6 Months as a Full Time Pancreas

Managing our Son’s Type 1 Diabetes with Multiple Daily Injections and Dexcom G6 Continuous Glucose Monitor

In a previous post, I wrote about my 18 month old son’s (Sam) Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) diagnosis and the first month when we were learning as much as possible and struggling. That post was received with so much love and positivity, I have decided to follow up with a 6 month recap.

Sam has now had diabetes for a quarter of his life (18–24 months). We have spent these first 6 months learning to be Sam’s pancreas using Multiple Daily Injections (MDI) and the Dexcom G6 Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM). This post is about what we are doing and what we are focused on. It will hopefully be helpful for people in a similar situation and to serve as a reminder to ourselves how far we have come managing T1D.

Obligatory: nothing here is medical advice.

The Dark Days: MDI + finger pricks

After leaving the hospital, we managed Sam’s T1D with Multiple Daily Injections (MDI), a blood glucose meter (caresens dual) and an oncall nurse helping us. This was it for 2 weeks, from 21st Jan until 4th Feb. It did not go well.

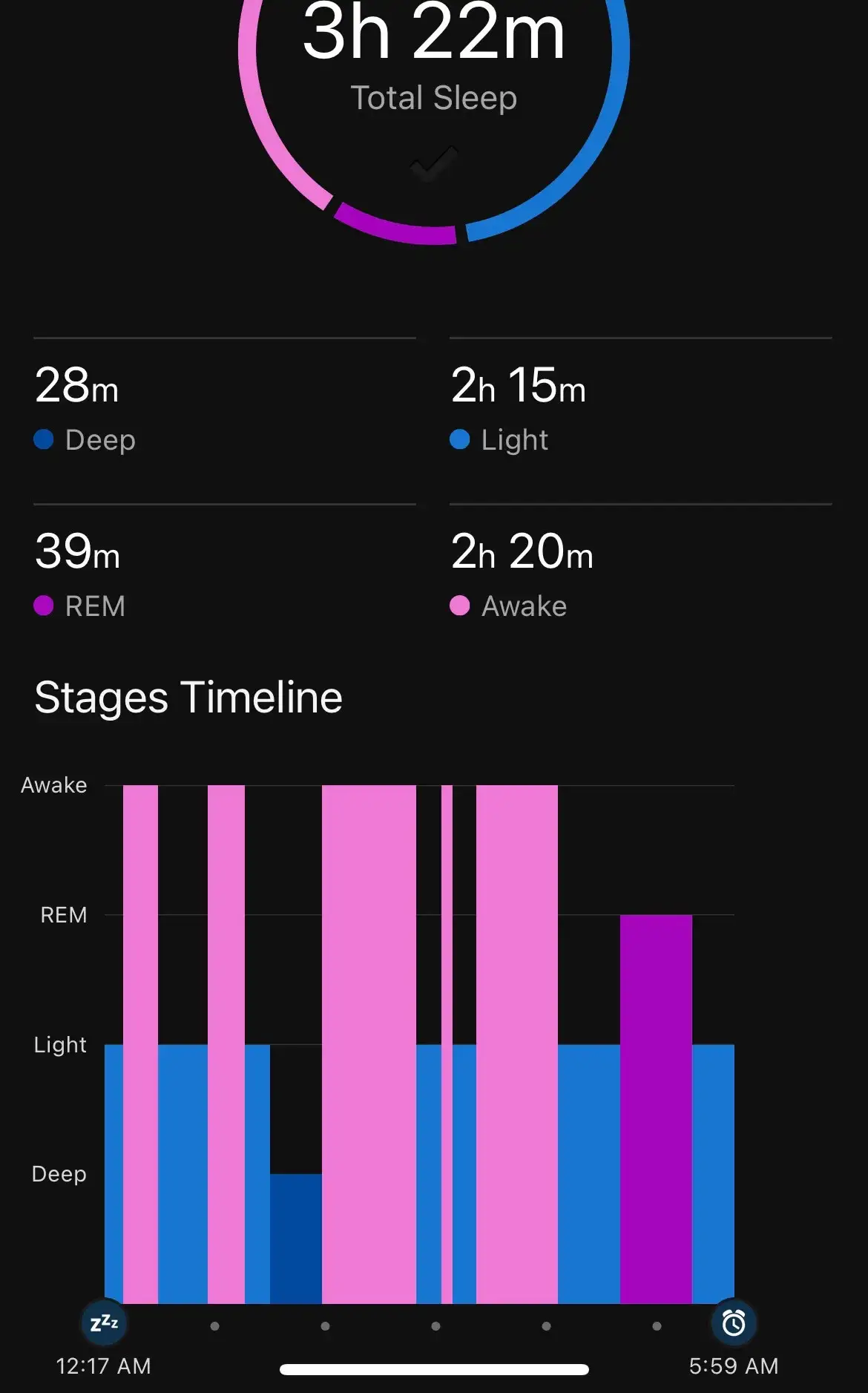

Here is what the final week looked like:

The insulin injections (left) are P for protaphane and N for Novorapid. The Blood Glucose Level (BGL) readings (right) are from a meter and manual finger prick test.

A quick BGL reminder anything under 4 is low and under 3 is very low and can result in hypoglycemic seizure and death. Anything over 10 is high, over 15 is very high and, if untreated, can result in diabeteic ketoacidosis and death. mmol/L is the unit we use.

You can see from this page that:

- Sam was getting about 5 insulin injections and 10 BGL tests per day. Each injection and test requires stabbing him (a little).

- Sam had wild readings ranging from urgent lows (2.9) to massive highs (20.3) coming out of nowhere and remaining undetected for hours.

- We were so afraid of lows that we over reacted to every low with too many carbs. Also, we under reacted to highs with not enough insulin.

- We were stressed every time we gave him food or insulin. Feeling afraid to feed your child is not good for anyone.

The squashed columns on the right where I would test him multiple times overnight. The nighttime routine was:

- do a BGL test at 10pm and 2am. A BGL test involved stabbing his finger to draw blood.

- If low I would give him some sugar. If very high I would give him insulin (more stabbing).

- If I gave him sugar or insulin, he would need a follow up test in about an hour to make sure it is working.

- The night finishes when Sam wakes up at 5am(!) wanting to play.

All the testing, treating, retesting and stabbing would result in nights like:

Manage T1D with a manual glucose meter is hard. We were really trying and still getting bad and confusing results. We were always afraid that he would go low without detection and the worst possibilities were constantly playing in our minds. This was not sustainable.

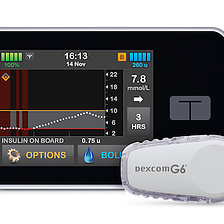

The Less Dark Days: MDI + Dexcom G6

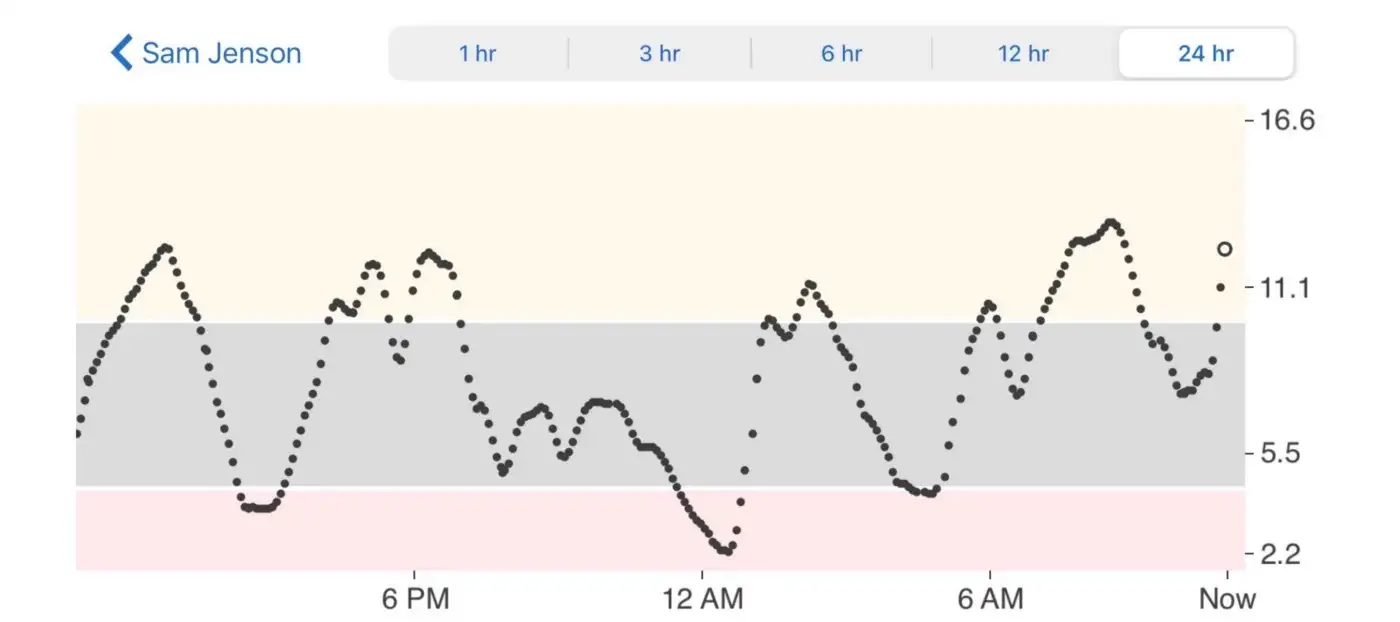

Dexcom G6 Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) changed everything. I cannot overstate how much better managing diabetes is with a CGM.

With a manual blood glucose meter we would have 10 BGL readings a day, with a G6 we get 288(!); a reading every 5 minutes, 24/7. Also, we only have to stab Sam once every 10 days to replace the CGM, so that is 2880 times less stabs than manual testing.

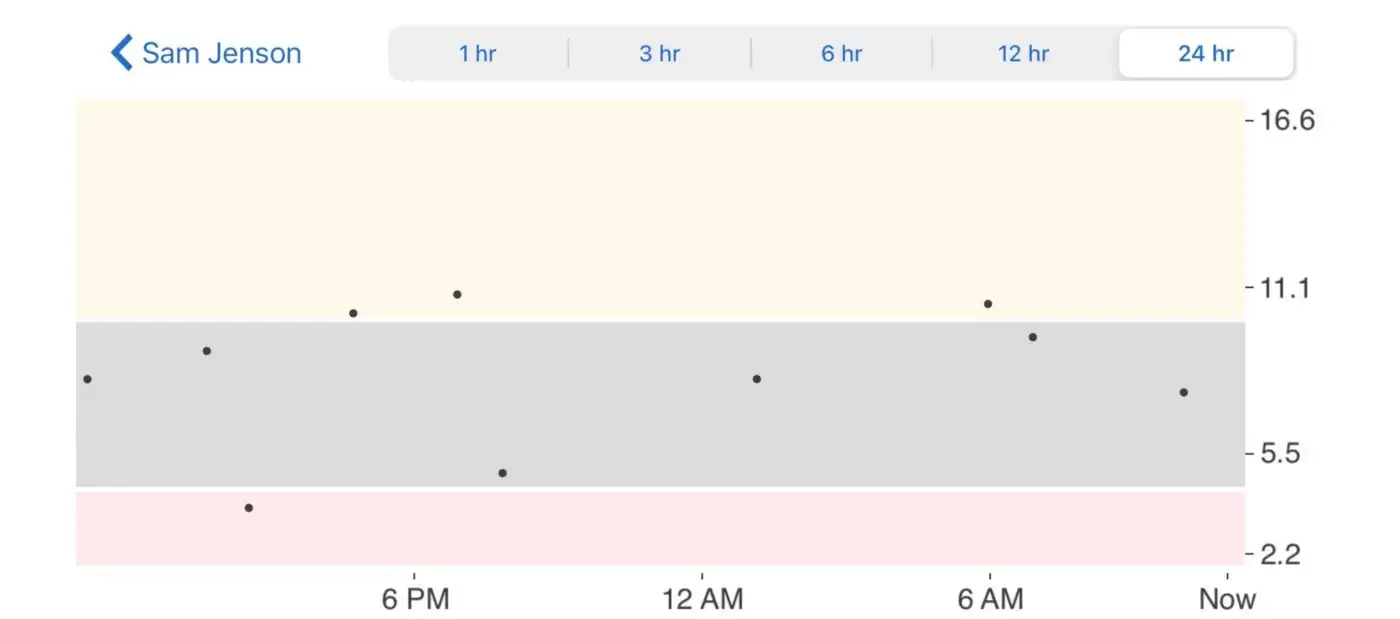

“Quantity has a quality all its own”; the amount of data that a CGM produces isn’t just more of the same data you get from a manual blood glucose meter. Let’s look at the difference:

The additional data shows you exactly what is happening and allows you to learn and adapt with that knowledge.

It is also MUCH safer! Do you see that 2.2 mmol/L reading happening at midnight? Undetected lows are what we are most scared of. Even if I woke up every night and tested at 10pm and 2am, I would have still missed it by 2 hours!

A CGM fundamentally changed the way we managed diabetes by:

- seeing BGL at any time. Among other things, this lets us quickly answer the question “is this tantrum because he is low?” without needing to hold down and stab a screaming toddler.

- showing a direction that BGL is going. 10mmol/L and going up means I might need to correct, 10mmol/L and going down means everything is going to plan.

- notifying us if BGL is too high or low. I have multiple alarms set to wake me if I need to do something. The last thing I do before going to bed each night is make sure the alarms are set correctly.

- showing Time-In-Range (TIR), the % of the day spent between

3.9-10mmol/L. This is the main metric we try to improve; a good day is 70%, our best day is 96%. - showing patterns of how insulin and food affect BGL. CGMs show you directly what food and insulin does to you BGL, so you can better adapt.

Long term T1D

Having a CGM has made us less worried about short term T1D problems. Now we have more time to worry about the long term complications like going blind (retinopathy), losing limbs (amputation) and organ failure (heart and kidney failure). This is a different kind of worry.

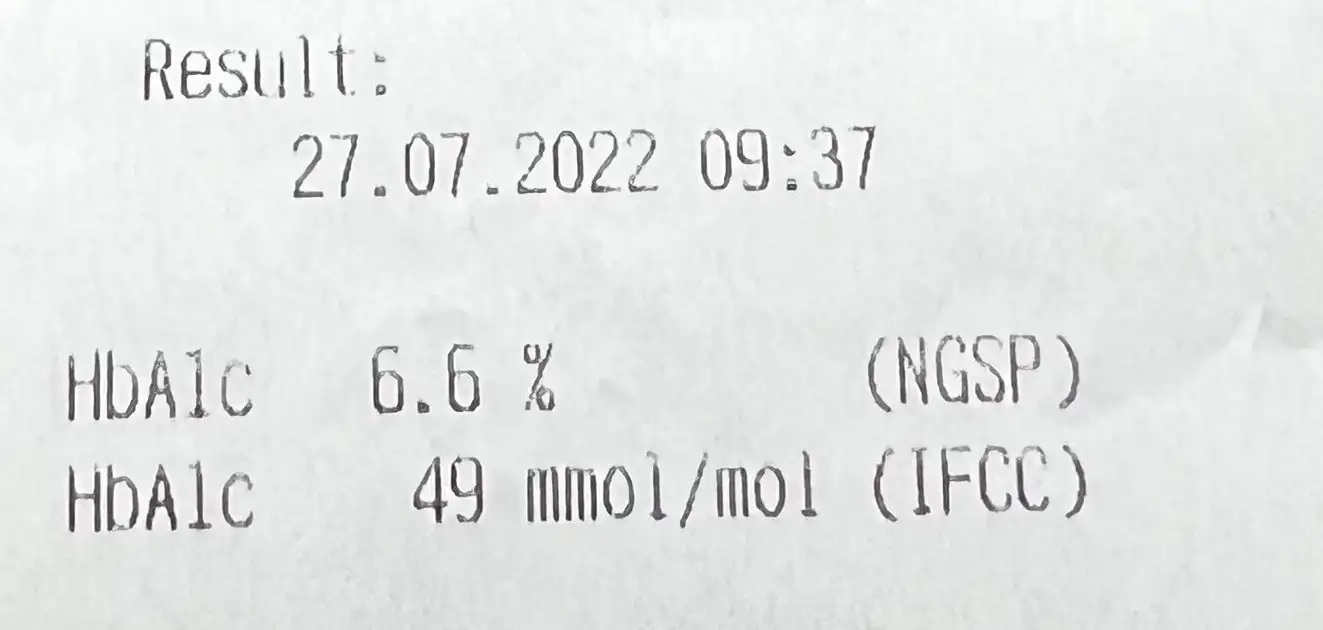

A lot of research has shown HbA1c is the best predictor of long term effects of T1D.

What is HbA1c? Glucose in the bloodstream will sometimes randomly link (glycate) with a red blood cell’s haemoglobin (Hb) creating “Glycated haemoglobin” or HbA1c. The more glucose there is in the bloodstream the more likely this linking will happen. A red blood cell is in circulation for about 120 days, so the amount of HbA1c in the bloodstream can be used to approximate average blood glucose level over that time. More on HbA1c here.

In the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) that involved 1,441 type 1 diabetics for 6 years (1983–1989), a high HbA1c was the best predictor for the long term effects of T1D. For example, every 1% drop in HbA1c gives a 30% drop chance of developing retinopathy [cite].

Sam’s HbA1c when on MDI was good:

I am really proud of 6.6%. It is well under the 7% that the 2020 guidelines from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends for children.

However, according to one study only about 10% of kids from 2–5 are under that 7% guideline. Why are so few kids in the recommended range?Socioeconomic status, parental education [cite] and use of a CGM [cite] are all related to better HbA1c results.

Sam’s good HbA1c results are because my wife and I can take care of Sam fulltime and we can afford a CGM. I want to make it very clear that HbA1c results, like many things, are a measure of privilege and not a lack of willpower or moral failing. This disease hurts people more if they are already struggling, and that is just one more shitty thing about T1D.

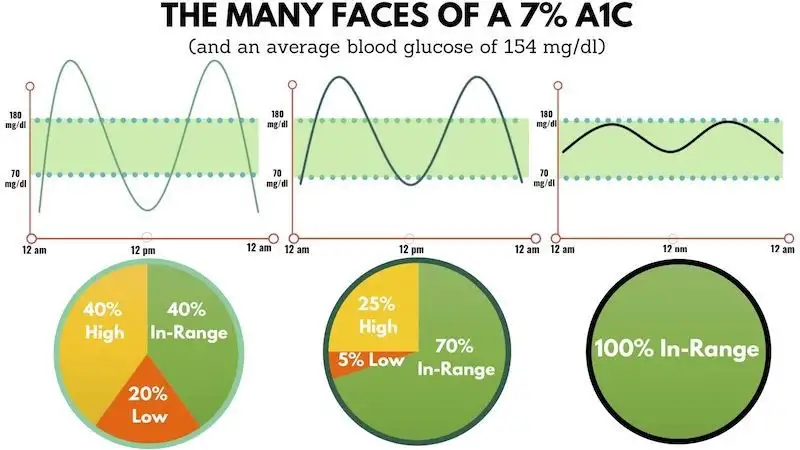

HbA1c is useful, though it is not the full story. For example, here are three people with an HbA1c of 7%:

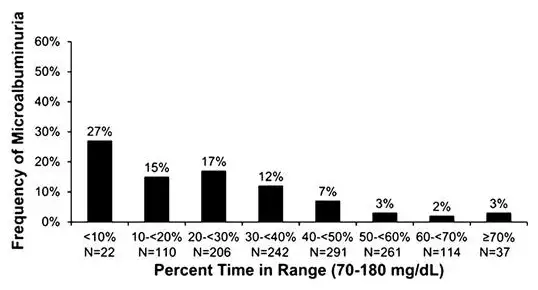

As you can see, a person can maintain an HbA1c of 7% but still have large BGL swings (Glucose Variability GV) and low time-in-range (TIR) . Both bad GV and TIR have been linked to health complications [cite, cite]. For example, here is the relationship between TIR and microalbuminuria (a sign of kidney disease):

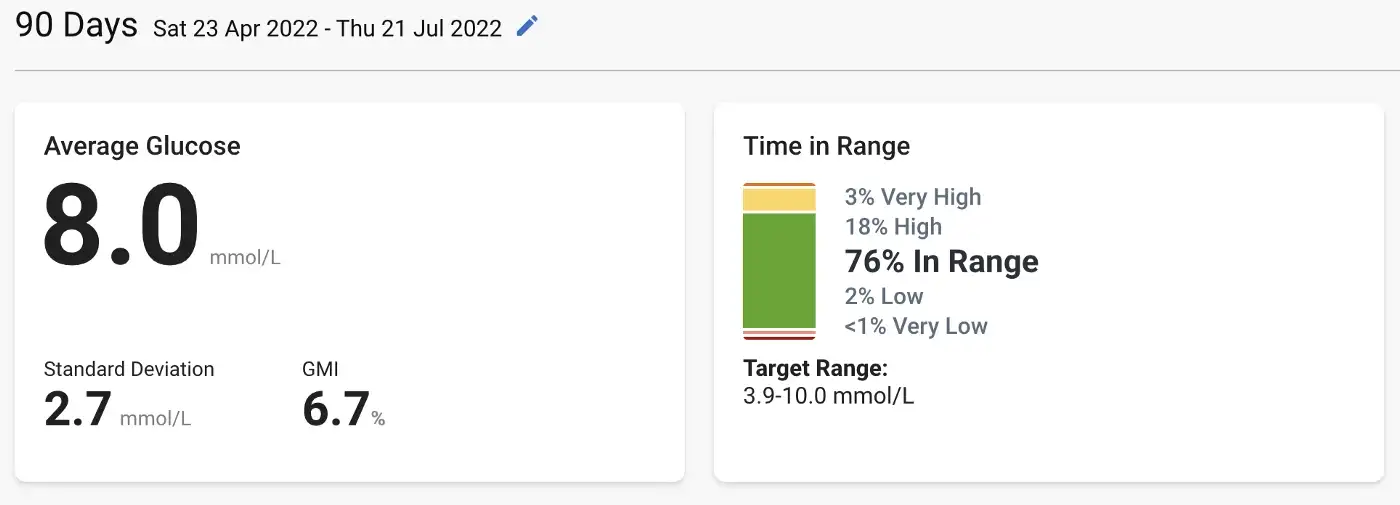

There is no medical test that can approximate GV or TIR, so GV and TIR have to be calculated from the CGM data. Here is Sam’s TIR and GV:

This shows his:

- Glucose Variability (GV), measured as standard deviation, is 2.7 mmol/L.

- GMI, which is an approximation of the HbA1c, was 6.7%. So pretty close to the actual 6.6% result.

- his Time-In-Range (TIR) is 76%, with 21% above range and 3% below. This is within a recommended range [cite] of 70% TIR, above target less than 25% and 4% below.

This is all more good news for Sam.

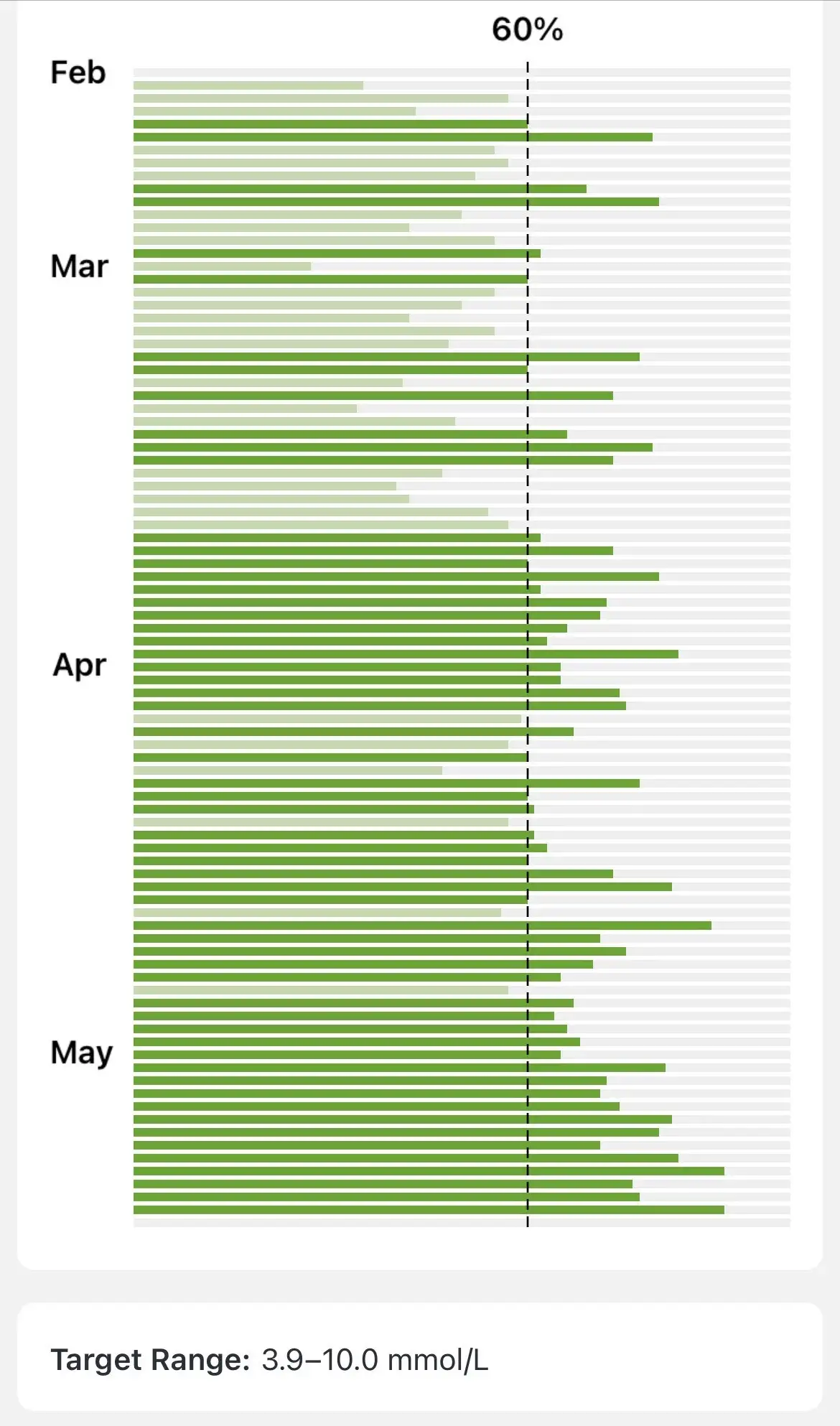

Although Sam has a good TIR now, we definitely didn’t start there. A core benefit of a CGM is that it gives you the power to improve. You can actually see us getting better at managing T1D by looking at Sam’s TIR over many months:

The biggest change we made to improve his TIR was “the loop” (which I discussed in my preivous post).

The CGM Loop (aka Pancreas Job Description)

The CGM loop we use has been described as Sugar Surfing or bump and nudge. The idea is to observe the BGL patterns and adapt your strategies to get blood sugars to where you want them.

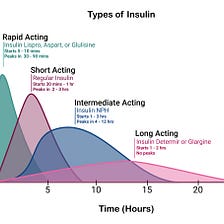

Firstly, using the CGM and experimenting with food and insulin, we were able to approximated his ratios as being:

- Carbohydrate Ratio (CR) is 1:20, e.g. 1 unit of insulin for 20g of carbs

- Insulin Sensitivity Factor (ISF) is 1:10, e.g. 1 unit of insulin will drop Sam’s BGL by 10 mmol/L

- ISF:CR is 10:20 or 1:2, e.g. 2g of carbs will raise Sam’s BGL by 1 mmol/L

Note: These are only approximations because his insulin sensitivity changes a lot during the day; typically for dinner we give 10–20% less insulin.

Applying those ratios is not as easy though as our insulin pens (used to inject insulin) were not made for kids as small as Sam. They can only deliver at 0.5u intervals, so we can:

- correct for 5, 10 or 15 mmol/L with 0.5u, 1u, 1.5u of insulin

- give meal insulin for 10, 20 or 30g of carbs with 0.5u, 1u, 1.5u

Since we can give finer grained carbs, e.g. a 2g gummy, we tend to round up the insulin doses and then bring him up later with small snacks. This makes our Meal Time Loop look like:

- Look at BGL. Add 0.5u to

correction insulinfor every 5 mmol/L we want to bring him down. - Calculate the meal insulin by doing a quick carb count (and rounding up to the nearest 10g) add 0.5u of insulin to

meal insulinfor every 10g of carbs. - Inject the

meal insulin + correction insulinunits. However, if the meal dose is more than 1.5u we will split it into two injections and give the second one as he starts to eat. Anything more than 1.5u drops his BGL too fast. - Wait until he is about 6 mmol/L OR for 20 minutes OR until he starts to drop quickly OR he starts demanding food before giving him the food. This is a gut call based on the situation.

- Eat the food. If he doesn’t eat everything, keep an extra close eye BGL.

- Repeat for every meal.

There is a lot of inaccuracy in the above loop, we are doing a lot of rounding and guessing. This does mean that we have to always keep an eye on Sam’s BGL with the Monitoring Loop:

- Glance at his CGM data and look at BGL reading, direction and the rate of change.

- Predict his future BGL. Try and guess what Sam’s BGL will be in about 5, 10, 30, 60 minutes out. You have to consider the CGM lag (CGMs are 10 mins behind), rate of change, when he last had some carbs or insulin, activity level, temperature, time of day, and anything else that might affect his BGL. This is a shot in the dark. You do seem to get better at it though, since you are practising every 5 minutes.

- Calculate dose. Now that we have a guess of what he will be in the future we can change that by either giving some food or some insulin. Sam’s BGL will go up 1 mmol/L with 2gs of sugar or drop by 5 mmol/L with 0.5u of insulin.

- Do we dose? We will always give carbs if he risks going very low. Otherwise, we have to decide how confident we are in the above guesses to give him insulin or carbs. There is always the option to wait another 5 minutes to see if your guess was right.

- Dose. It is easier to give Sam sugar than insulin.

- Wait 5 minutes for the next reading. Go to the step 1

We run these loops all day, every day. This is what the daytime of being a diabetic is like, why replacing a pancreas is a full time job.

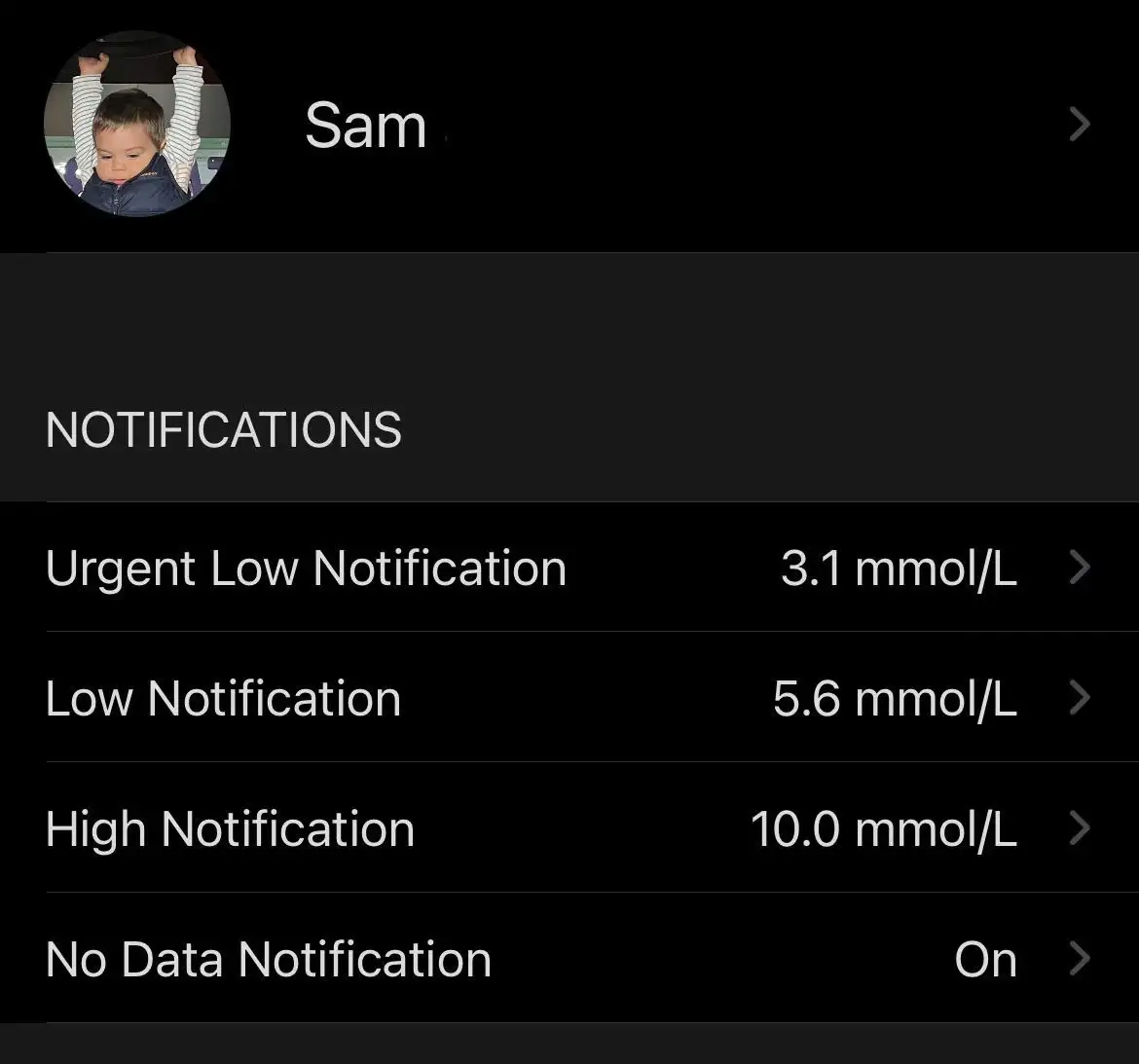

Also part of the job, every night you are oncall. At night, we rely on alarms to wake us if we need to do something. My alarms wake me when:

- High alarms (over 10mmol/L for an hour)

- Low alarm alert (under 5.6mmol/L)

- Urgent Low Alarm (under 3.1mmol/L)

We use the Dexcom Follow app for alarms:

If one of these alarms goes off, we first wake up then we run through the same steps as the monitoring loop. The only differences are:

- Any treatment might wake Sam up, so we will more likely wait and see. FYI: giving him sugar is more likely to wake him than insulin; it seems Sam can sleep through stabbing but not chewing.

- If it isn’t urgent, wait. If you can wait, wait. For example, if I woke up to the low alarm but his BGL looks flat, I will drop the alarm to be at 5.0mmol/L and go back to sleep.

The Meal Loop, the Monitoring Loop and the Overnight Oncall are the major aspects of being a full time pancreas. The more irregular activities include maintaining a stock of supplies, hiding sugary treats everywhere, replacing needles and CGMs and the doctor’s visits.

Once all that is done, you might have time to do other things, like a full time job that pays you money.

Tips and tricks

This is just a bunch of stuff that we wish we would have known earlier.

Meal Loop:

- Splitting up meal insulin into two shots (split bolusing) was one of our biggest improvements. If we gave him 2u for a meal he would drop too fast and it would make the timing very stressful. By splitting the doses we have managed a much stabler rise and drop of blood sugars and allowed us some breathing room if the toddler decides that today he hates pasta (for whatever reason they decide these things)

- We say “prickle” before any finger prick or injection to calm him down. Sam doesn’t actually mind injections so much, he just hates being held still. Saying “prickle” lets him know that once we are done he can go run around again.

- Find ISF and CR ratios in the morning. The only time during the day a toddler has not eaten something is right after they wake up. The rest of the day is full of snacks and running around. The morning is the best time to dial in those ratios.

- Keto sometimes. If Sam is high but he is hungry or deserves a reward we usually turn to keto bread, keto gummies, keto jelly, or lo carb kombucha (juice). Sam is not on a low carb diet, but keto food has allowed us to feed him without feeling guilty.

Monitoring Loop:

- Identify basal insulin patterns. We noticed 2–3 hours after Protaphane he would go super low. We switched to Lantus which would drop much slower after 4–5 hours. This increased Sam’s TIR a ton.

- Keep records. Having a good record of when insulin or carbs are given helps a ton in timing and identifying patterns.

- iPhone display set up with night mode and “guided access” will not let it sleep so that I can glance at BGL anytime during the night. Note: guided access will stop alarms from working, so I use an old iphone as a display.

Overnight Oncall:

- Use diluted insulin. If Sam is 12mmol/L at bedtime, a pen would deliver too much insulin. We got diluted insulin which we can give accurately from a needle and we use only for nighttime corrections.

- Rules of thumb for quick action. At 2am doing calculations is hard. I recommend simplifying the maths to easy to follow rules, like if the low alarm goes off, give 4g of carbs, set an alarm for 30 mins, then go back to sleep.

My wife and I are both working full time as Sam’s pancreas to give him the best chance at a long and healthy life. It takes a lot of time and effort but Sam is doing great. Without a CGM we would be back in the fearful, unsustainable dark days and Sam would undoubtedly be doing worse. Every person diagnosed with type 1 diabetes should walk out of the hospital with a free CGM. I hope this will be the case soon.

Next Steps

I started writing this post at the end of Sam being on MDI, so it is a little out of date. Sam is now on the Dana-I pump looping with CamAPS, I wrote about our pump selection here.

I have already started to write about our experiences with CamAPS. For the impatient, CamAPS + Dana-i:

- is good.

- is not a silver bullet.

- requires xDrip to get Dexcom follow alarms to work.

- doesn’t show the information I want, so I made a custom app I plan on releasing.

- we get better results with less guessing, decisions and bad nights.