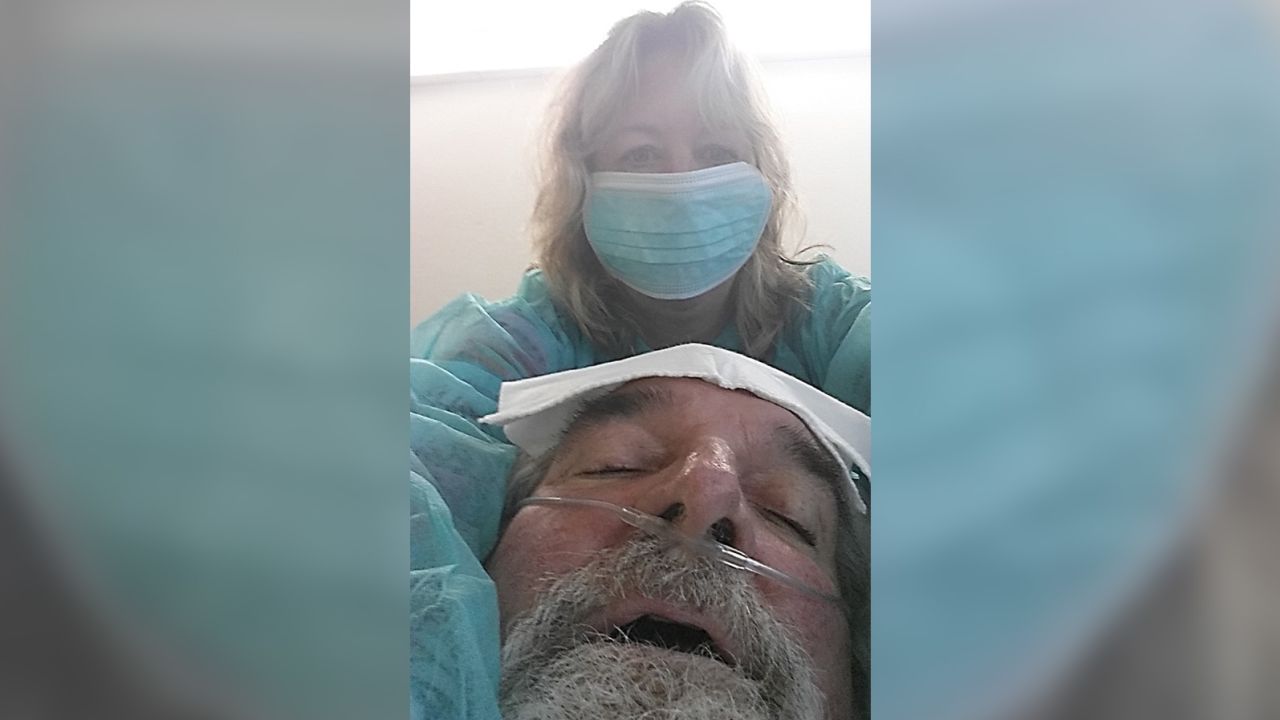

In February 2016, infectious disease epidemiologist Steffanie Strathdee was holding her dying husband’s hand, watching him lose an exhausting fight against a deadly superbug infection.

After months of ups and downs, doctors had just told her that her husband, Tom Patterson, was too racked with bacteria to live.

“And I have this conversation that nobody ever wants to have with their loved one,” Strathdee told an audience recently at Life Itself, a health and wellness event presented in partnership with CNN.

“I said, ‘Honey, we’re running out of time. I need to know if you want to live. I don’t even know if you can hear me, but if you can hear me and you want to live, please squeeze my hand.’

“And I waited and waited,” she continued, voice cracking. “And all of a sudden, he squeezed really hard. And I thought, ‘Oh, great!’ And then I’m thinking, ‘Oh, crap! What am I going to do?’ “

What she accomplished next could easily be called miraculous. First, Strathdee found an obscure treatment that offered a glimmer of hope – fighting superbugs with phages, viruses created by nature to eat bacteria.

Then she convinced phage scientists around the country to hunt and peck through molecular haystacks of sewage, bogs, ponds, the bilge of boats and other prime breeding grounds for bacteria and their viral opponents. The impossible goal: quickly find the few, exquisitely unique phages capable of fighting a specific strain of antibiotic-resistant bacteria literally eating her husband alive.

Next, the US Food and Drug Administration had to greenlight this unproven cocktail of hope, and scientists had to purify the mixture so that it wouldn’t be deadly.

Yet just three weeks later, Strathdee watched doctors intravenously inject the mixture into her husband’s body – and save his life.

Her journey is one of unrelenting perseverance and unbelievable good fortune. It’s a glowing tribute to the immense kindness of strangers. And it’s a story that just might save countless lives from the growing threat of antibiotic-resistant superbugs – maybe even your own.

“It’s estimated that by 2050, 10 million people per year – that’s one person every three seconds – is going to be dying from a superbug infection,” Strathdee told the Life Itself audience.

“We have been caught for the last 2 1/2 years in this terrible situation where viruses have been the bad guy,” she said. “I’m here to tell you that the enemy of my enemy can be my friend. Viruses can be medicine.”

A terrifying vacation

During a Thanksgiving cruise on the Nile in 2015, Patterson was suddenly felled by severe stomach cramps. When a clinic in Egypt failed to help his worsening symptoms, Patterson was flown to Germany, where doctors discovered a grapefruit-size abdominal abscess filled with Acinetobacter baumannii, a virulent bacterium resistant to nearly all antibiotics.

Found in the sands of the Middle East, the bacteria were blown into the wounds of American troops hit by roadside bombs during the Iraq War, earning the pathogen the nickname “Iraqibacter.”

“Veterans would get shrapnel in their legs and bodies from IED explosions and were medevaced home to convalesce,” Strathdee told CNN, referring to improvised explosive devices. “Unfortunately, they brought their superbug with them. Sadly, many of them survived the bomb blasts but died from this deadly bacterium.”

Today, Acinetobacter baumannii tops the World Health Organization’s list of dangerous pathogens for which new antibiotics are critically needed.

“It’s something of a bacterial kleptomaniac. It’s really good at stealing antimicrobial resistance genes from other bacteria,” Strathdee told Life Itself attendees. “I started to realize that my husband was a lot sicker than I thought and that modern medicine had run out of antibiotics to treat him.”

With the bacteria growing unchecked inside him, Patterson was soon medevaced to the couple’s hometown of San Diego, where he was a psychiatry professor and Strathdee was the associate dean of global health sciences at the University of California, San Diego.

“Tom was on a roller coaster – he’d get better for a few days, and then there would be a deterioration, and he would be very ill,” said Dr. Robert “Chip” Schooley, a leading infectious disease specialist at UC San Diego who was a longtime friend and colleague. As weeks turned into months, “Tom began developing multi-organ failure. He was sick enough that we could lose him any day.”

Searching for a needle in a haystack

After that reassuring hand squeeze from her husband, Strathdee sprang into action. Scouring the internet, she had already stumbled across a study by a Tbilisi, Georgia, researcher on the use of phages for treatment of drug-resistant bacteria.

A phone call later, Strathdee discovered phage treatment was well established in former Soviet bloc countries but had been discounted long ago as “fringe science” in the West.

“Phages are everywhere. There’s 10 million trillion trillion – that’s 10 to the power of 31 – phages that are thought to be on the planet,” Strathdee said. “They’re in soil, they’re in water, in our oceans and in our bodies, where they are the gatekeepers that keep our bacterial numbers in check. But you have to find the right phage to kill the bacterium that is causing the trouble.”

Buoyed by her newfound knowledge, Strathdee began reaching out to scientists who worked with phages: “I wrote cold emails to total strangers, begging them for help,” she said at Life Itself.

One stranger who quickly answered was Texas A&M University biochemist Ryland Young. He’s been working with phages for nearly 45 years.

“You know the word persuasive? There’s nobody as persuasive as Steffanie,” said Young, a professor of biochemistry and biophysics who runs the lab at the university’s Center for Phage Technology. “We just dropped everything. No exaggeration, people were literally working 24/7, screening 100 different environmental samples to find just a couple of new phages.”

‘No problem’

While the Texas lab burned the midnight oil, Schooley tried to obtain FDA approval for the injection of the phage cocktail into Patterson. Because phage therapy has not undergone clinical trials in the United States, each case of “compassionate use” required a good deal of documentation. It’s a process that can consume precious time.

But the woman who answered the phone at the FDA said, ” ‘No problem. This is what you need, and we can arrange that,’ ” Schooley recalled. “And then she tells me she has friends in the Navy that might be able to find some phages for us as well.”

In fact, the US Naval Medical Research Center had banks of phages gathered from seaports around the world. Scientists there began to hunt for a match, “and it wasn’t long before they found a few phages that appeared to be active against the bacterium,” Strathdee said.

Back in Texas, Young and his team had also gotten lucky. They found four promising phages that ravaged Patterson’s antibiotic-resistant bacteria in a test tube. Now the hard part began – figuring out how to separate the victorious phages from the soup of bacterial toxins left behind.

“You put one virus particle into a culture, you go home for lunch, and if you’re lucky, you come back to a big shaking, liquid mess of dead bacteria parts among billions and billions of the virus,” Young said. “You want to inject those virus particles into the human bloodstream, but you’re starting with bacterial goo that’s just horrible. You would not want that injected into your body.”

Purifying phage to be given intravenously was a process that no one had yet perfected in the US, Schooley said, “but both the Navy and Texas A&M got busy, and using different approaches figured out how to clean the phages to the point they could be given safely.”

More hurdles: Legal staff at Texas A&M expressed concern about future lawsuits. “I remember the lawyer saying to me, ‘Let me see if I get this straight. You want to send unapproved viruses from this lab to be injected into a person who will probably die.’ And I said, “Yeah, that’s about it,’ ” Young said.

“But Stephanie literally had speed dial numbers for the chancellor and all the people involved in human experimentation at UC San Diego. After she calls them, they basically called their counterparts at A&M, and suddenly they all began to work together,” Young added.

“It was like the parting of the Red Sea – all the paperwork and hesitation disappeared.”

‘It was just miraculous’

The purified cocktail from Young’s lab was the first to arrive in San Diego. Strathdee watched as doctors injected the Texas phages into the pus-filled abscesses in Patterson’s abdomen before settling down for the agonizing wait.

“We started with the abscesses because we didn’t know what would happen, and we didn’t want to kill him,” Schooley said. “We didn’t see any negative side effects; in fact, Tom seemed to be stabilizing a bit, so we continued the therapy every two hours.”

Two days later, the Navy cocktail arrived. Those phages were injected into Patterson’s bloodstream to tackle the bacteria that had spread to the rest of his body.

“We believe Tom was the first person to receive intravenous phage therapy to treat a systemic superbug infection in the US,” Strathdee told CNN.

“And three days later, Tom lifted his head off the pillow out of a deep coma and kissed his daughter’s hand. It was just miraculous.”

A legacy

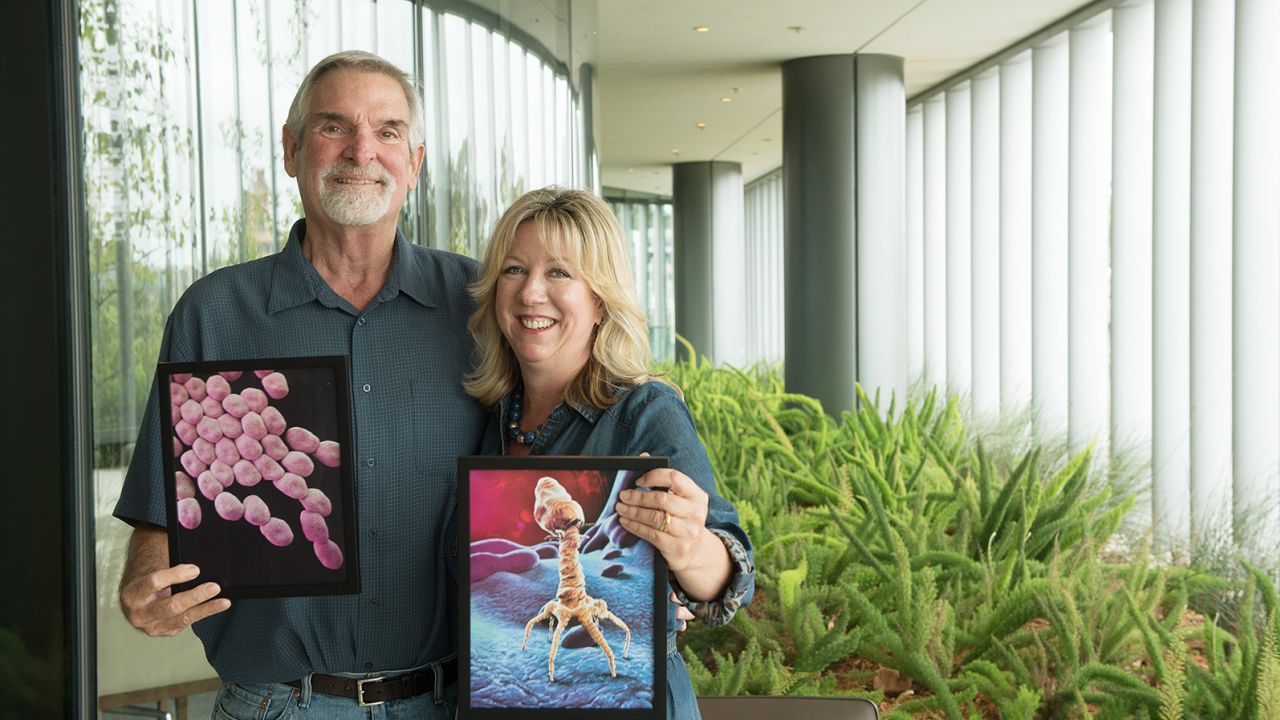

Today, more than six years later, Patterson is happily retired, walking 3 miles a day and gardening. The couple are back to traveling the world. But the long illness took its toll: Patterson was diagnosed with diabetes and is now insulin dependent, with mild heart damage, no feeling in the bottoms of his feet and gut damage that affects his diet.

“But we’re not complaining! I mean every day is a gift, right? People say, ‘Oh, my God, all the planets had to line up for this couple,’ and we know how lucky we are,” Strathdee said.

“We don’t think phages are ever going to entirely replace antibiotics, but they will be a good adjunct to antibiotics. And in fact, they can even make antibiotics work better,” she added.

“We feel like we need to tell our story so that other people can get this treatment more easily.”

To do so, the couple published a memoir: “The Perfect Predator: A Scientist’s Race to Save Her Husband From a Deadly Superbug.”

Strathdee and Schooley have opened the Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics, or IPATH, where they treat or counsel patients suffering from multidrug resistant infections. And Schooley will soon start clinical trials using phages on a deadly antibiotic-resistant bacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, that attack patients with cystic fibrosis.

Patterson’s case was published in the journal Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy in 2017, jump-starting new scientific interest in phage therapy.

“And there’s been many other labs that have joined in – Yale now has a phage therapy program, Baylor, Brussels … the Australians, Lyon, France, and more,” Strathdee told the Life Itself audience.

“What we need next is a phage library,” she continued. “We don’t want to have to go from bog to bedside every time we need phages, right? We want to be able to go to a walk-in cooler and source phages that are characterized and cataloged and personalize them for patients.”

Strathdee is quick to acknowledge the many people who helped save her husband’s life. But those who were along for the ride told CNN that she and Patterson made the difference – and continue to search for a solution to the growing superbug crisis.

“I think it was a historical accident that could have only happened to Steffanie and Tom,” Young said. “They were at UC San Diego, which is one of the premier universities in the country. They worked with a brilliant infectious disease doctor who said, ‘Yes,’ to phage therapy when most physicians would’ve said, ‘Hell, no, I won’t do that.’

“And then there is Steffanie’s passion and energy – it’s hard to explain until she’s focused it on you. It was like a spiderweb; she was in the middle and pulled on strings,” Young added. “It was just meant to be because of her, I think.”