I Spent a Week With Gemini

Pro 1.5—It’s Fantastic

When it comes to context windows, size matters

Sponsored By: Destiny

Own game-changing companies

Venture capital investing has long been limited to a select few—until now.

With the Destiny Tech100 (DXYZ) , you'll be able to invest in top private companies like OpenAI and SpaceX from the convenience of your brokerage account.

Claim your free share before it lists on the NYSE. Sponsored by Destiny.

I got access to Gemini Pro 1.5 this week, a new private beta LLM from Google that is significantly better than previous models the company has released. (This is not the same as the publicly available version of Gemini that made headlines for refusing to create pictures of white people. That will be forgotten in a week; this will be relevant for months and years to come.)

Gemini 1.5 Pro read an entire novel and told me in detail about a scene hidden in the middle of it. It read a whole codebase and suggested a place to insert a new feature—with sample code. It even read through all of my highlights on reading app Readwise and selected one for an essay I’m writing.

Somehow, Google figured out how to build an AI model that can comfortably accept up to 1 million tokens with each prompt. For context, you could fit all of Eliezer Yudkowsky’s 1,967-page opus Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality into every message you send to Gemini. (Why would you want to do this, you ask? For science, of course.)

Gemini Pro 1.5 is a serious achievement for two reasons:

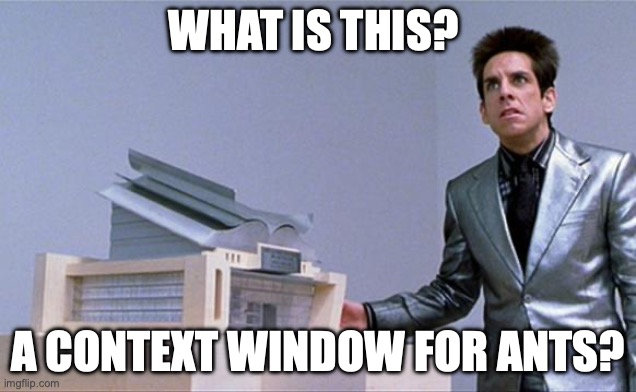

1) Gemini Pro 1.5’s context window is far bigger than the next closest models. While Gemini Pro 1.5 is comfortably consuming entire works of rationalist doomer fanfiction, GPT-4 Turbo can only accept 128,000 tokens. This is about enough to accept Peter Singer’s comparatively slim 354-page volume Animal Liberation, one of the founding texts of the effective altruism movement.

Last week GPT-4’s context window seemed big; this week—after using Gemini Pro 1.5—it seems like an amount that would curl Derek Zoolander’s hair:

2) Gemini Pro 1.5 can use the whole context window. In my testing, Gemini Pro 1.5 handled huge prompts wonderfully. It’s a big leap forward from current models, whose performance degrades significantly as prompts get bigger. Even though their context windows are smaller, they don’t perform well as prompts approach their size limits. They tend to forget what you said at the beginning of the prompt or miss key information located in the middle. This doesn’t happen with Gemini.These context window improvements are so important because they make the model smarter and easier to work with out of the box. It might be possible to get the same performance from GPT-4, but you’d have to write a lot of extra code in order to do so. I’ll explain why in a moment, but for now you should know: Gemini means you don’t need any of that infrastructure. It just works.

Let’s walk through an example, and then talk about the new use cases that Gemini Pro 1.5 enables.

VC investing has traditionally been reserved to a privileged few. But now Destiny Tech100 (DXYZ) is changing that. You can own a piece of groundbreaking private companies such as OpenAI and SpaceX, all from the convenience of your brokerage account. Claim your free share before it hits the NYSE. Sponsored by Destiny.

Why size matters (when it comes to a context window)

I’ve been reading Chaim Potok’s 1967 classic novel, The Chosen. It features a classic enemies-to-lovers storyline about two Brooklyn Jews who find friendship and personal growth in the midst of a horrible softball accident. (As a Jew, let me say that yes, “horrible softball accident” is the most Jewish inciting incident in a book since Moses parted the Red Sea.)

In the book, Reuven Malter and his Orthodox yeshiva softball team are playing against a Hasidic team led by Danny Saunders, the son of the rebbe. In a pivotal early scene, Danny is at bat and full of rage. He hits a line drive toward Reuven, who catches the ball with his face. It smashes his glasses, spraying shards of glass into his eye and nearly blinding him. Despite his injury, Reuven catches the ball. The first thing his teammates care about is not his eye or the traumatic head injury he just suffered—it’s that he made the catch.

If you’re a writer like me and you’re typing an anecdote like the one I just wrote, you might want to put into your article the quote from one of Reuven’s teammates right after he caught the ball to make it come alive.

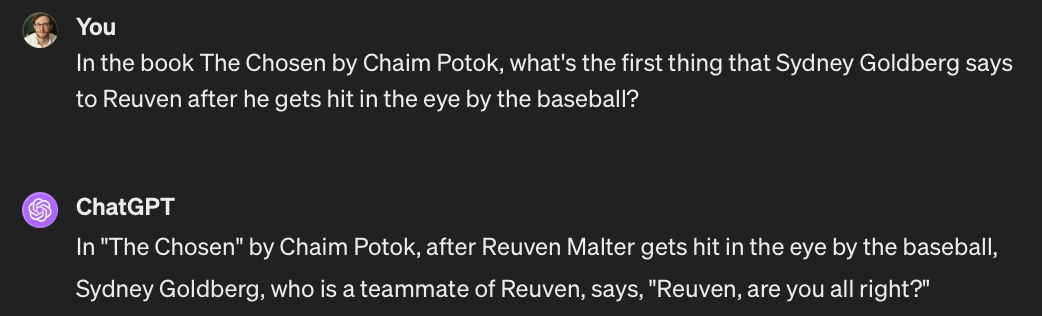

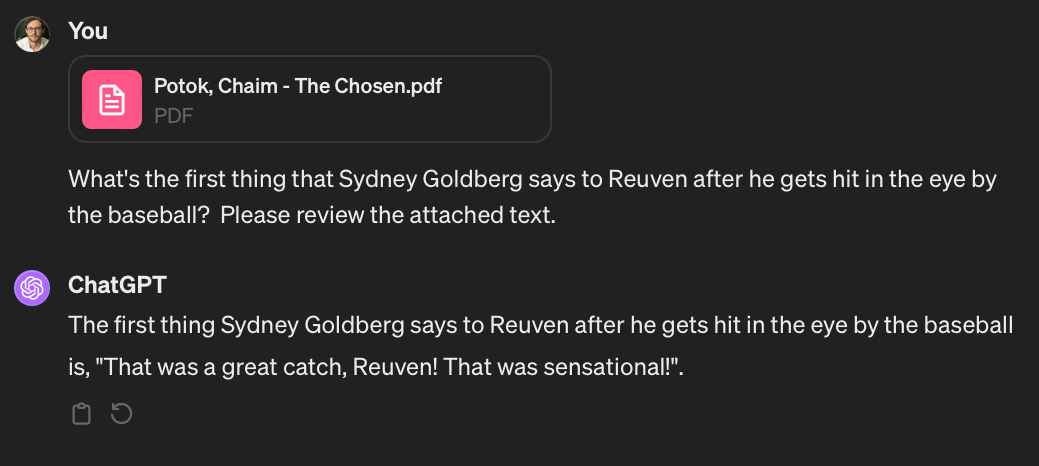

If you go to ChatGPT for help, it’s not going to do a good job initially:

This is wrong. Because, as I said, Sydney Goldberg did not care about Reuven’s injury—he cared about the game! But all is not lost. If you give ChatGPT a plain text version of The Chosen and ask the same question, it’ll return a great answer:This is correct! (It also confirms for us that Sydney Goldberg has his priorities straight.) So what happened?ChatGPT behaved as if I’d given it an open-book test. We can improve ChatGPT’s responses by, when asking it a question, giving it a little notecard with some extra information that it might use to answer it.

In this case we gave it an entire book to read through. But you’ll notice a problem: The entire book can’t fit into ChatGPT’s context window. So how does it work?

In order to answer my question, there’s a lot of code in ChatGPT that performs retrieval: It divides The Chosen up into small chunks through which it searches to find ones that seem relevant to the query. The retrieval code passes the original question, “What’s the first thing that Sydney Goldberg says to Reuven after he gets hit in the eye by the baseball?” and the most relevant sections of text it can find in the book to GPT-4, which produces an answer. (For a more detailed explanation, read this piece.)

Again, we have to pass GPT-4 chunks of text—not the whole book—because GPT-4 can only fit so much text into its context window. If you’re paying attention, you’ll see the problem: Because the context window is so small, the performance of our model for answering certain kinds of queries is bottle-necked by how good we are at searching for relevant pieces of information to give to the model. (I wrote about this phenomenon about a year ago in this piece.)

If our search functionality doesn’t turn up relevant text chunks, well, GPT-4’s answer won’t be good. It doesn’t matter how smart GPT-4 is—it’s only as good as the chunks we turn up.

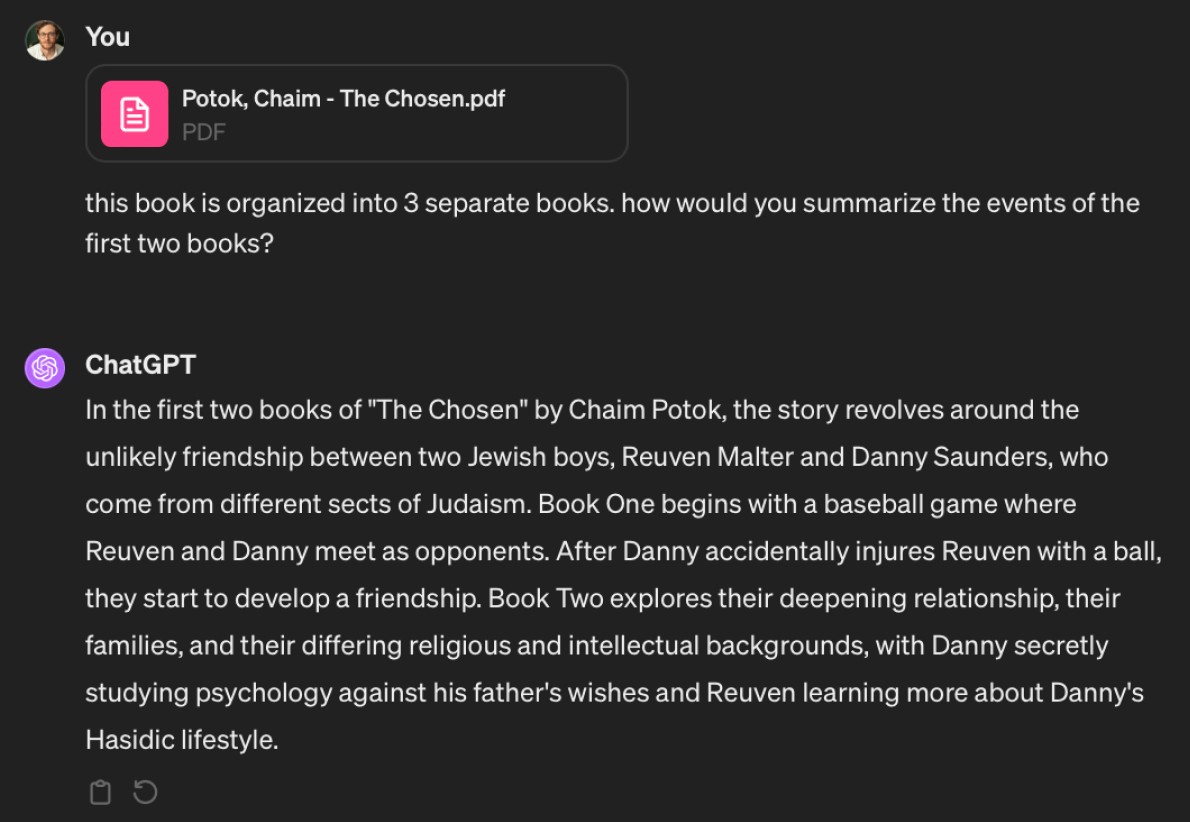

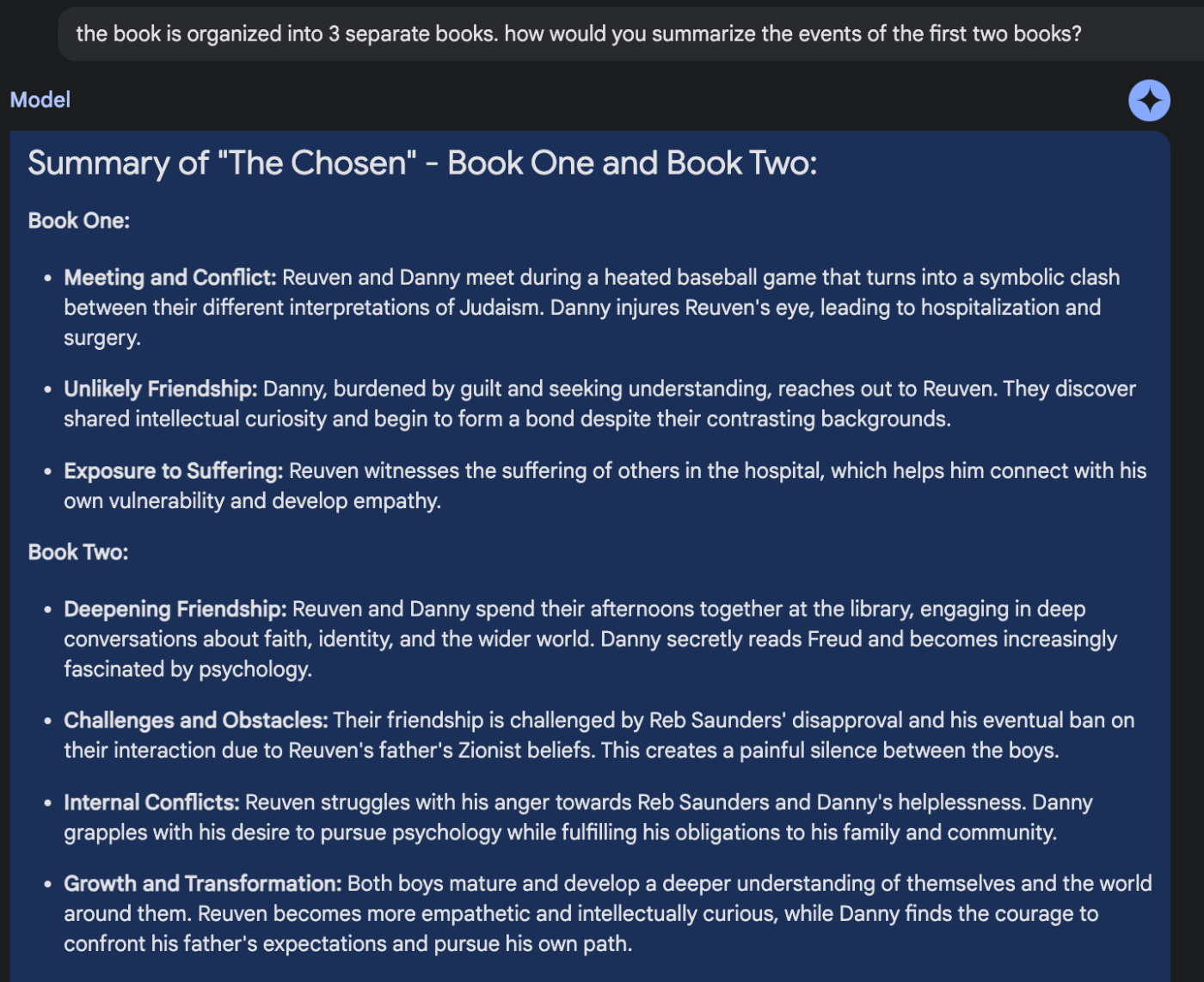

Let’s say we’re picking up The Chosen after a few weeks. We’ve read the first two sections, and before we begin the third we want to get a summary of what’s already happened in the book. We upload it to ChatGPT and ask it to summarize:

ChatGPT gives us a vague answer that’s correct, but it’s not very detailed because it can’t fit enough of the book into its context window to output a great one.Let’s see what happens when we don’t have to divide the book up into chunks. Instead, we use Gemini, which can read through the entire book at once:

You’ll notice that Gemini’s answer is significantly more detailed and provides key plot points from the book that ChatGPT can’t give. (Technically, we could probably get a similar summary out of GPT-4 if we devised a clever system for chunking and summarizing it, but it would take a lot of work, and Gemini makes that work unnecessary.)Gemini’s use cases aren’t limited to reading novels of self-discovery through softball accidents. There are hundreds of others that it unlocks that were previously difficult to do with ChatGPT, or with a custom solution.

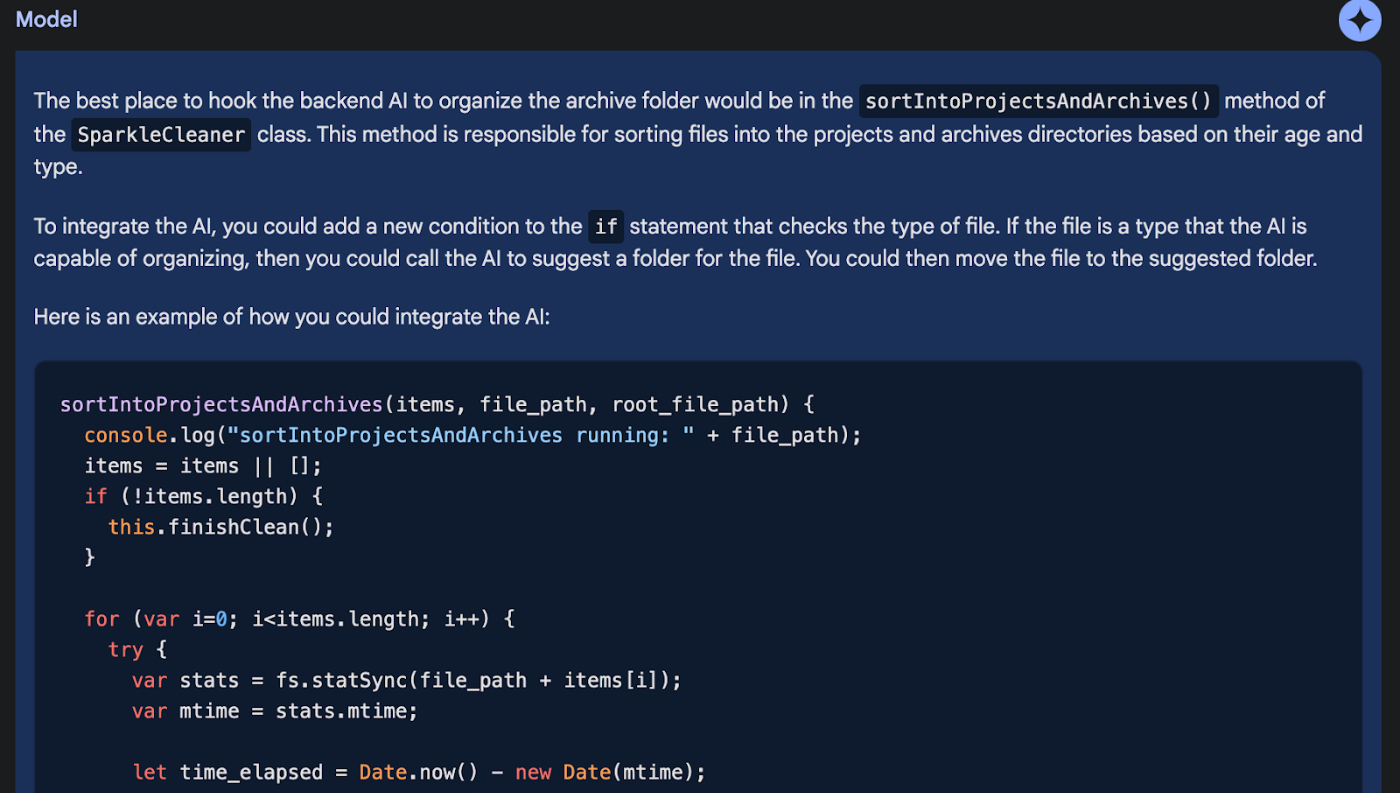

For example, at Every, we’re incubating a software product that can help you organize your files with AI. I wrote the original code for the file organizer, and our lead engineer, Avishek, wrote a GPT-4 integration. He wanted to know where to hook the GPT-4 integration into the existing codebase. So we uploaded it to Gemini and asked:

It found the right place in the code and wrote the code Avishek needed in order to complete the integration. This is something just short of magic, dramatically accelerating developer productivity, especially on larger projects.It doesn’t stop there, either. I’ve been writing for a long time about how transformer models might become copilots for the mind—and end our need to organize our notes forever. Gemini Pro 1.5 is a step in that direction. For example, recently I was writing a piece about an effect I’ve noticed that I’m calling “I can do it myself” syndrome, where people tend to not use ChatGPT and similar tools because they feel like they can get the same task done more quickly, at better quality, if they do it themselves. It’s like inexperienced managers who micromanage their reports to the point of doing most of the work themselves, guaranteeing it’s done the way they want it to, but sacrificing a lot of leverage in the process.

I wanted an anecdote to open the essay with, so I asked Gemini to find one in my reading highlights. It came up with something perfect:

I could not have found a better anecdote, and it’s not a generic one—it’s from my own reading history and taste.Again, all of this comes back to the context window. This kind of performance is only possible because with Gemini we don’t need to search for or sort relevant pieces of information before we hand it to the model. We just feed it everything we have and let the model do the rest.

It’s much easier to work with large context windows, and they can deliver far more consistent and powerful results without extra retrieval code. The question is: What’s next?

The future of large context models

About a year ago I wrote:

“People have been saying that data is the new oil for a long time. But I do think, in this case, if you’ve spent a lot of time collecting and curating your own personal set of notes, articles, books, and highlights it’ll be the equivalent of having a topped-off oil drum in your bedroom during an OPEC crisis.”

Gemini is the perfect example of why this is true. With its large context window, all of the personal data you’ve been collecting is at the tip of your fingers ready to be deployed at the right place and the right time, in whatever task you need it for. The more personal data you have—even if it’s disorganized—the better.

There are a few important caveats to note, though:

First, this is a private beta that I can use for free. These models often perform differently (read: worse) when they are released publicly, and we don’t know how Gemini will perform when it’s tasked with operating at Google scale. There’s also no telling how much pumping 1 million tokens is going to cost into Gemini when it’s live. Over time the cost of using it will likely significantly decrease, but it will take a while.

Second, Gemini is pretty slow. Many requests took a minute or more to return, so it’s not a drop-in replacement for every LLM use case. It’s for the heavy lifting that you can’t get done with ChatGPT, which you probably don’t need to do on a regular basis. I would expect speed to increase significantly over time as well, but it’s still not there yet.

OpenAI has some catching up to do, and I’ll be watching to see how they respond. But the other players on my mind—companies like Langchain, LlamaIndex (where I’m an investor), Pinecone, and Weaviate—are to some degree betting on retrieval being an important component of LLM usage. They either provide the library that does the chunking and searching for information to pass to the LLM, or the datastore that keeps the information searchable and safe. As I mentioned earlier, retrieval is less relevant when you have a large context window, because you can input all of your information into each request.

You might think those companies are in trouble. Gemini’s huge context window does make some of what they’re building less important for basic queries. But I think retrieval will still be important long-term.

If there’s one thing we know about humanity, it’s that our ambition scales with the tools we have available to satisfy it. If 1 million token context models become the norm, we’ll learn to fill them. Every chat prompt will include all of our emails, and all of our journal entries, and maybe a book or two for good measure. Retrieval will still be used to figure out which 1 million tokens are the most relevant, rather than what it’s used for now: to find which 1,000 tokens are the most relevant.

It’s an exciting time. Expect more experiments from me in the weeks to come!

Dan Shipper is the co-founder and CEO of Every, where he writes the Chain of Thought column and hosts the podcast How Do You Use ChatGPT? You can follow him on X at @danshipper and on LinkedIn, and Every on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

Thanks to our sponsor: Destiny

If you’re fond of unicorns, AI, and space—get a Destiny Tech100 share. You'll be able to own a piece of OpenAI, SpaceX, Discord, Stripe, and others. Claim your free share before the NYSE listing. Sponsored by Destiny.

Comments