Weirder

Neom, the Saudi crown prince’s urban megaproject, is supposed to have a ski resort, swim lanes for commuters, and “smart” everything. It’s going great—for the consultants.

One day last September, a curious email arrived in Chris Hables Gray’s inbox. An author and self-described anarchist, feminist, and revolutionary, Gray fits right into Santa Cruz, Calif., where he lives. He’s written extensively about genetic engineering and the inevitable rise of cyborgs, attending protests in between for causes such as Black Lives Matter.

While Gray had taken some consulting gigs over the years, he’d never received an offer like this one. The first shock was the money: significantly more than he’d earned from all but one of his books. The second was the task: researching the aesthetics of seminal works of science fiction such as Blade Runner. The biggest surprise, however, was the ultimate client: Mohammed bin Salman, the 36-year-old crown prince of Saudi Arabia.

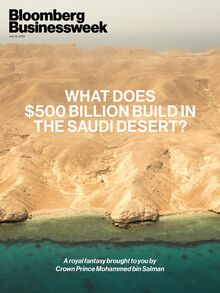

MBS, as he’s known abroad, was in the early stages of one of the largest and most difficult construction projects in history, which involves turning an expanse of desert the size of Belgium into a high-tech city-region called Neom. Starting with a budget of $500 billion, MBS bills Neom as a showpiece that will transform Saudi Arabia’s economy and serve as a testbed for technologies that could revolutionize daily life. And as Gray’s proposed assignment suggested, the crown prince’s vision bears little resemblance to the cities of today. Intrigued, Gray took the job. “If I can be honest with how I see the world, I’ll pretty much put my work out to anyone,” he says.

Gray had signed on to a city-building exercise so ambitious that it verges on the fantastical. An internal Neom “style catalog” viewed by Bloomberg Businessweek includes elevators that somehow fly through the sky, an urban spaceport, and buildings shaped like a double helix, a falcon’s outstretched wings, and a flower in bloom. The chosen site in Saudi Arabia’s far northwest, stretching from the sun-scorched Red Sea coast into craggy mountain badlands, has summer temperatures over 100F and almost no fresh water. Yet, according to MBS and his advisers, it will soon be home to millions of people who’ll live in harmony with the environment, relying on desalination plants and a fully renewable electric grid. They’ll benefit from cutting-edge infrastructure and a regulatory system designed expressly to foster new ideas—as long as those ideas don’t include challenging the authority of MBS. There may even be booze. Neom appears to be one of the crown prince’s highest priorities, and the Saudi state is devoting immense resources to making it a reality.

Yet five years into its development, bringing Neom out of the realm of science fiction is proving a formidable challenge, even for a near-absolute ruler with access to a $620 billion sovereign wealth fund. According to more than 25 current and former employees interviewed for this story, as well as 2,700 pages of internal documents, the project has been plagued by setbacks, many stemming from the difficulty of implementing MBS’s grandiose, ever-changing ideas—and of telling a prince who’s overseen the imprisonment of many of his own family members that his desires can’t be met.

Efforts to relocate the indigenous residents of the Neom site, who’ve lived there for generations, have been turbulent, devolving on one occasion into a gun battle. Dozens of key staff have quit, complaining of a toxic work environment and a culture of wild overspending with few results. And along the way, Neom has become something of a full-employment guarantee for international architects, futurists, and even Hollywood production designers, each taking a cut of Saudi Arabia’s petroleum riches in exchange for work that some strongly suspect will never be used. Few are willing to speak on the record, citing nondisclosure agreements or fear of retribution; at least one former employee who criticized the project was jailed in Saudi Arabia. (He’s since been released.)

It would be unfair to entirely dismiss Neom as an autocrat’s folly. Parts of the plan, such as a $5 billion facility to produce hydrogen for fuel-cell vehicles and other uses, are rooted in current economic realities, and building a global hub almost from scratch isn’t without precedent in the region; even 30 years ago, most of Dubai was empty sand. Since he became Saudi Arabia’s de facto ruler in 2017, MBS has demonstrated a talent for imposing dramatic change, doing away with large swaths of the religious restrictions that used to bind every aspect of daily life. Women are pouring into the workforce, and teenagers are able to dance at sold-out music festivals—events that were previously unimaginable.

Nonetheless, the chaotic trajectory of Neom so far suggests that MBS’s urban dream may never be delivered. The same is true of his broader plans for economic transformation. In the crown prince’s telling, Saudi Arabia will soon be a center of innovation and entrepreneurship, free of the corruption and religious extremism that have long held it back. But to his critics, this promised future is a veneer, a layer of technological gloss over a core of repression, kleptocracy, and—above all—indefinite one-man rule.

“I was not alone in realizing that it was spurious at best,” Andy Wirth, an American hospitality executive who worked on Neom in 2020, says of the project. “The complete absence of being tethered to reality, objectively, is what was demonstrated there.”

MBS introduced Neom at the inaugural Future Investment Initiative, a glitzy conference for international investors held in 2017 at Riyadh’s Ritz-Carlton Hotel—the same hostelry that days later would become a five-star prison for businessmen his government accused of corruption. Everything about Neom, which is a portmanteau combining the Greek word for “new” with mustaqbal, Arabic for “future,” would be cutting-edge. The difference between it and an ordinary city, MBS declared from the stage, would be as stark as the gap between an old Nokia and a sleek smartphone.

In an interview the same day with Bloomberg News, MBS explained that Neom’s most important innovation would be its legal framework. He said that in a place like New York, there’s an inconvenient need for laws to serve citizens as well as the private sector. “But Neom, you have no one there,” he said, omitting mention of the tens of thousands of Saudis then living in the area. As a result, regulations could be based on the desires of investors alone. “Imagine if you are the governor of New York without having any public demands,” MBS said. “How much would you be able to create for the companies and the private sector?”

The idea of an authoritarian polity run for the benefit of international capital had a certain appeal to the Davos class. Steve Schwarzman and Masayoshi Son, the chief executives of Blackstone Inc. and SoftBank Group Corp., respectively, were among the international financiers who endorsed the project. Klaus Kleinfeld, the former CEO of Alcoa Inc., was appointed to lead it. Architects and planners were also interested, seeing a rare chance to shape a metropolis from the ground up—even if some wondered whether the money might be better spent improving existing Saudi cities. Neom looked like a “pace-setter in terms of new kinds of thinking around mobility and energy,” says John Rossant, the chairman of NewCities, a nonprofit focused on urban issues, who joined its advisory board. Its model makes room for blue-sky ideas; some employees say they view the project as a sort of urban skunk works, providing a rare opportunity to test futuristic concepts even if they’re likely to fail.

Although the Neom site was in a region few Saudis have ever visited, MBS made clear that he expected it to become a hub for national life. Within a few months of the Ritz-Carlton announcement, satellite images showed that a series of large buildings was already under construction, surrounded by expanses of greenery that stuck out sharply from the desert. It was a new palace for the crown prince, where he’d soon be spending much of his time.

Less than a year after MBS declared his intentions for Neom, the Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi walked into Saudi Arabia’s consulate in Istanbul and never walked out. A US intelligence assessment found that MBS likely ordered the writer and government critic’s murder; the crown prince denied any involvement. But the ensuing outrage cast a pall over foreign investment in Saudi Arabia, and many businesspeople cut ties with the kingdom—and with Neom. Among others, the British architect Norman Foster, former Y Combinator President Sam Altman, and ex-US Secretary of Energy Ernest Moniz all left the Neom advisory board. MBS was undaunted. At the second gathering of the Future Investment Initiative, held three weeks after Khashoggi was killed, he hosted some of the remaining advisory board members for a late-night audience at his palace. According to Rossant, who was in attendance, MBS described Khashoggi’s death as a “tragedy” that should never have occurred. He also delivered a clear message: Neom would go on no matter what.

It would, however, be an increasingly Saudi-led project. Kleinfeld had lasted less than a year as CEO and was replaced a few months before the Khashoggi murder. His successor, Nadhmi Al-Nasr, came from Saudi Aramco, the state oil company. A chemical engineer by training, Al-Nasr had a reputation at Aramco for executing complicated plans. He’d also learned to navigate the demands and sensitivities of Saudi Arabia’s rulers. And at Neom, understanding the preferences of the man at the top is paramount. “His Royal Highness,” Al-Nasr says, “has been with us, and I am not exaggerating, almost daily.”

Neom’s first major development was planned for Sharma, a modest town of car repair shops and concrete houses scattered around a placid bay. The goal was to create a community inspired by the Côte d’Azur, with an initial population of almost 50,000. To plan it, Neom executives turned to an unusual source, according to internal documents and two former employees: Luca Dini Design & Architecture, an Italian firm that specializes in superyachts. Luca Dini’s designers tweaked and retweaked their proposals with feedback from a committee headed by MBS. The result was a concept called Silver Beach. Instead of mere sand, the seaside would be lined with crushed marble, planners noted, which would shimmer in the sun like silver. Bound by tight deadlines to begin construction, Neom staff and consultants worked overtime for weeks to refine the design, which also included a yacht club, an electric-car racing circuit, and more than 400 mansions, some as large as 100,000 square feet.

Then, in the first quarter of 2019, the project was abruptly shelved, several former employees say. Two of them recall being told that the concept, even with its lustrous seaside, wasn’t imaginative enough for Neom’s leadership. Real estate development can involve considerable trial and error, and many designs never see the light of day. But to the employees, scrapping Silver Beach was part of a pattern of working furiously on ambitious, expensive plans that were quickly abandoned—such as one of Neom’s early initiatives, a $200 billion solar field that was canceled soon after being announced. “If I had to put a bottom line for all the work that I did in this era, it was presentations and PowerPoints that went into the garbage the next week,” says a former manager who worked on Silver Beach. “It was the least productive part of my whole life in terms of doing real things and the most productive in terms of the money I got.”

The work could indeed be phenomenally lucrative. Neom offered tax-free salaries of $700,000 to $900,000 for some senior expatriates—more than 20 times the income of the average Saudi—and a broad range of other perks. With pay packages like that, it had little trouble attracting foreign staff, especially once the initial furor over Khashoggi subsided. Most were required to live on the project site, where Neom had constructed temporary housing—comfortable if basic apartments in the desert, with an army of migrant laborers taking care of food, cleaning, and laundry. Remote work was discouraged during the pandemic; in 2020 the government chartered flights from London to bring Neom staff to Saudi Arabia.

As more of them arrived, foreign employees began describing their experiences with a joke: When you start at Neom, you bring two buckets. The first is to hold all the gold you’ll accumulate, and with so many living expenses taken care of, it will soon grow heavy. The second bucket is for all the shit you take. When that bucket is full, you pick up your bucket of gold and leave. It often doesn’t take long; many people Neom hires last less than a year.

Former employees say one of the chief sources of aggravation is Al-Nasr, whom they describe as having a volcanic temper. Several recall him openly berating subordinates, sometimes issuing threats unlike anything they’d experienced in their careers. In one particularly tense moment, after two e-sports companies canceled partnerships with Neom, citing human-rights concerns, Al-Nasr said he’d pull out a gun and start shooting if he wasn’t told who was to blame, according to two witnesses to the exchange. Al-Nasr disputes these accounts. “Not anyone can stand the pressure of the demands of the day, and there are people who leave because it’s more demanding than anything they have done before,” he says.

Among the misdeeds most likely to anger Al-Nasr, the former employees say, was failing to spend enough money. Three of them described Al-Nasr keeping a diagram showing which department heads were disbursing less than their budgets allowed, which the ex-staff half-seriously referred to as a “wall of shame.” There were few constraints on hiring outside consultants—both McKinsey & Co. and Boston Consulting Group Inc. have worked extensively on Neom—and some plans were developed so fast that the firms hired to assess them would provide cost estimates with 40% buffers. One former senior manager says he was so disturbed by what he saw as financial waste that it kept him up at night. (In response, Al-Nasr says that “we don’t do it this way” and that Neom evaluates employees based on their progress implementing plans, not how much they spend.)

Wirth, the American hospitality executive, was hired to work on a particularly expensive project: a Neom ski resort. The idea is slightly less absurd than it sounds. Temperatures sometimes dip below freezing on the region’s higher mountaintops; with enough snow-making equipment, it could be possible to facilitate a winter ski season. But Wirth soon grew alarmed by the environmental implications. The resort plans called for building an artificial lake, which would require blowing up large portions of the landscape. The Vault, an adjacent hotel and residential development, would occupy a man-made canyon, essentially “a massive open-pit mine,” Wirth says. It was a landscape that might have been lifted from Foundation, an Apple TV+ series set thousands of years in the future that MBS has said he enjoys. (Loosely based on novels by Isaac Asimov, it tells the story of a mathematician’s quest to protect human knowledge from the collapse of a dying galactic empire, whose three genetically identical monarchs live in a sprawling palace while their subjects toil below ground.) “We couldn’t even estimate the build cost,” Wirth says. “We were hanging buildings on the side of cliffs, and we didn’t even know the geology.” He decided faster than most that his No. 2 bucket was overflowing. Wirth resigned in August 2020, five months into the job.

The main residential camp for Neom’s 2,000 employees is tucked among rocky hills 2 miles from the coast. To enter, I had to pass two checkpoints manned by private security guards. My face was also scanned by machinery bearing the logo of Zhejiang Dahua Technology Co., a company accused by activists of helping the Chinese government surveil Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

Past the barbed-wire fence, Neom Community 1 unfolds in a series of neat lawns and identical white homes. Each is about the size of a shipping container, identified by a series of letters and numbers—Block 15, C-83, for example. Meals are served in a central dining hall, and employees zip between buildings on electric scooters. The overall aesthetic might be described as a cross between a Google campus and a minimum-security prison, albeit one with a small population of children: Community 1 has a school, and some employees have moved their families in.

Neom’s marketing is everywhere. One poster in an office building instructs employees to embody a “champion mindset,” emphasized with inspirational quotations from MBS and Nelson Mandela. (The poster gives them equal billing.) That means maintaining “an unshakable belief in yourself and Neom, challenging the status quo, demonstrating an innovative ethos that enables everyone to seek and become a CATALYST FOR CHANGE.”

Many staffers seem to have genuinely bought into that message. Jan Paterson, a British-Canadian who heads planning for Neom’s “sports sector,” says she wants her grandchildren to grow up in the city, which she hopes will be the most physically active urban center in the world. Three years in, she’s one of the longest-serving employees. “I joined because, in my working career, no one has ever said, ‘Do you fancy setting up a semi-autonomous state using your passion as a tool for positive social change?’ ” Paterson explains. “It’s as simple as that.” Her eyes light up as she describes an ideal day in the Neom of the future. Imagine a sixth grader, she says. When he wakes up, his home will scan his metabolism. Because he had too much sugar the night before, the refrigerator will suggest porridge instead of the granola bar he wanted. Outside he’ll find a swim lane instead of a bus stop. Carrying a waterproof backpack, he’ll breaststroke the whole way to school. Paterson actually means this; Neom says it’s considering an idea for canals filled with swimmable water, creating a novel aquatic commuting option. If all goes well, she says, residents can expect an extra 10 years of “healthy life expectancy.”

Living and working in their camp, Neom executives have little contact with the indigenous inhabitants of Tabuk, as the broader area is called. Its coastline has long been one of Saudi Arabia’s more neglected territories; some towns weren’t hooked up to the electric grid until the 1980s. Many of its people are members of the Huwaitat, an historically nomadic tribe, now settled in the region where Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Egypt meet. From the start, there was no place for them in Neom’s plans, and thousands were told in early 2020 that the state would require their land.

As officials went house to house months later, surveying the properties to be cleared out, a man named Abdulraheem Al Huwaity greeted them angrily. He began recording a series of videos with his phone, which soon went viral. His wiry beard streaked with gray, Al Huwaity faced the camera head on, speaking in a steady voice as he accused the government of intimidating residents into signing over their homes. He also broke almost every taboo of Saudi political speech. MBS’s reign amounted to “rule by children,” he said, and the government’s clerics were “silent cowards.” Al Huwaity declared he was waiting for the authorities to arrest or kill him. The measure of a life, he said, isn’t time spent on Earth; rather, “a stand of one day can equal 90 years.” In mid-April 2020 heavily armed police arrived at his house and a gunfight ensued. When it ended, Al Huwaity was dead and two officers injured. The government said he had weapons in his home and had opened fire, ignoring demands that he surrender.

After Al Huwaity’s death, officials expanded the compensation packages provided to removed residents, promising to grant them land elsewhere in the region. For larger properties, residents say, the payments can reach 1 million riyals ($266,000), though the owner of a simple home might receive just 100,000 riyals—less than the monthly salary of some Neom employees. Neom is also offering training programs for local youth and funding a scholarship program that sends students from Tabuk to the US, after which they receive jobs at the project. “We want to make sure the locals here feel the value of Neom,” Al-Nasr says.

The town of Sharma, where Silver Beach was supposed to be, has been flattened, along with Alkhurayba, where Al Huwaity lived. On a recent visit, a lyric from an Arabic love song had been spray-painted on one of the few walls still standing: “He’s unjust, but?” The word for “unjust,” dhalim, can also mean “tyrant.” One Huwaitat man, who asked not to be identified because he fears retaliation, says he resisted relocation at first. But after Al Huwaity was killed and the authorities cut off the electricity and closed the schools, he realized he had no choice. He’s waiting for his compensation payment. “What can we do?” he asks. “We want to live.”

In January 2021, MBS appeared on Saudi television to introduce Neom’s most far-fetched element yet, a “civilizational revolution” called the Line. A “linear city” 100 miles long, it would generate zero carbon emissions. Its 1 million residents would occupy a car-free surface layer, with no one more than five minutes’ walk from essential amenities; utility corridors and high-speed trains would be hidden underground, along with infrastructure for moving freight.

The concept carried echoes of an idea originated in the 1960s by Superstudio, an Italian architectural collective, for a structure so enormous it would wrap around the entire planet. This “Continuous Monument” was never a real building proposal; it was intended as a critique of excessive urbanization and of the modernist megaprojects then in vogue. One of Superstudio’s last surviving members, when asked about the Line by the New York Times, dryly noted that “seeing the dystopias of your own imagination being created is not the best thing you could wish for.”

Within Neom, the Line was being overseen by Antoni Vives, the head of urban development. A former deputy mayor of Barcelona, Vives had been hired in 2018 and quickly became one of Al-Nasr’s closest allies. But two weeks after the plan was announced, a judge in Vives’s home country found him guilty of charges of malfeasance relating to his time as an official, according to El Pais newspaper. Vives was sentenced to two years in prison, which was reduced to community service. He returned to Neom soon after. (Vives didn’t respond to requests for comment; Al-Nasr says that Neom doesn’t penalize employees for “their own country’s business or politics” and that Vives is “an honest person, putting his time and his life to this job.”)

Neom staff are still working nonstop to deliver the Line and to move forward with other projects. Early construction has started on the mountain resort that so alarmed Wirth, which will require the removal of more than 20 million tons of rock—three times the weight of Hoover Dam. At Oxagon, a vast industrial zone to be built partly on pontoonlike structures floating in the Red Sea, workers are digging the foundations of a hydrogen plant, while cranes swing back and forth over an almost finished data center. And according to Al-Nasr, Neom’s legal and political framework is nearly complete. An entity called the Neom Authority will govern the region, its head appointed by the Saudi king—almost certainly MBS, once he succeeds his 86-year-old father, King Salman. It may be demarcated from the rest of the country by a “digital border,” allowing entry only to those with authorization. Residents will be represented by an advisory body, though it’s not yet clear whether its members will be elected.

To Neom’s backers, such detailed planning is all part of a serious effort to create a hypermodern city—a bold initiative but not a ridiculous one. Ali Shihabi, a commentator close to the government who sits on the Neom advisory board, says he divides its components into two categories: those that could make a realistic near-term difference to Saudi Arabia, such as improved desalination technology, and those that he concedes are more “aspirational.” Neom “has a huge amount of research and thought and strategy and substance behind it,” he says.

At the same time, Neom executives and their array of consultants continue to generate yet more ideas, some of them informed directly by Hollywood. Over the past several years, Neom has commissioned work from Olivier Pron, a designer who helped create the look of the Guardians of the Galaxy films, and Nathan Crowley, who’s known for his work on the Dark Knight trilogy. It’s also hired Jeff Julian, a futurist with credits on World War Z and I Am Legend, movies that depict a zombie apocalypse and the aftermath of a pandemic that’s wiped out most of humanity, respectively.

Gray, the Santa Cruz author, was hired to help conceive a high-end tourism zone called the Gulf of Aqaba, which internal documents say will feature luxurious homes, marinas, nightclubs, and a “destination boarding school.” MBS told its designers that he liked the aesthetic of “cyberpunk,” a sci-fi subgenre that typically depicts a dark, tech-infused future with a seedy underworld—think William Gibson’s novel Neuromancer or the Keanu Reeves vehicle Johnny Mnemonic (also based on a book by Gibson). “I was a little surprised to hear that the prince was very interested in science fiction, but many people are, of all sorts of political persuasions,” Gray says. He and a team of other consultants were soon working long hours to research the aesthetics and implied culture of cyberpunk’s many iterations, which fed into a taxonomy of science fiction atmospheres that Neom employees were developing.

An internal document from this exercise listed 37 options, arranged alphabetically from “Alien Invasion” to “Utopia.” After input from a panel of experts, 13 advanced to the next phase of consideration—almost all of them cyberpunk-related in some way. These were divided further into “backward-looking” and “forward-looking” categories and laid out on a spectrum from dystopian to utopian. Each was analyzed in depth, with Neom staff interrogating their values. (“The big question biopunk asks is, Where does one stop being human?”) Next they ranked the concepts on a matrix of factors, including whether they had a “strong architectural component” and their alignment with Neom’s goals. Two guiding philosophies for the Gulf of Aqaba came out on top: “solarpunk,” depicting a future where environmental challenges have largely been solved, and “post-cyberpunk.” The latter, the document said, takes a relatively optimistic view of the world to come, with clean edges, slim skyscrapers, and sleek flying cars. It identified the best example of the style as Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther—coincidentally, the first movie shown when MBS allowed Saudi cinemas to reopen after a decades-long ban.

It remains to be seen, of course, whether ideas like the Gulf of Aqaba will survive contact with financial and physical reality. Almost immediately after the Line was unveiled, Neom executives discovered just how challenging the project would be. One major problem, an internal progress report explained, was building the underground layer that’s supposed to contain transportation and logistics facilities. There would be “abnormal upfront infrastructure/utilities costs resulting from linear design,” it said. According to several ex-employees, the original concept for a series of interconnected low-rise communities gradually evolved into an idea for two parallel mega-structures, as tall as the Empire State Building, that would extend horizontally for dozens of miles. Using back-of-the-envelope calculations, a former Neom planner estimated they could cost $1 trillion to build. Neom isn’t discussing any of this publicly, even as crews start early work on the site and designers refine plans for a half-mile-long prototype. “What we will present when we are ready will be revolutionary,” Al-Nasr says.

At a recent art biennale in Riyadh, renderings of Superstudio’s Continuous Monument hung on the wall, showing a linear structure swallowing the whole world. The caption invited viewers to “imagine a near future in which all architecture will be created with a single act.” The idea stayed in my mind long after leaving Neom, where I flew in a helicopter over the spot where the Line is supposed to begin. From far above, the construction vehicles churning the ground looked like toys. There was already a faint but unmistakable slash—one man’s will carved into the desert. It traced inland from the sea toward the mountains, then disappeared in the haze. —With Matthew Martin, Ben Bartenstein, and Rodrigo Orihuela