This is your last free member-only story this month.

We Are Absolutely Horrible At Stopping Financial Scams

We’ve failed to protect people again and again.

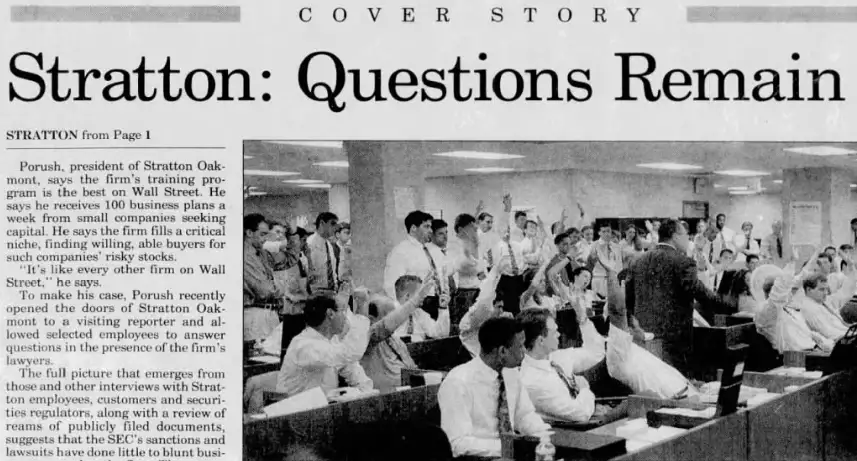

Stratton Oakmont (of Wolf of Wall Street fame) was not nearly as glamorous or crafty as they like to think they were. In fact, their crimes were committed in an almost laughably stupid and obvious manner from an office located behind a loading dock in an industrial area. Their brazenness would be awe-inspiring if not for one thing: they could get away with it for years, and the principals almost certainly knew as much.

The insider trading and pump-and-dump schemes were evident almost immediately after the firm’s founding. Newspapers all over the country had stories about the little boiler room. SEC presence began as early as 1991, but the firm continued to scam people for another half-decade. Their insider trading was publicly disclosed in filings for anyone who cared to view it. Even reporters with little-to-no financial background managed to put together the trail in local papers. No one cared.

Why be smart or put in the work when you know you’re just going to get a slap on the wrist? More often than not you’d never be caught at all. Bernie Madoff’s right-hand man started working for him in 1975 and told investigators that Madoff’s scam had been running for as long as he could possibly remember. It seems the stunningly consistent returns didn’t raise any eyebrows, at least not where it counted. Despite numerous complaints and half-completed investigations, Madoff was allowed to continue running his scheme for decades.

Enron was named one of America’s most innovative companies (I suppose in a sense that was true) for six straight years, including the one where they declared bankruptcy. Their fraudulent accounting was ongoing for at least four of those six “innovative years” and, in all likelihood, much longer. Short sellers noted discrepancies in the accounting years beforehand and began betting against the stock. It was there for all to see if we wanted to look.

That’s not even touching on all the imaginary valuations drummed up during the financial crisis or barely-legal tools like the CDOs (now named BTOs to dodge regulations) that almost toppled the world economy in its entirety. We’re just downright horrible at stopping predatory white-collar practices. People are dropping to the floor all around us from smoke inhalation, and our regulators can’t seem to admit there’s a fire.

So are global white-collar laws too narrow, too difficult to prove, or just too loose in enforcement? Are regulators toothless, ineffective, or both? How much of this should fall under the “personal responsibility” category? Let’s look.

Enforcement

Before digging in, I should note that while this problem seems to be exceptionally pronounced in America, it is not a uniquely American issue. The FCA in the UK and CSA in Canada have also faced criticism for a light touch with regard to regulations at various times. Neither has had as many glaring, high-profile mistakes as the SEC, but they’ve each had their own missteps at times.

That said, some less developed nations have such rampant corruption and so many bigger problems to worry about that financial crime laws are rarely enforced, assuming they even exist at all. In those same countries, however, few in the general population have worries about defending their 401k or other such developed world problems, so laws of this kind likely aren’t a top concern anyway.

For the rest of us, though, we have to wonder why our laws preventing financial crimes are so…useless. I mean, sure, they’re there, but between loose enforcement, poor investigative capability, and lax punishment, they don’t really stop or even deter predatory behavior. Which raises another question: why even have something on the books that will never be utilized?

Financial crimes, such as insider trading, have wide sentencing guidelines in the United States. For those of you who have an abundance of time, you can read up on them here. In short, “general economic crimes” are supposed to be punished on a sort-of sliding scale of severity depending on the offender’s “gain” in committing the crime. However, since “gain” is not defined, this basically opens the door up to anything. Could be 20 years, could be probation.

The fact is, though, that our general financial crimes rarely make it to that stage in many developed countries. Much like mass shootings, we discover after a major incident that the guilty party had been subject to numerous investigations, complaints, and other actions but that no measures were taken to stop the individual or prevent future abuses.

At Stratton Oakmont, as an example, the SEC was a constant presence. It did nothing to stop their pump-and-dump schemes, which continued to be conducted in an entirely obvious manner. The SEC would assign some industry bans or suspensions, which would result in a shuffling of positions by the principals or share transfers to LLCs and relatives of the banned traders. This would then “technically” comply with the SEC’s restrictions and be allowed to continue.

In some cases, offenders were just told they could no longer hold “supervisory” roles but were free to continue doing what they were doing (Newsday, Nassau Edition — July 1995.) As a result, arbitrary title changes and outside equity transfers were all that were required to continue defrauding investors. Madoff’s story is even worse, but that’s been covered extensively in film and other media.

Is it a matter of staffing? Maybe. The SEC has roughly 4,200 employees. That’s a misleading number, however. They field 30–35,000 complaints in a given year. While each complaint could be reasonably reviewed given the number of employees, the actual investigative arm is much more limited. Recent changes have given a total of 36 individuals subpoena power for records or testimony. Prior to those changes, it was two. Yes, that’s correct. Two people. There are more supervisors at your local McDonald’s than there were people capable of conducting investigations at the SEC.

It goes without saying that more than just those 36 people actually review the documents obtained and determine negligence, malfeasance, or fraud. But issuing and ensuring compliance with a subpoena is a time-consuming process. Having 30,000 complaints ultimately flow through two people to determine if further information is warranted is bound to create bottlenecks and half-completed work.

This is perhaps a part of why investigations stall out. A sense of “I have to clear this s*** off of my desk” versus “I have to dig in and see what’s going on here” can dramatically alter the approach to anything, let alone a time-consuming, in-depth investigation into the minutiae of accounting practices and paper trails. When Bernie Madoff submitted false financial records, he complied with the records request portion of the subpoena. It was up to investigators to validate the information he provided. They never did, and so it wasn’t revealed he had sent an entirely fabricated list of investments.

Our drug war funding of $50 billion is about 2,500% higher than the SEC’s funding of $2 billion. Our priorities are clear, and financial crimes aren’t one of them. The “why” behind that? We can tackle that another time.

Look out for yourself

Waiting for predatory and illegal behavior to leave the market will be a game that never ends. Even with better enforcement, there will always be hucksters out there. Investors have to look out for themselves, which is why keeping a level head is important. The less emotion involved in your finances, the better off you will be.

If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is. Ask crypto investors about that right now. There is no such thing as a completely guaranteed return. If someone is “ensuring” that you’ll have a magical 20% return on your investment — as Stratton Oakmont, Bernie Madoff, and the recently collapsed Terra coin all did — alarm bells should start ringing immediately.

So too should anyone who uses hyperbole and histrionics in their sales pitch. “Invest the money you can’t afford to lose” read one Medium article. Others just reiterate how this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and represents your ticket out of the class trenches and into the 1%. It might be for the pumpers, but you’re on the “dump” side of that equation. Be on guard. Always.

That’ll be cold comfort to those who’ve already lost money on scams, or disadvantaged groups who are more susceptible to them. The elderly, technology-illiterate, and others will always be targets. Unfortunately, our system doesn’t do much to protect them. The rest of us can help out where we can by reporting scams where we see them and hoping for the best.

On some of the more basic, ground-level scams, you can stay on the phone for a while. If you do, the scammers may eventually provide some bank account info for you to send your hard-earned money to. Obviously, don’t do that.

You can, however, pass that account information on to the authorities. Who knows, you might save someone’s grandmother from losing her life savings. At the very least, you’ll have done more than our regulators often do.

Want more articles like this? Subscribe to MOAM’s Friday newsletter here.

This article is for informational purposes only. It should not be considered Financial or Legal Advice. Not all information will be accurate. Consult a financial professional before making any major financial decisions.