Sometimes, for example when I watch the Lord of the Rings movies (extended edition) for the nth time, I get annoyed by how simplistic J.R.R. Tolkien’s fictional Middle-earth is.

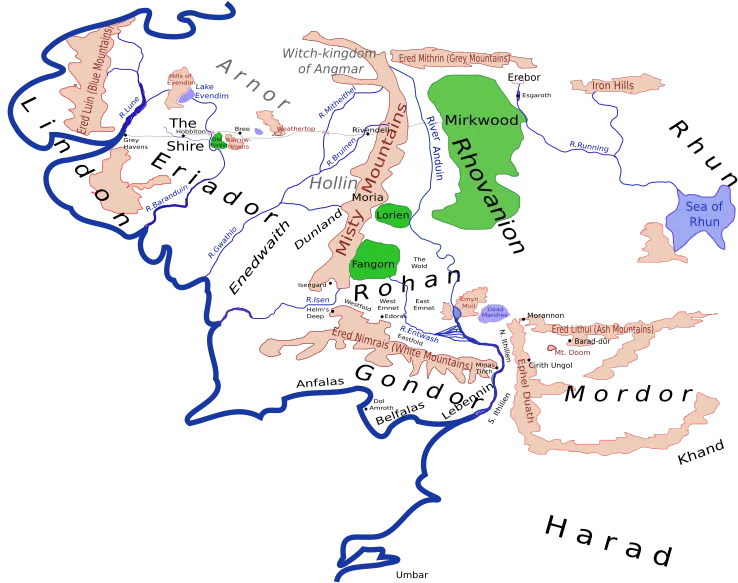

First let’s consider some maps. Almost everything we know about Middle-earth (the world) concerns this sort of subcontinental area, which I’m also going to call Middle-earth:

This area is supposed to roughly correspond, in size, to Europe:

So, pretty big. Yet, at the time the most well-known stories (LotR and The Hobbit) are set, there are what, six or seven identifiable countries?1 Most of the land is terra nullius, land that belongs to nobody, which in the real world occurs basically only in Antarctica and those two weird triangles of desert between Egypt and Sudan. A lot of Middle-earth’s population seems to be living in random towns scattered throughout that terra nullius, with barely any roads or any sort of economic network between them. Long-distance communication apparently consists entirely of people riding horses (I can understand why Saruman gave in and started using his evil Palantir stone to overcome this limitation). The small town of Bree in the north is canonically said to be, together with a few adjacent villages, the only human settlement in all of Eriador — suggesting a density of population comparable to Greenland. In fact he population of the entire subcontinent — counting humans, hobbits, elves, dwarves and orcs — has been estimated to anywhere between 2 and 7 million, i.e. a small modern country, or a middle-sized medieval one (Europe in the year 1000 had about 55-60 million people, and its largest countries probably 5-10 million). Necessarily, this relatively small population means little of everything: little culture, little commerce, little diplomacy and politics, little complexity of any kind.

Middle-earth is similar to Europe not only in size, but also in culture and technology. Or at least, those are similar to medieval Europe, which is quite obviously a big part of the inspiration for Tolkien’s worldbuilding.

Meanwhile, actual medieval Europe:

And sure, there were times when Europe had far fewer countries, people, and complexity, like at the height of the “Dark Ages,” making the comparison with Middle-earth less lopsided:

But this comes with an important point: in real-life Europe (and the world), things change a lot. It’s a constantly self-evolving system, not a designed one, and as a result the world was vastly different between 600 and 1444 AD. Whereas Middle-earth is fairly static: over about 12,000 years, civilization seems to have been stuck at the same level of development.

(Maybe because the one guy who tries to industrialize, in addition to being the only one to use telecommunications, is swiftly defeated by an army of slow-moving talking trees.)

And of course, the planet of Middle-earth is bigger than just the subcontinental region we’re focusing on — but then real Earth is also far bigger than Europe, and unlike in Tolkien’s world, the regions outside Europe are also complex and have been interacting with Europe in intricate ways forever. In LotR, places like Harad and Rhun exist, but they seem to do little other than send armies to fight for Mordor.

So: Tolkien’s mythical Middle-earth is a relatively unchanging world over thousands of years, consisting of half a dozen countries and perhaps a hundred settlements known by name, with the theoretical population of a medium-sized medieval country. That’s not complex. That’s not vast, not infinite. It’s a simple world, a mere backdrop to stage a cool story.

At this point Tolkien fans are rushing to the comment section to tell me how wrong I am. How can I describe Tolkien’s legendarium as simple?? It’s the most awe-inspiring work of worldbuilding ever done! He invented entire languages! He came up with a deep, coherent mythology! He wrote all this backstory in The Silmarillion or whatever, it’s not just Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit (or, god forbid, the movies)! And also, after his death, his son continued his work, such that Middle-earth is the accomplishment of decades and decades of human imagination!

To which I respond: Yup. I agree, it’s the most incredible piece of fictional worldbuilding ever made. And yet it has the complexity of… I don’t know, Denmark, maybe. Or half of Denmark. A fraction of a small country.

I love Denmark, but I would be sad if there was only half a Denmark and nothing else.

Of course, the point of worldbuilding isn’t necessarily to replicate the complexity of the real-world. Instead it’s about telling cool stories, and exploring cool ideas, and escaping to cool imaginary places. Fictional worlds are cool! But I don’t think I’m wrong to claim that fictional worlds are cooler when the more intricate they are. We yearn for believable world that at least feel realistic even if they aren’t.

And if it takes a lifetime to make something that gets less than 1% of the way there, that’s quite the indictment against the very concept of worldbuilding.

In a way that’s not s super surprising observation: obviously a world created through the work of a single author (or a few) will not be as complex as one created through the interaction of 8 billions of humans, plus billions of past humans, plus natural phenomena. Naïvely we might even expect a fictional world to be at least 8 billion times less complex than the real world, whatever that means. Maybe Tolkien got 0.000000000125% of the way there, and all other authors who tried got 0.0000000001% or less.2

It’s still an interesting observation because it ties into the wider philosophical theme of evolution vs. design. Design is great: it’s much smarter and faster than evolution is, it allows us to use our brains to create really cool stuff. But evolution through selection has time on its side, and so far every really complex system known to man — including biological systems like the human body, and cultural ones like human civilization — has been the product of evolution rather than intelligent design.

Maybe we’ll get on the same level as evolution, once we all become superintelligent through cognitive enhancement. In the meantime, whoever tries to build a fictional world is doomed to make a tiny, simple toy version of the real thing.

As a kid I loved inventing fictional worlds. It is only later that I decided it was more interesting to write stories set in our good, old, complicated Earth than to try to reinvent it. Better to explore a small fractal of reality than to construct an imaginary version that will always fall short of the ideal.

But I still love fictional worlds, and I still read and watch and play stories set in them. Lately that has been a lot of science fiction, notably in the genre of the space opera, which tries to simulate complexity by showcasing giant civilizations across many planets and solar systems. It still fails,3 but less noticeably.

If we like fictional worlds but can’t make them complex enough to be believable, the obvious workaround — in fact the only workaround — is to “borrow” the real world’s complexity.

The most transparent way to do this is to make a world map that isn’t the actual Earth, but also kind of is the actual Earth. One of the video games I loved in my youth is the Japanese RPG Golden Sun, whose world map looks like this:

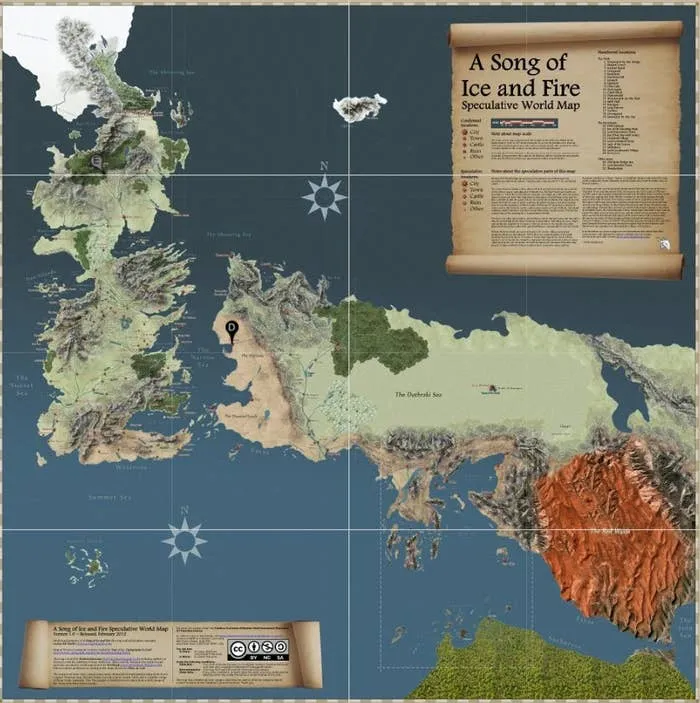

Another great example is A Song of Ice and Fire / Game of Thrones, in which Westeros is clearly some kind of modified Great Britain or medieval Europe, and the other continent a direct inspiration from the eastern Mediterranean and the steppes of Asia. As for the main conflict in the story, a feud between the Lannister and the Stark families, it’s just a remix of the real-life Wars of the Roses between the House of Lancaster and the House of York.

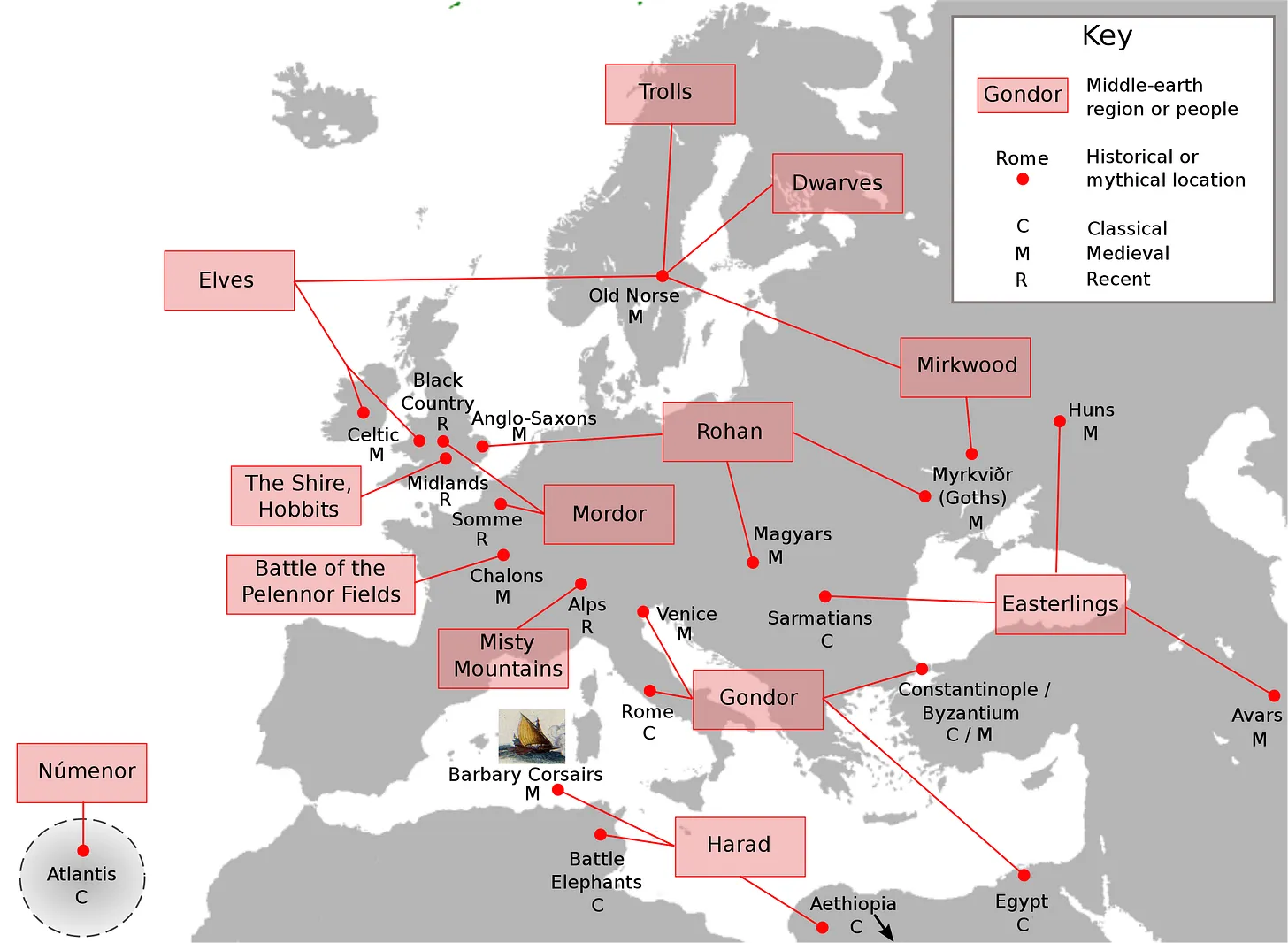

Even Tolkien’s elaborate Middle-earth is, when you dig enough, a remix of the real world. I thank Wikipedia user Ian Alexander for this great map of Tolkien’s influences:

I think part of Tolkien’s genius is that he was better than most fantasy authors at making his world feel novel, even though it is (like all fiction) a remix of real elements. The scope of his influences is vast, from the legends of Atlantis to the olden days of pagan Germanic Europe to industrial England and the horrors of WWI, and over the course of many years of work he managed to turn all of these into something coherent and believable.

But it did take a lot of work, like we saw, and it still relies on the naturally evolved complexity of the real world. Ultimately, all fictional worldbuilding relies on that single, finite resource. All the stories we tell can only ever be remixes of what has happened (and is recorded) in our history.

That’s a lot of stories, and we still have many of those stories to tell. Infinitely many, in fact, since we can remix elements in an arbitrary large number of ways, and also history and evolution haven’t stopped: we’re generating new complexity every minute.

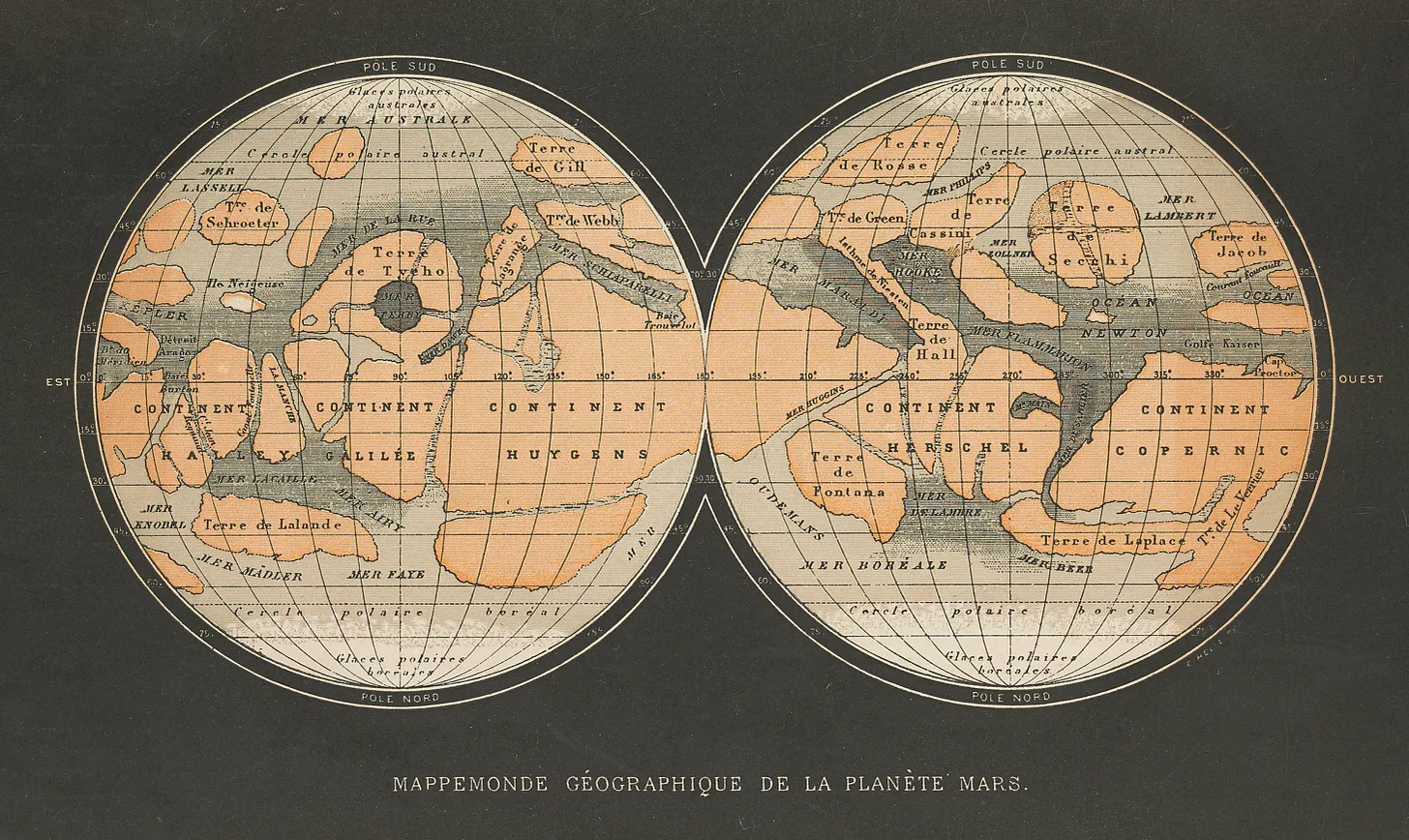

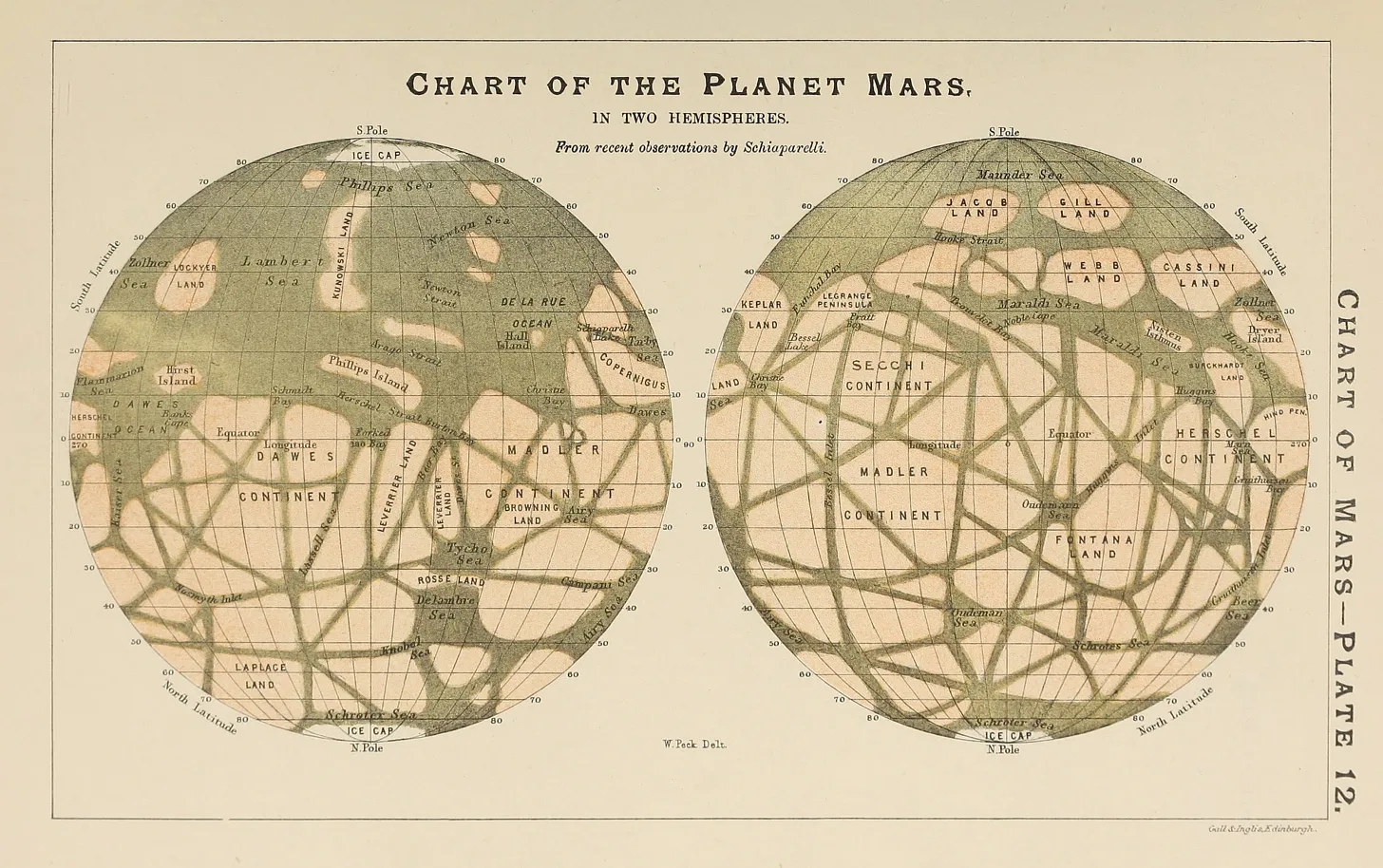

Yet there is a limit to how much complexity there can be on a single planet with a finite number of people. If we wanted to actually see new worlds, we’d need to… do real worldbuilding rather than the fictional version. Colonize planets and let evolution shape them, which it will surely do in all sorts of unforeseen ways. We’d need to have a thousand new civilizations bloom around distant stars, all creating their own fascinating stories in real time.

Maybe that’s actually the most compelling reason to settle Mars and beyond. So that there is, actually, a planet B to draw inspiration from.

Gondor, Rohan and Mordor are the three obvious countries with a visible state structure and meaningful geographic extent. We can add the Elven kingdoms of Mirkwood and Lothlórien, and maybe Dwarven states in the Lonely Mountain and the Iron Hills. The Shire seems like a corner case, but presumably they have some sort of government. Then there are various lands to the south and east, like Harad that are allied with Mordor and surely contain countries, but very almost no detail is given about those.

Both numbers are much less than the share of complexity of Denmark, which has 0.07% of the world population and 0.028% of the world’s land area (not counting Greenland). So half a Denmark might be far more complex than Middle-earth after all.

One specific way in which space operas fail at being complex is by simplifying planets to a single characteristic. Geographically, planets are often treated as a single “biome”: a desert planet, a water planet, a jungle planet. Politically, they’re usually treated as a single state or even a single city. Narratively, there’s often just one location on the entire planet that gets visited by the protagonists over the course of the story.

Imagine some alien space opera in which the heroes visited Earth, and they landed in Denmark, and it looked like this:

And that’s it, it’s all the alien audience will ever see of the Earth. For them, Earth is forever going to be a simplistic “empty meadow planet.” Maybe with a small dose of local culture like Legos or hygge or whatever it is the Danes are into these days.

Subscribe to Atlas of Wonders and Monsters

Hic sunt dracones, among other things

Spoiler Alert: Most readers don’t prefer complex world building. Those that do tell their own stories within those worlds: tabletop gamers.

The more complex the world, the more page space is required to explicate it and the less tight the emotional narrative density is. The lower this density vis a vis exposition, the lower impact the cathartic moments are necessarily due to their sparsity. The Dunbar Number likely has an organization or tribal equivalent that nobody has yet named that’s far less than the 250 individuals humans can normally track without losing their sense of place and social importance into anonymity. I’ll can it the Reed Number and estimate that it’s four to six.

This is why the most complex seeming worlds only give us the illusion of complexity. Herbert gave us a massive seemingly complex universe in Dune, but only a handful of political entities actually duking (sorry!) it out on the page. Martin had five books and really only a dozen different political entities in play in SOIAF--which only began to sell in huge numbers after HBO laid it all bare (literally). I don’t think the mass audience came for the complexity there. Asimov and others, especially in sci-fi, do lay down bigger complexity and unintentionally shrink their audiences when there’s “too much” to track. Family saga novels and series (which you would expect to have high complexity) sell inversely proportional to their actual complexity in my anecdotal observation--not my usual jam, so I’ll admit that’s speculation.

Everyone else gives us four different houses, clans, tribes, species, factions, or whatever. Or the names or numbers of about a dozen states, with only two or three actually being visited or involved in the plot.

I’m sure some aspiring literary academic could make a thesis out of this. And maybe prove me wrong.

You talk about the time it takes to create a new world, but what about the time it takes to explore it?

Stories are always shorts compare to our human life. One human cant write the story of humanity since the beginnings of time. And one would die before finishing to read it.

Especially because we also took time to read about the fictional worlds. Some of us know the maps of video games better than the maps of our own town.

What is it with fiction that make us love it so much? Is it the simplicity? The neutrality? The concentration in short period of high emotions without the boring moment?